Residents of the homeless shelter project on Benson Street in 86th Street, aside from the controversy over the “valid contract,” have shifted their focus to whether the stormwater engineering permits were legally applied for, becoming another crucial legal battleground for the Chinese community residents. Experts point out that this issue involves a new regulation passed by New York City in 2022, with broad implications that have even caused delays in several government-led projects.

Representatives of the residents have stated that the stormwater engineering issue will be raised as an important record and plan to formally explain it during a meeting with the community board later this month. The regulation stipulates that for development projects disturbing soil over 20,000 square feet or adding impervious area over 5,000 square feet, a stormwater engineering permit from the New York City Department of Environmental Protection must be obtained before development approval can proceed.

According to the regulation, the stormwater engineering permit cannot be exempted or delayed, and even the Department of Buildings (DOB) has no discretion in the matter. In contrast, there still exists an exemption mechanism for permits related to hotels or temporary hotels under the New York City Planning Commission (CPC), but stormwater engineering falls under mandatory thresholds and is viewed as having stricter procedural requirements.

It is understood that since the passage of this regulation during the pandemic, it has led to over a hundred government projects facing delays. The Department of Environmental Protection and the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) had jointly organized a workshop, where multiple architects responsible for government projects publicly expressed that the stormwater engineering review process is complex and time-consuming, becoming a major bottleneck in the development progress.

Regarding this particular case, residents pointed out that the controversial project is a new construction, and based on the blueprints, the added impervious area exceeds 7,000 square feet, clearly surpassing the legal threshold of 5,000 square feet, necessitating the application for a stormwater engineering permit by law. Even if the existing impervious area of the old building is higher, as long as the “added” area of the new construction exceeds the limit, a new application must be made. The Department of Environmental Protection has made it clear that “the reduced impervious area of the new building compared to the old building” cannot be used as a reason to exempt the application.

Residents also questioned whether the developer, when submitting the application to the Department of Buildings, falsely indicated “no” in the field of “whether the added impervious area exceeds 5,000 square feet,” while the content of the blueprints shows that the actual area exceeds the limit, potentially constituting procedural misrepresentation warranting further scrutiny.

In summary, stormwater engineering is not a technical issue but a threshold issue of “whether development can be legally conducted”; once the permit is not obtained, the entire project cannot proceed legally, rendering any related demolitions or subsequent construction meaningless.

Currently, the Board of Standards and Appeals (BSA) of New York City has officially docketed the case of 2501 86th Street in Brooklyn, making it a public case. Following the procedure, the BSA will proceed to collect written materials from all parties and schedule a public hearing once all documents are in order. During this period, any resident or professional with relevant background may submit written opinions and supporting materials, simply citing the BSA case number 2025-55-A. Chinese community residents express hope that through this open process, more professionals will be attracted to identify any regulatory and procedural loopholes that residents may have overlooked.

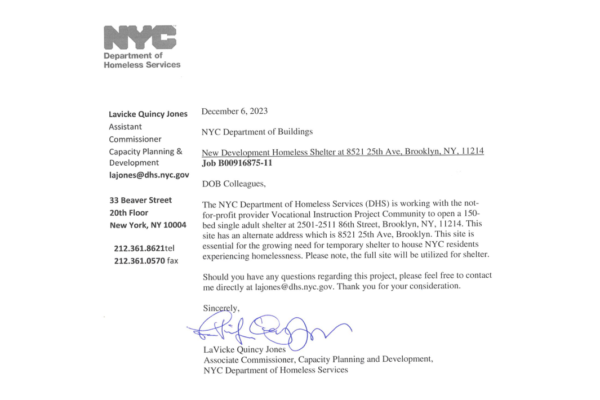

Prior to Mr. Ma and Alex, residents filing an appeal with the BSA, the Department of Buildings (DOB) rejected the residents’ appeal claims in December 2025. The 96 zoning challenges raised by residents were categorized by the DOB into five main types: 52 disputes related to the “valid contract,” 9 disputes concerning “short-term hotel (MDL definition),” 16 disputes on whether C8 commercial zones permit such use, 1 dispute related to the correlation between the valid contract and flood zones, and 18 miscellaneous complaints covering issues like inadequate enforcement, community opposition, and approval disputes unrelated to zoning.

The majority of the 52 disputes center around the existence of a legally valid city/state contract. The DOB believes that although the cooperation letter from the Department of Homeland Security is not a formal contract, it demonstrates that the signing process is underway, allowing for submission of confirmatory documents before issuing temporary or formal occupancy permits, thus allowing the project to continue.

Regarding whether having only 24 rooms in the project constitutes a short-term hotel, the DOB determined it as lawful based on zoning resolutions. It also noted that public temporary housing use can be set up in the C8 commercial zone under additional conditions without the need for special permissions.

Concerns raised by residents regarding flood zone flood prevention, fire safety, temporary occupancy permit durations, community opposition, surrounding environmental impacts, and enforcement fairness were deemed by the DOB to exceed the scope of zoning challenges review and were not included in substantive judgments.