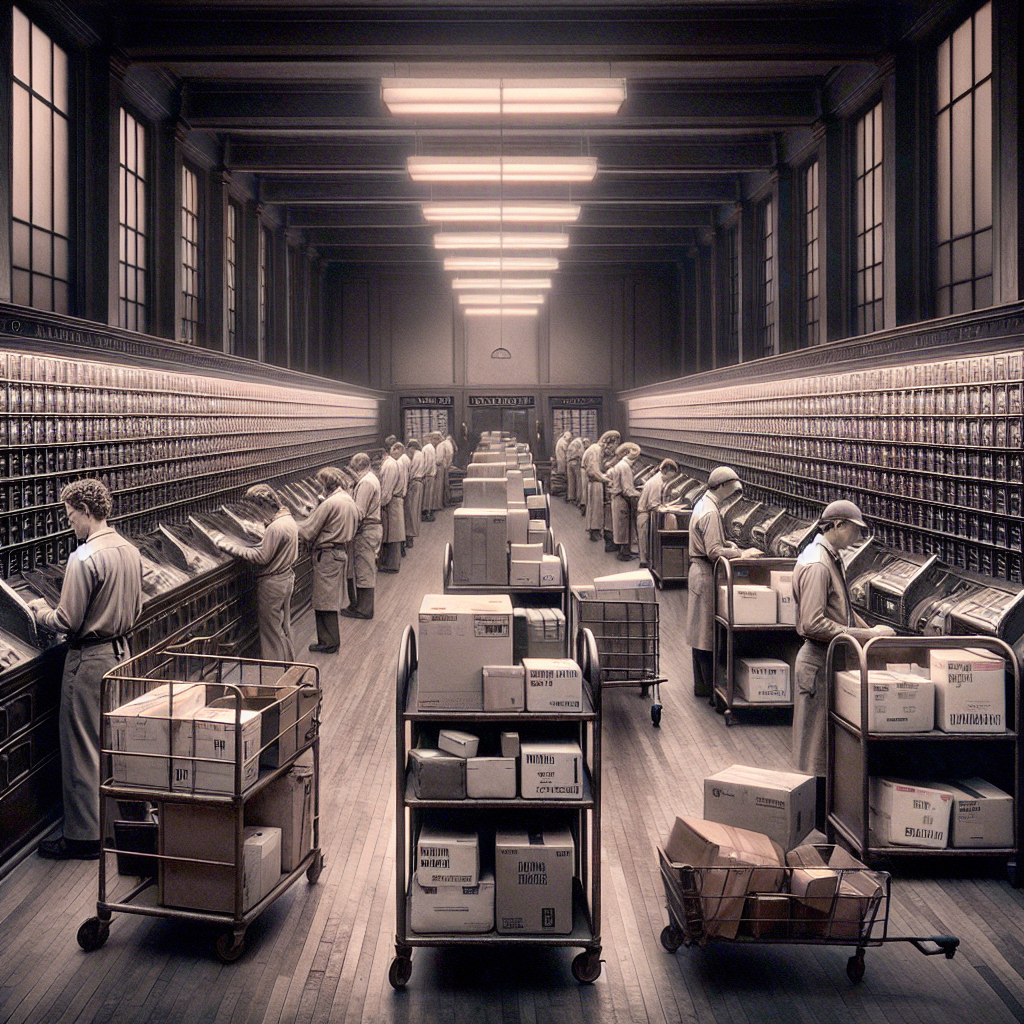

In the quiet morning of the post office, metal carts lined up against the walls, not filled with ordinary letters but with variously shaped parcels. Postal workers were busy sorting through the packages, with their scanners beeping as they scanned the barcodes.

If in the past the USPS was born to deliver letters, today it finds itself struggling in an awkward reality. The system originally designed for “equality for all” is now facing an inevitable issue: when business types and service costs undergo significant changes, can the promise of “equality” still be upheld?

For USPS, this is not a multiple-choice question.

In the discussion of the “Universal Service Obligation” and the concept of uniform postage in the creation of USPS, it is the core institutional foundation: regardless of distance or population size, every individual should have access to the same delivery service. The intention of this design is crystal clear – it turns the legal concept of “equality” into an operational daily practice. A simple stamp can bridge the gap between wealth disparities, while a delivery network spanning the nation connects bustling cities to remote areas.

And it is the intertwining of the weight of this mission and the changes in the modern postal industry that firmly entangle USPS. With the advancement of electronic communication, the volume of traditional mail has sharply declined. This business, once the cornerstone of USPS revenue due to its high delivery density, lowest operating costs, and stable income, now faces a challenge. The funds used by USPS to offset the cost losses incurred in remote areas and low-density routes mostly derived from this revenue stream.

Compared to traditional mail, the new parcel delivery requires high costs in manpower, time, and transportation. For most commercial logistics companies, adjusting parcel delivery pricing in real-time based on business conditions and optimizing non-profitable delivery areas and routes can solve the issue. However, for USPS, such trades-offs do not exist. Services cannot be “chosen,” whether it is a sparsely delivered rural road or a bustling neighborhood with repeated deliveries to high-end apartments.

Since optimizing remote areas and routes is not an option, the only solution is to adjust prices. However, for the same reasons, USPS cannot arbitrarily adjust sending prices. Because USPS is not a private company but exists as a national infrastructure, the services provided represent the nation’s public service. Therefore, the “price” of this service cannot be measured solely by financial indicators. The difficulty in USPS operation stems from: being required to operate like a market entity, while also bearing the responsibility of the nation’s postal service.

Therefore, any fundamental institutional changes involving USPS do not only stem from USPS internal decisions but require authorization at the legislative level before enforcement. Because public services must withstand public scrutiny and procedural examination.

Therefore, USPS is not unable to adjust prices but must submit applications to the Postal Regulatory Commission (PRC) within the “framework set by congressional legislation.” PRC reviews USPS’s proposed rate increases based on the principles of “reasonable, transparent, non-discriminatory.” Congress only makes decisions at the institutional level, such as whether to allow differential pricing, which mail types belong to the “market competitive” category, and which belong to the “products requiring universal service,” etc.

In reality, USPS adjusts postage rates almost every one to two years. However, the extent of the increase is strictly controlled: in principle, the majority of core postage rates cannot exceed the inflation rate of that year. Even with rapidly rising delivery costs, increasing item diversity, and weights surpassing traditional mail, these reasons cannot be grounds for significantly raising postage. For example, First-Class Mail, well-known to many, has seen adjustments over decades in a “slow, small, step-by-step” manner.

In this structural contradiction, the tension between “efficiency” and “equality” often cannot be easily resolved. As delivery volumes continue to rise and service paces quicken, the system itself does not self-resolve these issues. The pressure that arises gradually infiltrates into every daily route and each delivery due to these changes. The promise of “equality” is slowly being fulfilled under this pressure.

From an operational perspective, USPS does not differ fundamentally from any large logistics company: sorting centers, transport nodes, route planning, and finally, delivery form an incessant network. The difference lies in what the USPS network carries; more than just the flow of goods.

From bustling cities to remote areas, USPS must maintain a high level of accessibility amid this imbalance. This consistency is not a result of business optimization but is a deliberately maintained state required by the institution. Regardless of delivery volume or distance, this service network must exist in its entirety and operate normally every day. As a result, this network leans more towards being an infrastructure rather than a business system that expands and contracts with demand.

For most users, this institutional design often remains invisible. A bill, a document, a package, once delivered, exits from view. When the network operates smoothly, its public nature is often overlooked, everything seems natural; however, disruptions such as delays, backlogs, or route adjustments, quickly spread across various facets of daily life.

This is the peculiarity of USPS: it sustains not a singular commercial system but a highly decentralized, interdependent social operation model. Any adjustments to the postal network would affect the accessibility of public services in different regions.

At the same time, USPS is still constrained by efficiency. Apart from institutional responsibilities, it also faces practical issues such as organizational development and employee livelihood. Many of these actual conflicts and pressures fall on frontline staff, especially community letter carriers like Bob.

Regardless of how the system is designed or how far the network extends, postal services must be completed at very specific addresses. This distance is often short but the most challenging to standardize. From the post office to the doorstep, from the mailbox to the residence, it forms the so-called “last mile.”

In this segment of the journey, efficiency indicators translate into increased workload and higher deadline requirements. Every route adjustment, mail volume increase, and service pace acceleration directly impact the shoulders of the letter carriers. Each change means more walking distance, real-time decision-making, and higher risk of errors.

Unlike the front-end automation of intelligent sorting systems, the last mile operation still heavily relies on human labor. Access control, mailbox labeling clarity, frequent address changes, etc., cannot be preincorporated into process design but directly affect the stability of deliveries. Delivery completion time, scanning points, route performance become benchmarks for measuring work.

USPS must respond to the realities of efficiency and cost requirements while not abandoning the commitment to “equal delivery.” It carries both the expectations of market-oriented services and the role of national infrastructure. This dual positioning keeps USPS in a state of constant adjustment and rebalancing. Each address, each knock on the door, become processes that shape this dual commitment. And the last mile becomes the focal point enduring this tension.

It is because of this, that the existence of USPS itself becomes an abbreviation of an institutional pledge: transforming abstract public commitments into the everyday that is often taken for granted. Beneath this continual and stable operation, a country’s understanding of equality and public services quietly inscribes itself into everyone’s lives. ◇

For further reading:

The abbreviation of equality in the US postal service system (part 1)