On December 30th, the ongoing coverage of the issue of missing cultural relics in the Nanjing Museum by the “Asian Weekly” was silenced on Weibo and WeChat, sparking public outcry. The topic labeled “Asian Weekly’s Weibo being censored” momentarily surged to second place in Weibo’s hot search trends, but later disappeared completely from the hot search list.

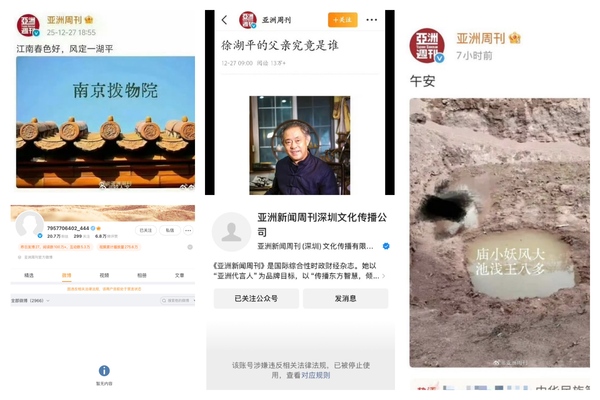

The Weibo account of “Asian Weekly”, which had 207,000 followers, had its name changed to a string of numbers on December 30th. All the content on the Weibo account was cleared, and the account page displayed a message stating, “Due to violations of relevant laws and regulations, this user is currently under gag order,” with no trace of the account accessible through Weibo’s search function.

The censorship of “Asian Weekly” has stirred up a tsunami of public opinion.

Netizens commented, “Honestly, the fact that this topic trended shows that the censorship on Weibo was a desperate move.” “This should lead to a permanent ban.” “No media reported on the Nanjing Museum issue, but when they did, they got banned.” Some expressed surprise at the swift and thorough action taken.

“Ridiculous rule of law.” “Silence that deafens.” “Pitch black.” “Water can carry a boat, but also capsize it.” “Cannot shut down the voices of the people, nor can you silence their hearts.” “Rare to see such a clear one-sided action.”

“This Nanjing Museum issue has a big impact.” “Xu (referring to former director of the Nanjing Museum, Xu Huping) isn’t scary, but the people behind him are extremely powerful.” “The big shots have intervened.” “Seems like the Nanjing Museum incident will be swept under the rug.” “Will it just end like this, with a dramatic conclusion?”

“A sigh! Cannot let you know the truth! Once you know the truth, how can we make you obey? How can we make you willingly hand over your treasures for them to profit?” “Suddenly thinking about our investigative journalists, political journalists, and social news reporters of the past, why have they all suddenly disappeared?”

Some netizens revealed, “Not just Weibo, all accounts across the web are gone.” “WeChat public accounts are also gone, a complete purge, so how many cultural relics have gone missing in Nanjing, just in Nanjing? Why the fear?”

The author of a headline article and Weibo influencer “Sugar Cat from Old Trafford” commented, “After reading some of their (referring to “Asian Weekly”) Weibo posts, it was evident they were close to being banned. Now the account is just a string of numbers, first time seeing a verified account get banned.”

The CEO of Zhuhai Hengqin Huajun Bamboo Media Co., and Weibo influencer “Bamboo of Huajun’s Weibo” stated, “Recently, ‘Asian Weekly’ gained popularity, but no mainland media covered it, why? They all know, even if they have to expose the dark side, it must be about foreign matters. For instance, the recent trendy topic about ‘Decapitation Line,’ it has traffic and appeal.”

Famed Chinese critic, writer, and football journalist Li Chengpeng posted on the social media platform X, “The ‘Asian Weekly’ reporting on the Nanjing Museum incident has been shut down. The investigative reports by ‘Asian Weekly’ were first forced to be deleted, and after a cryptic poem hinting at ‘unreturned painted scenes of spring,’ the account turned into a string of numbers before being shut down completely.”

“‘Asian Weekly’ does have certain background support, but being completely shut down, shows how deep the waters run. The gatekeepers are as deep as the sea.”

On December 17th, mainland media “The Paper” exclusively published an article titled “Why did the Ming Dynasty painting ‘Spring in Jiangnan’ from the Nanjing Museum appear in the auction market?” which put the Nanjing Museum in the spotlight. Subsequently, “Asian Weekly” continued to track and report on a myriad of issues related to the loss of cultural relics from the Nanjing Museum, including the following contents.

On the evening of December 23rd, “Asian Weekly” uploaded a video of over a minute on its official Weibo account, explaining, “What the former director’s (referring to former director of the Nanjing Museum, Xu Huping) neighbor said.” The video showed that on December 22nd from 10 pm to noon on the 23rd, the police surrounded Xu Huping’s villa for over ten hours before taking Xu Huping, his wife, and maid away.

On December 25th, “Asian Weekly” shared a meaningful image that depicted “Nanjing Museum” as “Nanjing Displacement Museum,” and on the 27th, it reposted the image with the caption “The beauty of spring in Jiangnan, with the wind calm over a serene lake,” seemingly insinuating Xu Huping’s role in the loss of cultural relics.

On December 26th, “Asian Weekly” stated that Nanjing’s Yilan Studio confirmed they owned the painting ‘Spring in Jiangnan’ by Qiu Ying no later than 2000. Upon verification, it was found that in the middle color pages of the eighth issue of “Reader Magazine” in 2000, the content was featured, with Yilan Studio advertising in each issue from the first to the twelfth every page throughout the year.

This contradicts the Nanjing Museum’s claim that ‘Spring in Jiangnan’ was sold only in 2001. “Asian Weekly” urged netizens to search for clues if Yilan Studio also placed such advertisements in “Reader Magazine” around 2000 and advised art experts to carefully examine whether the paintings published by Yilan Studio had been lost from other collection places.

On December 27th, “Asian Weekly” posted an article titled “Who is Xu Huping’s father exactly” reporting that Xu Huping’s father had once held the rank of deputy bureau chief, with comrades widespread in Jiangsu Province. The article spread widely online but was quickly deleted and labeled as “harmful information.”

Shortly after the deletion of the post, “Asian Weekly” greeted with a “good afternoon” on their Weibo account and uploaded a picture with the caption “In a tiny temple, evil spirits run rampant, in a shallow pond, turtles abound.”