On December 25, 2025, the Nanjing Museum’s Ming Dynasty painting “Spring in Jiangnan” surfaced in the auction market, triggering a whistleblower report from a retired employee accusing the former museum director, Xu Huping, of large-scale theft and smuggling of cultural relics. Recently, Xu Huping and his wife were taken away by the police from their villa. Experts pointed out that this case has exposed the deep-rooted problems of “privatizing public resources” and “rent-seeking of power” in the cultural and museum system, reflecting the encroachment of public cultural resources by those in power.

On the evening of December 23, Hong Kong’s “Asian Weekly” released a video showing a police raid on Xu Huping’s villa at around 10 p.m. on the 22nd, which continued until around noon on the 23rd when Xu Huping, his wife, and their maid were taken away.

According to Xu Huping’s neighbor, the night before the incident, their house was brightly lit all night, which was unusual. A large number of police officers arrived and surrounded the villa, and several official vehicles entered the premises the following day, taking away the individuals involved.

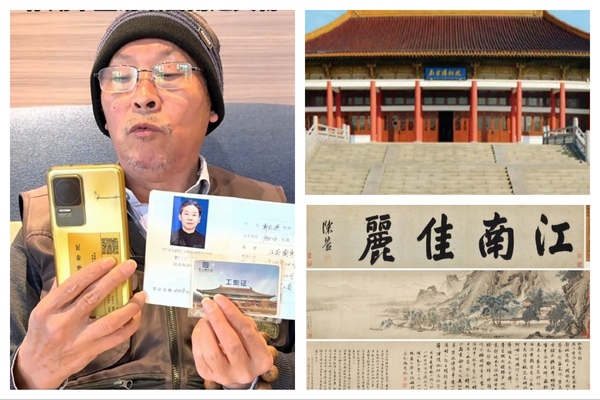

Retired employee of the Nanjing Museum, Guo Lidian, made a public report on December 21 through a video platform accusing Xu Huping of extensive theft and smuggling of cultural relics from the Forbidden City during his tenure.

The report alleged that Xu Huping illegally removed a large number of valuable cultural relics by tearing off sealing labels without approval from the National Cultural Heritage Administration, instructed experts to authenticate genuine artifacts as “forgeries,” sold them at low prices, and further profited from reselling them through an auction company opened by his son in Shanghai.

The report also indicated that Xu Huping gifted several paintings to officials, including the Chief Prosecutor and Anti-Corruption Bureau Director of Jiangsu Province.

The incident originated from the appearance of the Nanjing Museum’s Ming Dynasty painting “Spring in Jiangnan” in the auction market. In 1959, descendants of the renowned collector Pang Laichen donated 137 precious ancient paintings and calligraphy pieces to the Nanjing Museum, including the national first-grade cultural relic “Spring in Jiangnan.”

In late June 2025, Pang Laichen’s great-granddaughter, Pang Shureng, discovered during a court-mediated inspection in the Nanjing Museum’s warehouse that 5 pieces of the collection were missing, including “Spring in Jiangnan” as well as four other works such as Zhao Guangfu’s “Double Horse Painting.”

Shocking revelations followed as “Spring in Jiangnan” appeared in a spring auction catalogue in Beijing with a starting price of a staggering 88 million yuan (RMB).

The Nanjing Museum stated in written replies that the 5 paintings had been identified as “fakes” by expert panels in 1961 and 1964, and had undergone “adjustments and transfers” in the 1990s. Pang Shureng questioned, “My great grandfather Pang Laichen’s collection is widely acknowledged. Even with academic debates, why weren’t the donors informed? The handling procedures lacked transparency in terms of where they were transferred to.”

Further investigations revealed that “Double Horse Painting” was sold for 2.3 million yuan at an auction in Shanghai in June 2014. The appearance of a painting deemed a “fake” by the Nanjing Museum on the auction market raised public concerns.

Zhang Junjie, a history student at San Antonio Mountain Community College in the United States, emphasized that even if artifacts are identified as forgeries, museums should prioritize returning them to donors rather than disposing of them without authorization. He stated, “The purpose of the donation is to serve the public and allow more citizens to understand Chinese culture. It is a public, non-profit donation. The museum, however, is treating it as a profit-making opportunity, which goes against the original intention of the donation.”

Zhang Junjie’s systemic analysis identified the essence of this issue as “unrestricted power.” He believed that the fundamental problem lies in the misalignment of power and culture relationships, where rulers view relics, culture, and even the nation as tools for governance. Just as during the Cultural Revolution when traditional culture was destroyed in the name of “destroying the old,” the current emphasis on cultural preservation for national rejuvenation still instrumentalizes relics; it is all about power. Zhang highlighted historical instances, like Kang Sheng, a former national leader, who seized treasures from intellectuals during the Cultural Revolution.

Wu Shaoping, head of the Overseas Human Rights Lawyers Alliance, analyzed that this case epitomizes “privatizing gains under the guise of public service,” with a complete chain of operations: authentic items are devalued as forgeries in the evaluation process, sold at low prices, and then re-enter the auction market at inflated prices, effectively transforming power into money.

Wu Shaoping further pointed out that cultural relic transactions might involve deeper money laundering and bribery schemes. Pricing of relics often involves additional factors, and bribers can disguise illicit funds as legitimate transactions through high-value bidding at auctions, effectively laundering money.

In his video report, Guo Lidian disclosed that since 2008, over 40 Nanjing Museum employees had collectively reported misconduct. Xu Huping’s corruption materials were even published by Xinhua Internal Reference, but were left unresolved due to the involvement of too many bribe recipients and powerful forces behind them. Guo had reported to multiple departments since 2010 but had not received any effective feedback.

On December 24, “Asian Weekly” revealed that Guo Lidian had been receiving threatening phone calls. When questioned by various parties, the National Cultural Heritage Administration, Jiangsu Provincial Discipline Inspection Commission, and Department of Culture and Tourism either claimed to be “verifying the allegations,” suggested to “contact other departments,” or left the phone unanswered, showing a clear stance of evasion.

Wu Shaoping contextualized the phenomenon within a broader backdrop of systemic corruption. He pointed out that from the mismanagement of donations in the Red Cross and charity associations to fires at granaries and loss of state-owned enterprise assets, to organ trafficking, “as long as it involves so-called state-owned or public assets, officials at all levels will use various means to convert them into their own.”

He highlighted the powerless position of museums within the Chinese system, which are dependent on officials at various levels. When higher-ups want to take relics, museums are powerless to resist. If corrupt officials become museum directors, they use relics as a platform for personal advancement. This structural issue is intimately tied to rent-seeking behavior.

Zhang Junjie concurred, stating that whether it’s political corruption, sports scandals, or educational malpractice, similar issues have surfaced across all sectors. Museum directors leveraging their positions for relic adjustment mirrors the rent-seeking practices seen during the era of the one-child policy—it’s all about power-seeking.

Wu Shaoping concluded, “With each lesson taught by the Chinese Communist Party, more and more people are becoming aware. The number of people willing to hand over relics to the CCP is decreasing.” He emphasized the systemic encroachment of public power into private property, noting that the CCP’s dictates on relics render them state property to be possessed; anyone who refuses is deemed illegal. By employing power, they blatantly seize control, manipulating both judicial and artifact appraisals to suit their agenda.

Zhang Junjie highlighted a profound paradox from a cultural preservation perspective, where recent online narratives emphasized the looting by the British Museum of Chinese relics, stoking nationalism. However, the events at the Nanjing Museum reveal the destruction of Chinese relics in Chinese hands, contrasting with the British Museum’s superior preservation practices—an example of bankruptcy in nationalist propaganda. He summarized that true nationalism beneficial to national development requires separating state and political power, safeguarding national culture and property by ensuring they are shielded from power erosion and control.