Recently, the Nanjing Museum has been rocked by news of suspected theft and selling of its cultural relics. As the investigation progresses, in addition to official verification progress, social media platforms have also seen a large amount of disclosure of details related to the case, alleging that the number and time span of the relics involved far exceed what was previously known to the public.

Multiple investigation leads indicate that in 1997, under the leadership of former director Xu Huping, the Nanjing Museum once removed 1,259 items from its collection catalog in one go, and allocated them as a whole to the Jiangsu Provincial Cultural Relics Store, which was then under Xu Huping’s supervision. The authentication basis of the related collections, the approval process, and their subsequent whereabouts have become the focal points of the current investigation.

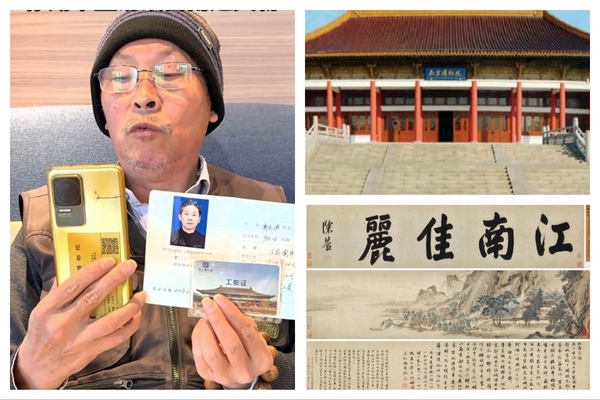

The case was initially reported by the descendants of a collector from the late Qing Dynasty to the early Republican era, Pang Laichen. In May of last year, the descendants of the Pang family discovered that a scroll of a painting by Ming Dynasty artist Qiu Ying, donated by the family to the Nanjing Museum in 1959, had appeared in a Beijing auction market with an estimated pre-sale value of up to 88 million yuan. Subsequently, the Pang family members reported to the relevant authorities, questioning the specific process by which the relic had left the museum system and entered the market.

Nanjing artist Zeng Chao (pseudonym) told Dajiyuan that Xu Huping had long held important resources within the Jiangsu cultural relics system and had significant power over the authentication, allocation, and disposal processes of cultural relics during his tenure. He said, “Xu Huping’s affairs are widely circulated among us privately, and it is widely believed within the circle that members of his family also participated in the transfer of related cultural relics. What is authentic and what is fake in the museum is often not simply an academic issue, but intertwined with the interests of experts.”

Zeng Chao pointed out that for a considerable period of time in the past, some cultural relics identified as “fake” or “lacking collection value” had left the museum system and entered the market, which was not an isolated case within the industry. He said, “It is difficult for the public to know how a relic is classified and how it is handled, leaving a considerable gray area.”

After the public report by the Pang family, a retired employee of the Nanjing Museum also reported Xu Huping by name, accusing him of transferring some of the museum’s cultural relics out of the museum system through the authentication and allocation procedures during his tenure. The report materials stated that some collections had been identified as “fake” at the time and had deviated from the museum’s collection, raising doubts about the authentication conclusions and related operational processes.

Zeng Chao stated that in the 1990s, the Nanjing Museum system had relatively loose regulations regarding the inventory, authentication, and circulation of cultural relics, with several key steps lacking public records and external supervision. He said, “Opacity creates opportunities for corruption. As long as a handling is done in the catalog, there is basically no one tracking the subsequent flow. Some take advantage of these gaps to claim the relics for themselves, making China’s museum system more like a black hole.”

In addition to official reports, social media users disclosed that investigators seized a total of 110 pieces of cultural relics in two separate raids at Xu Huping’s villa in Fugui Mountain, Nanjing, including some important relics believed to have been lost overseas; and more than 20 pending-to-be-traded relics were found in a warehouse associated with his son Xu Xiangjiang’s company. It was revealed that some relics were thought to be related to the relics relocated to the Forbidden City, with the components being mutually corroborative.

The disclosures also indicated that the accounting records obtained by investigators spanned from 1992 to 2024, showing that the illicit selling of related cultural relics had been ongoing for about 32 years, with buyers scattered domestically and internationally, and a single transaction reaching up to 32 million yuan. One of the relics, a Ru kiln sky-blue glaze vase from the Song Dynasty, was marked as “damaged and destroyed” in the internal records of the Nanjing Museum. The accuracy of these claims has not yet been officially confirmed.

Fujian scholar Wang Wenfang (pseudonym), when interviewed, stated that the attention triggered by the details disclosed on social media was not on the specific numbers themselves but on the issues of management and responsibility they pointed to. He said, “These claims have not yet been publicly explained by the authorities, but they did not appear out of thin air. They are pointing to a long-standing reality—once a relic strays from the museum system, it is almost impossible for the outside world to trace its complete trajectory.”

The exposure of the suspected theft and sale of cultural relics in the Nanjing Museum has sparked discussions on mainland Chinese social media platforms. Some netizens have compared this event to the modern history of Chinese cultural preservation. One netizen commented, “In 1949, the Kuomintang retreated to Taiwan, taking a large number of cultural relics from the mainland, which are now preserved in the Taipei Palace Museum without any losses. This is the true advantage of the system.” Others wrote, “Take them away, leaving them will only waste them” and “Thank you, Chiang Kai-shek, but unfortunately not all were taken away.”

The precursor of the Nanjing Museum was the National Central Museum established by educator Cai Yuanpei, proposed and founded by the National Government in 1933. In the 1930s, due to frequent warfare, a large number of Palace Museum relics were moved to Nanjing and briefly stored there. Some relics were later transported to Taiwan, some were returned to Beijing in the 1950s, and some remained in Nanjing.