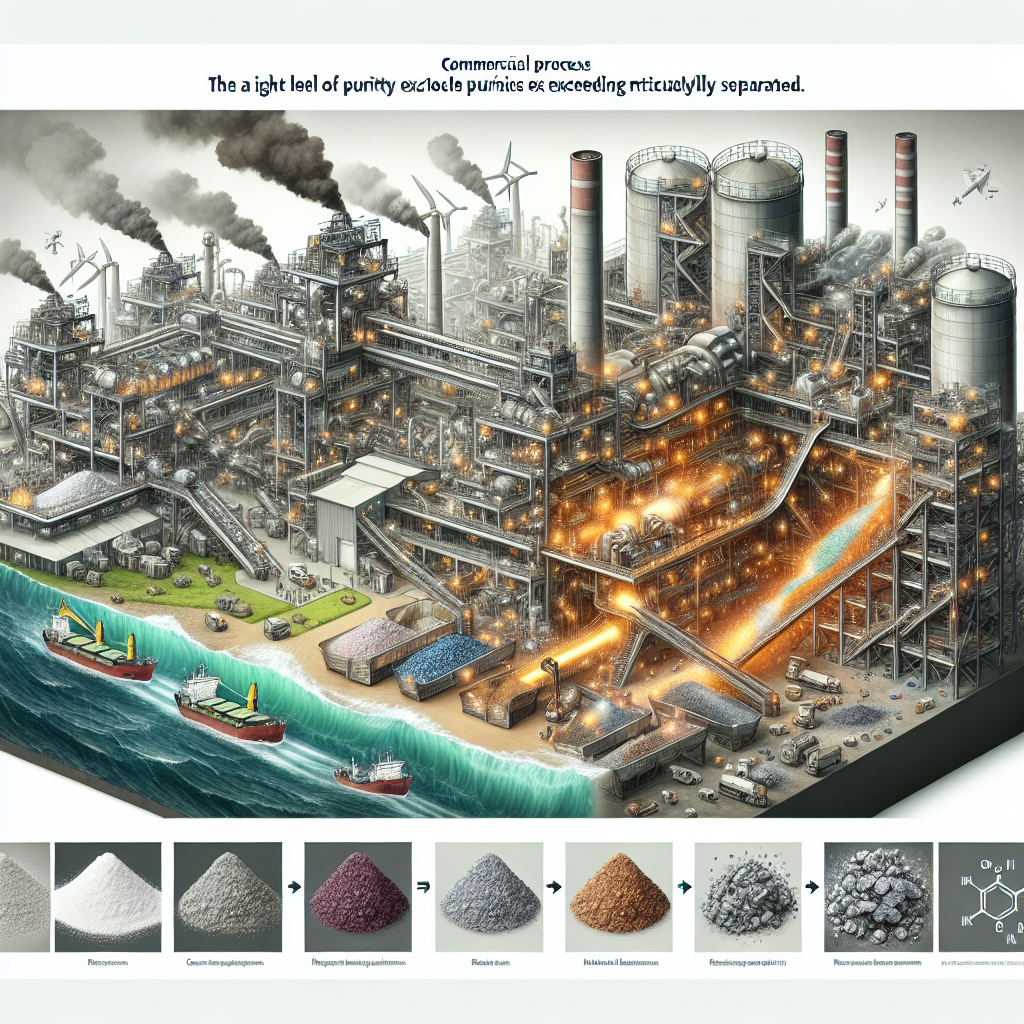

Rare earth elements, collectively known as the “industrial vitamins” of the 17 chemical elements, are essential for the commercial separation process. This involves extracting nearly similar rare earth elements from mineral ores in large-scale industrial production, with purity levels exceeding 99.9%. However, rare earth elements have transcended the scope of industrial raw materials, completely reshaping the global geopolitical landscape. Washington and Beijing are vigorously restructuring and cutting off the supply chains of rare earths, marking a strategic contest that encompasses future military, technological, and even economic dominance.

On November 11th, a exclusive report by The Wall Street Journal provided significant insights. While on the surface, the Chinese government fulfilled the “trade truce” agreement reached with the Trump administration by announcing a one-year suspension of implementing the latest round of rare earth export controls, the devil lies in the details.

China is brewing a new system known as “Validated End-User” (VEU), designed to precisely sever the channels through which the U.S. military obtains rare earth magnets from China. The insidiousness of this scheme is evident.

Firstly, Beijing, under the facade of “compliance with commitments and upholding free trade,” expedited export approvals for other civilian companies to meet President Trump’s demand for “relaxing controls.” This move was aimed at saving face in the international community.

Secondly, through the VEU system, China can openly use the pretext of “end-use control” to directly exclude companies associated with the U.S. military industrial complex from the rare earth supply list. It is crucial to note that rare earth magnets are core components of key military equipment such as fighter jets, submarines, and attack drones, serving as a “stranglehold” on U.S. national security and military superiority.

China’s actions not only undermine the basic trust of international trade but also once again demonstrate to the world that under an authoritarian regime lacking independent judiciary and free markets, commercial interests will always defer to political power. Any company reliant on China’s supply chain must be prepared to become a pawn in political games.

Facing China’s “plan,” Washington’s response transcends mere verbal condemnations and extends to substantial industrial and investment layouts.

Recently, U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s visit to eVAC company in Sumter, South Carolina, to celebrate the “first rare earth magnet manufactured in the U.S. in 25 years,” marks a significant moment in this “rare earth war.”

“This is the first rare earth magnet produced in the U.S. in 25 years,” Bessent enthusiastically told Fox Business News, “We are ending Beijing’s stranglehold on our supply chain.”

This is not just a magnet; it signifies the U.S.’s formal breakout from China’s “stranglehold.” It sends a crucial message that America’s industrial reshoring and supply chain restructuring are transitioning from blueprints to reality. The strategic value of rare earth magnets is self-evident. Bessent ties this to “national and economic security,” predicting the sustained “takeoff” of American manufacturing in 2026 and 2027, rooted in the actual reshaping of production capacity.

If manufacturing rare earth magnets represents a breakthrough “downstream,” investment in Africa is a strategic move “upstream.”

The latest data from Johns Hopkins University’s China-Africa Research Initiative shows that U.S. investment in Africa in 2023 reached $7.79 billion, nearly double that of China ($3.96 billion). This marks America’s return as the largest foreign direct investment (FDI) player in Africa since 2012.

Through this investment, the U.S. directly engages in the extraction and supply of crucial minerals like lithium, rare earths, cobalt, and tungsten in Africa. In essence, the U.S. is chipping away at China’s backyard operations in a more finance and compliance-centric manner, steering away from debt trap-driven initiatives like simple infrastructure development. This move aims to not just secure resources but also reshape a critical minerals supply chain independent of China’s control and more friendly.

The battlefield of the U.S.-China rare earth game expands beyond the two nations into a “coalition confrontation.” America understands that breaking China’s monopoly requires leveraging the power of allies. Key mineral agreements signed between the U.S. and allies like Japan and Australia embody this strategic approach.

Japan, a country that does not produce rare earths itself, is a vital partner in America’s rare earth strategy. This is due to its establishment of the “national strategic combo” over a decade ago. In response to China’s rare earth embargo crisis in 2010, Japan devised a national strategy centered on “diversifying supply sources, developing alternative technologies, strategic reserves, and resource recycling.”

Japan’s rare earth recycling technology and alternative material development have reduced its rare earth consumption by half, cutting its dependence on China from 90% to approximately 60%. By investing in the Australian company Lynas through Japan-Australia Rare Earths (JARE), Japan secures around 30% of its light rare earth supply domestically.

Japan’s greatest potential lies in its deep-sea rare earth mud. These mud deposits near the Minami-Torishima Islands have rare earth concentrations 20 times higher than China’s rare earth mines. Japan is not just a partner in U.S. technology and supply chain security but also likely to become a new rare earth supply hub in the future.

Hence, the U.S.-Japan rare earth agreement emphasizes Japan’s technological advantages, crisis management capabilities, and future potential. This move aims at “ensuring allies’ technological and strategic advantages” and jointly constructing a global rare earth security system.

The U.S. has signed an $85 billion critical minerals agreement with Australia, a direct “resource binding” pact. Australia boasts rich rare earth resources and mines, serving as a reliable partner who can provide operational supply in the short term.

The layout of this “Rare Earth NATO” indicates America’s efforts to establish a decentralized rare earth supply chain involving resource countries (like Australia, select African nations), tech countries (like Japan), and consumer countries (the U.S. and the EU), substantially weakening China’s strategic pricing power and diplomatic manipulation in the rare earth sector.

Reflecting on this rare earth game, it illustrates an increasingly ideological global economy. China’s attempt to achieve its political suppression and military goals through economic manipulation of rare earths is playing with fire. Weaponizing trade and involving civilian enterprises in geopolitical conflicts will only expedite the “derisking” of global industrial chains, and even prompt a direct “de-Chinification of communism.”

For the future, the author predicts that among the 500 major industrial products, China leads globally in production of over 220, signifying a long and arduous struggle between China and the U.S. in critical military and technological domains.

For the U.S., the themes of supply chain localization and alliance system construction will dominate investments in the coming years. While initially entailing higher costs, in the long run, this will ensure national and economic security.

For China, the efficacy of its rare earth leverage will diminish marginally. Once the global supply chain begins to pivot, it’s challenging to revert. In the future, China will not only confront the U.S. on the international market but also face rejection from a more diverse, resilient competitive supply chain system collectively built by Japan, Australia, Africa, and the EU.