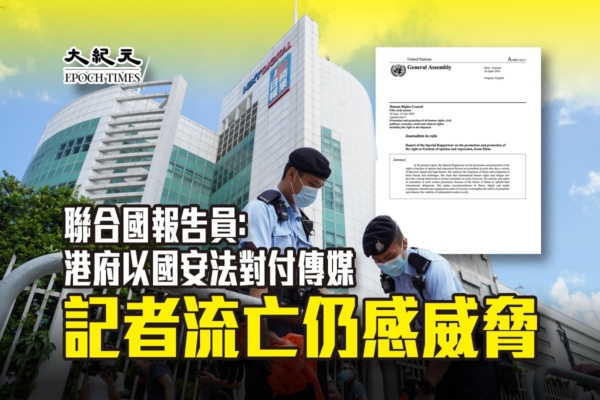

Since the enactment of the National Security Law in 2020, press freedom in Hong Kong has significantly deteriorated, with multiple independent media organizations forced to shut down and individuals facing charges under the National Security Law and incitement offenses. Irene Khan, a special rapporteur for the United Nations, recently submitted a report to the UN Human Rights Council on the global situation of exiled journalists, criticizing the Hong Kong government for using the National Security Law and Article 23 of the Basic Law to target the media, leading to journalists being imprisoned, silenced, or forced into exile.

The UN Human Rights Council held its 56th session from June 18 to July 12 this year, with one agenda item focused on “Promoting and protecting all human rights – civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights, including the right to development.” Irene Khan authored a report on the global situation of exiled journalists, which was presented during the session.

The English version of the report spans 19 pages, addressing the phenomenon of journalists going into exile globally, including in Afghanistan, China, Ethiopia, Myanmar, Russia, and other countries. The report highlights that while journalists in exile are not a new phenomenon, the situation has become increasingly severe in recent years. With online media providing more opportunities for journalists when their human rights and freedom of expression are threatened in their home countries, they can continue working abroad to disseminate information and criticize those in power.

The report emphasizes Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which clearly states that everyone has the right to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers. It also affirms the right of exiled journalists to seek, receive, and share information, ideas, and images without hindrance or restriction. Countries not only have an obligation to refrain from imposing arbitrary restrictions but also to legislate and regulate in accordance with international human rights standards allowing journalists to work safely and unhindered. This applies to all journalists, whether domestic or foreign.

Moving onto the report’s criticism of the Hong Kong government’s treatment of independent journalists, Irene Khan cited the use of vague laws related to “national security,” “counter-terrorism,” “criminal defamation,” or “fake news” by some countries to investigate, prosecute, and punish journalists. She mentioned Hong Kong’s National Security Law and Article 23 of the Basic Law, the Security Law Enforcement Regulations with broadly defined offenses such as “secession,” “subversion,” “terrorism,” and “collusion with foreign forces,” which also have extraterritorial effect.

She criticized the overly broad definition of offenses under these laws, which has led to implications for Hong Kong organizations and individuals’ cooperation with international entities such as the UN human rights system. Moreover, she noted that the Hong Kong government has extensively used these laws to target independent journalists and media, resulting in many being imprisoned, silenced, or fleeing abroad. Even many exiled journalists need to practice self-censorship, hindering their connections and collaborations with Hong Kong.

The report further highlighted the challenges faced by exiled journalists in maintaining their journalistic practices while in exile, using Hong Kong as an example. While most journalists leave their countries to continue working, many of them do not continue in journalism after relocating abroad. The report cited a survey by the International Federation of Journalists indicating that two-thirds of interviewed Hong Kong journalists had left the media industry after moving overseas. The same paragraph also referenced surveys showing a similar situation for exiled journalists from Afghanistan, Belarus, and Russia.

Regarding the reasons for exiled journalists leaving the media industry, the report explains that they may lack personal safety concerns, fear retaliation against their families back home, lack familiarity with the language and culture of the host country, or face challenges in obtaining work permits.

The report describes that exile does not always guarantee safety, as some countries resort to “transnational repression” methods to violate the human rights of exiled journalists beyond their territorial jurisdiction, aiming to intimidate and suppress them, creating a chilling effect that forces journalists to self-censor. These methods include violence, murder, surveillance, extradition, cyber violence, among others.

Finally, the report urges countries to establish clear legal pathways for journalists at risk to leave their countries to reside abroad where they can work and have the right to return safely until they can safely return home; ensure that exiled journalists are protected from violence, threats, and harassment, being expelled or extradited due to criminal charges related to their work; ensure prompt, full, and effective investigations and prosecutions of all transnational repression acts in their territory; amend national laws or enact new laws to prosecute those responsible for transnational repression.

“Chinese Human Rights” calls for abolishing Article 23

The U.S.-based human rights organization, Human Rights in China, also stated to the United Nations that since the passage of the National Security Law, “white terror” has become one of the biggest obstacles to the news industry in Hong Kong, with media’s fear of potential threats leading to widespread self-censorship. Exiled journalists are reluctant to return to Hong Kong, relying on second-hand information, hindering information exchange and fact-checking efforts. Acts of online interference and intrusion supported by the Chinese Communist Party frequently disrupt journalists’ lives and work.

The organization pointed out that the online space in Hong Kong continues to shrink, cutting off new overseas media and exiled journalists’ connections with Hong Kong, making it increasingly challenging to reach audiences in Hong Kong. Some Hong Kong residents are worried about subscribing to “sensitive media” due to potential backlash, causing significant drops in viewership, support, and engagement for relevant media outlets.

Mia Lam, the Director of the Human Rights in China project, criticized Article 23 of the Basic Law as a severe regulation that legalizes suppressing human rights and basic freedoms within and outside Hong Kong, targeting the news industry and freedom of speech. Apart from calling for the abolishment of Article 23, the organization also urged international society, news agencies, and journalist unions to safeguard the personal and financial security of overseas journalists through aid programs, grants, specialized visas, and other means.

Hong Kong’s Press Freedom Ranking Plummets

In May of this year, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) released the “2024 World Press Freedom Index,” where Hong Kong ranked 135th out of 180 countries and territories. Despite a slight improvement of five spots compared to the previous year, the score declined from 44.86 points to 43.06 points. Hong Kong’s ranking is lower than that of Zimbabwe (116th), Singapore (126th), Uganda (128th), and Cameroon (130th).

Regarding Hong Kong, Reporters Without Borders mentioned that there are still 10 journalists imprisoned; the report continued to reference the forced closures of Apple Daily and Stand News, with over five independent media outlets shutting down out of fear of reprisals.

In 2002, Reporters Without Borders first published the “World Press Freedom Index,” with Hong Kong initially ranking 18th globally. However, its ranking has been on a decline, plummeting from 80th place in 2022 to 148th place and further dropping to the 135th place this year.

—

This rewritten and translated news article covers the impact of the National Security Law in Hong Kong on press freedom, the challenges faced by exiled journalists globally, and calls for international action to protect journalists at risk.