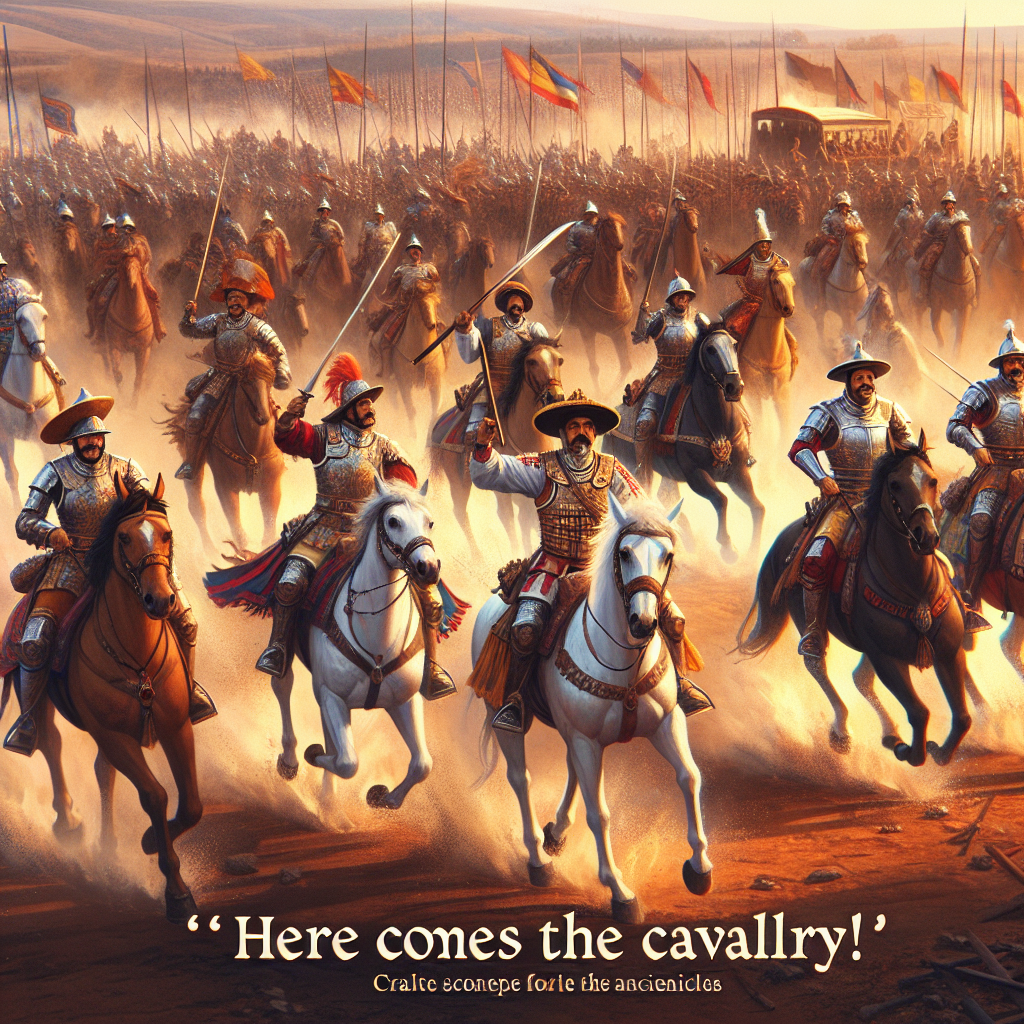

“Here come the cavalry!” This phrase has become a common saying to describe timely assistance appearing at critical moments. Its historical origins prove the significant role of horses and their riders in military history, including in American military history.

Horses appeared on ancient battlefields, sparking a military revolution. The power, speed, vision, and mobility brought by cavalry units allowed armies to gain significant advantages in many tactical scenarios. In comparison, infantry movements were slow and cumbersome, constantly having to deal with cavalry ambushes from various directions. The sight of knights clad in heavy armor thundering towards them in a cloud of dust was undoubtedly chilling for infantry soldiers.

One of the earliest evidence of horses being used in warfare is a Sumerian inlay dating back to around 2500 BC, depicting scenes of horses pulling chariots. By 1600 BC, chariots had become common, particularly in the Eastern regions. Several centuries later – around 900 BC, warriors often fought on horseback, and the development of saddles and stirrups significantly enhanced the combat effectiveness of cavalry units.

With the introduction of gunpowder in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, the way armed cavalry fought began to change. Heavy cavalry legions were replaced by more nimble and agile squadrons. However, horses still played an important role in armed conflicts, up until the 19th century and even continued to be used in a limited way in the 20th century.

The U.S. military has long valued its cavalry units, and the contributions of horses and riders have been particularly outstanding in the country’s past history.

During the early stages of the War of Independence, the continental army had almost no cavalry, but soon established cavalry regiments. The use of cavalry was interspersed throughout the war, although the terrain and tactical environment at the time were more suited for infantry, especially in the densely forested Northern colonies where the war initially erupted.

Several units were composed of light infantry and light cavalry. President George Washington’s exceptional horsemanship left a deep impression on Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson considered Washington the finest rider of his time, and various paintings of the general on his beautiful horse “Blueskin” adorned the walls of many art galleries.

The formal organization of the American cavalry began in the mid-19th century during the western expansion period. Their mission was to protect pioneers crossing the vast plains and deserts; the expansive lands of the American West were more suitable for cavalry operations, while infantry struggled to traverse arid regions quickly and were less effective.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, the Union army had a considerable number of cavalry units. Approximately three million horses participated in the war, undertaking various functions such as transportation, communication, reconnaissance, and combat.

In the early stages of World War I, many countries still heavily relied on cavalry, but the era of cavalry charges was nearing its end; new tactics and weapon technologies quickly changed the nature of warfare. Trenches, barbed wire, and machine guns rendered cavalry charges almost ineffective in most situations. Troops still used horses for transport, but horses were no longer the deadly weapons of war they once were. As the American Museum of Natural History puts it:

“Millions of horses perished in WWI, although by the end of the war, their role had shifted from shock troops to supporting roles. The clash of traditional warfare and new deadly technologies gave rise to poignant scenes like horses wearing gas masks, horses pulling cannons larger than themselves, and horses lying beside piles of mortar shell casings.”

What ultimately broke the trench deadlock was not the cavalry charges of yore, but the new mechanized death machine – the tank, slowly and steadily trudging across the scorched battlefields and desolate no man’s land of Europe.

Surprisingly, even as the effectiveness of “mechanized cavalry” (tanks) was proven in WWI, intense debates within the U.S. military continued on whether to continue using horses or transition to tanks. However, with technological advancements, the transition to tanks was inevitable.

The last cavalry charge of the U.S. military took place during WWII. On January 16, 1942, the 26th Cavalry Regiment near the village of Morong in the Philippines launched an attack and dispersed the Japanese forces. Additionally, horses were mainly used for transportation during WWII.

In more recent history, a small U.S. special forces unit known as the “Horse Soldiers” operated on horseback in the rugged terrain of Afghanistan, collaborating with Northern Alliance militias to combat the Taliban post 9/11. Furthermore, in modern military settings, horses primarily fulfill ceremonial functions.

Today, the remaining handful of cavalry units in the U.S. military primarily handle military funerals and parade duties. However, in recent months, the military has decided to disband most of these ceremonial units. Out of the Army’s existing 236 horses, mules, and donkeys, 141 will be transferred or given away.

The Army aims to save around $2 million annually by downsizing its horse units, which may also be a response to findings of neglect in animal care within the military discovered in a recent investigation. According to Military.com, after the deaths of some military horses in 2022, an assessment by the Army’s Public Health Command-Atlantic revealed instances of moldy feed, cramped and unsanitary living conditions for the horses, and inadequate veterinary care.

For a proud tradition in American military history, this is a rather somber conclusion. The heroic presence of war horses and riders has often turned the tide in American history, and the phrase “Here come the cavalry” has reignited hope in countless desperate moments for soldiers. The image of American cavalry and cowboys riding on loyal steeds is an important symbol of the American spirit; many of our nation’s achievements owe to this. Yet today, this scene increasingly becomes a memory of a bygone era.