In legal terms, Resolution 2758 only addresses UN representation of China and does not touch upon the sovereignty of Taiwan. The PRC has exercised its significant political and economic power to wield tremendous influence on various aspects of the UN system. This influence has translated into various measures that prevent Taiwan from having a presence, or participating, in the UN system and elsewhere.

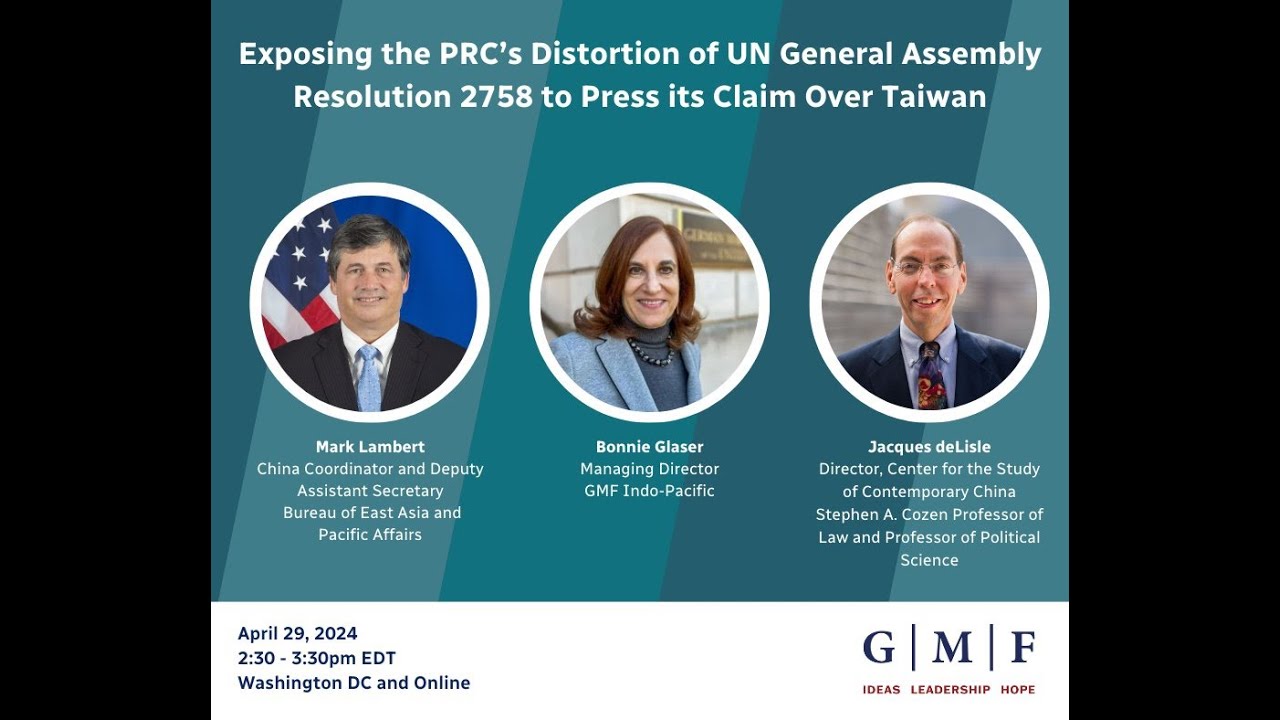

During a United Nations (UN) daily press briefing by the Office of the Spokesperson for the Secretary-General in May this year, the spokesperson responded to a question related to Taiwan by saying “on the issue of China, we are guided by the General Assembly resolution of 1971.” In a follow-up, the spokesperson further stated that “in terms of our standing on Taiwan as a province of China.” Speaking at a seminar held by the German Marshall Fund on 1 May 2024, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the State Department’s Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs publicly refuted that:

… firstly, that the resolution did not endorse, is not equivalent to, and does not reflect a consensus for China’s “one China principle”; secondly, that the resolution has no bearing on countries’ sovereign choices with respect to their relationships with Taiwan; thirdly, that the resolution did not constitute the UN taking an institutional position on the ultimate political status of Taiwan; and fourthly, that the resolution does not preclude Taiwan’s meaningful participation in the UN system and other multilateral forums.

This was not the first time the U.S.’ position on UN General Assembly Resolution 2758 (XXVI) differed from the interpretation expressed by UN officials. During a UN press briefing by the Office of the Spokesperson for the Secretary-General in March last year, a UN official was asked why the UN has shut the door on Taiwan, the most democratic country in Asia. Why are citizens of Taiwan not even allowed to enter the premises of the United Nations — be it the headquarters in midtown Manhattan, or hundreds other agencies worldwide? The spokesperson responded by mechanically reiterating the “one China policy” and maintained that only citizens of UN member states can enter the premises of the UN, which was soon contradicted by the practice of accepting Kosovo passports, as pointed out by the reporters at the press briefing. Why has Taiwan been excluded from the international community, in particular the UN system? Is this legitimate?

These questions touch upon the scope and application of Resolution 2758 and the implications of China’s persistent strategy to inflate and distort it. This paper explores the reasons for Taiwan’s long absence in international organizations, and its recent efforts to reengage. It then suggests the direction in which both the international community and Taiwan should move to better integrate Taiwan — a vibrant democracy that upholds universal values — into international society. Before doing so, it is necessary to take a closer look at what Resolution 2758 says, how it differs from the Beijing’s self-asserted “one China principle,” and explain how China’s assertion of the “one China principle” has no place in Resolution 2758.

The Exclusion of Taiwan in International Organizations and Lack of Diplomatic Relations

Taiwan’s exclusion is unsurprising, given China’s rise as a global power and omnipresent influence in the UN system and beyond. While attending General Assembly debates on September 25, 2022, China’s then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Wang Yi, stated:

The one-China principle has become a basic norm in international relations and a general consensus of the international community. Fifty-one years ago, right in this august hall, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 2758 with an overwhelming majority, which decided to restore the lawful seat of the People’s Republic of China in the United Nations and to expel the “representatives” of the Taiwan authorities from the place which they had unlawfully occupied. Once and for all, Resolution 2758 resolved, politically, legally and procedurally, the issue of the representation of the whole of China, including Taiwan, in the United Nations and international institutions. It completely blocked any attempt by anyone or any country to create “two Chinas” or “one China, one Taiwan.”

Interestingly, Taiwan’s former Foreign Minister, Joseph Wu, in response to Honduras’ switching to the PRC during an interview, declared that Taiwan does not rule out the option of dual recognition by third countries — that is, the simultaneous establishment and maintenance of diplomatic relations with both the PRC and Taiwan. Vast changes in international politics in the past few months have highlighted the bewildering case of the absence of Taiwan from the international system, both in terms of its systematic exclusion from most international organizations and its diplomatic relations with major countries.

In a post elsewhere, we argue that Taiwan acquired its statehood through self-determination by virtue of constitutional amendment and the democratization process commencing in the 1990s. Today, Taiwan possesses an international legal personality distinct from that of the PRC. One question we left unanswered is why Taiwan is generally excluded from the international community. A quick answer to this is that international political reality is driven by power politics, and in that realm China has significant and prevalent influence. Apart from this political dimension, there is a legal aspect of this exclusion resulting from constant misinterpretation — or more precisely, a calculated strategy of distortion by China — of Resolution 2758. The legal dimension and political dimension are intertwined and intermingled as China has long distorted and inflated Resolution 2758 and argued, groundlessly, that its “one China principle” derives from this resolution. Let us take a closer look at what Resolution 2758 says and why the PRC’s self-asserted “one China principle” finds no place therein.

What Does the UN General Assembly Resolution 2758 Say and Not Say?

On October 25, 1971, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 2758, which basically stated that the PRC would be the only legitimate government of China recognized by the UN. From that moment, the PRC replaced the Republic of China (ROC) as the sole legitimate government representing China in the UN, and took a seat as a permanent member of the UN Security Council. In the interest of clarity, we cite the resolution in full below:

THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY

Recalling the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

Considering the restoration of the lawful rights of the People’s Republic of China is essential both for the protection of the Charter of the United Nations and for the cause that the United Nations must serve under the Charter.

Recognizing that the representatives of the Government of the People’s Republic of China are the only lawful representatives of China to the United Nations and that the People’s Republic of China is one of the five permanent members of the Security Council.

Decides to restore all its rights to the People’s Republic of China and to recognize the representatives of its Government as the only legitimate representatives of China to the United Nations, and to expel forthwith the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek from the place which they unlawfully occupy at the United Nations and in all the organizations related to it.

The Scope and Effect of UN General Assembly Resolution 2758

Tellingly, this passage contains no mention of Taiwan or the ROC. Contrary to what the PRC persistently asserts, this resolution only addresses the representation of China in the UN — that is, the question of who is entitled to occupy China’s seat in the global body. It does not, in any sense, touch upon the territorial title of Taiwan. In fact, a recent report published by the German Marshall Fund details the historical context in which Resolution 2758 was passed. Competing proposals addressing the territorial title of Taiwan were advanced during the deliberation process, but did not obtain sufficient support. The majority of UN members agreed on the question of China’s representation, but nothing more than that.

China has distorted and inflated the scope of this resolution in an attempt to invent a legal foundation for its “one China principle.” In its recent white paper on “The Taiwan Question and China’s Reunification in the New Era,” the PRC elaborated on its “one China principle,” stating there is only one China in the world; Taiwan is an alienable part of China; and the PRC is the sole legitimate government representing China. The white paper further argues that “UN General Assembly Resolution 2758 is a political document encapsulating the one-China principle whose legal authority leaves no room for doubt and has been acknowledged worldwide, says the white paper. The one-China principle represents the universal consensus of the international community; it is consistent with the basic norms of international relations.” This syllogism constitutes the main thrust of the PRC’s “one China principle,” but the first two elements are far from clear or settled, in particular the question as to whether Taiwan is part of China. As mentioned above, Resolution 2758 is silent on this point and, as the historical evidence reveals, UN members were not able to agree on this point.

The PRC’s assertion that its “one China principle” has become a “basic norm in international relations,” and that there is a “general consensus in the international community,” is again perverting Resolution 2758 and a malign interpretation of various “one China policies” maintained by other countries. To begin with, principle has a different legal force than a policy. China arguably knows this, but it nevertheless attempts to conflate the two and confuse the international community. Secondly, “a basic norm in international relations” (which seems to be invented by China as it rarely, if ever, appeared in international relations in the past century), also differs from what is known in international law as “general principles of international law,” which has a clear definition and neat criteria. By using the wording “basic norms of international relations,” the PRC is trying to inject confusion, importing concepts that have legal binding force and general applicability into policies, which are by nature subject to change. Moreover, in a report published by Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Ian Chong highlights the differences between “one China policies” espoused by countries around the globe and concludes that while 51 countries agree fully on what the PRC terms “one China principle,” a large number of countries only acknowledge or take note of the PRC’s claim that Taiwan is part of China. By using these terms “acknowledge” “take note of” or “recognize,” these countries maintain an ambiguous posture on the question of whether or not they agree with, or are supportive of, the PRC’s claim that Taiwan is part of China. In particular, the United States, while maintaining relations with the PRC, adopted a “one China policy” that takes no position on the territorial title of Taiwan’s sovereignty, which in practical terms, means for the United States, Taiwan’s status is undetermined.

An Undue Practical Expansion of UN General Assembly Resolution 2758

In legal terms, Resolution 2758 only addresses UN representation of China and does not touch upon the sovereignty of Taiwan. The PRC has exercised its significant political and economic power to wield tremendous influence on various aspects of the UN system. This influence has translated into various measures that prevent Taiwan from having a presence, or participating, in the UN system and elsewhere.

In a letter of rejection to Nauru, a Pacific Island country which attempted to help table Taiwan’s ratification of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, then UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon explained why he could not accept the instrument by referring to Resolution 2758. Ban reportedly said, “In accordance with that resolution, the United Nations considers Taiwan for all purposes to be an integral part of the People’s Republic of China.” This statement invited criticism from some UN members, notably the United States. According to former U.S. diplomat John Tkacik, the U.S. in July 2007, presented a nine-point démarche in the form of a “non-paper” to the UN Under-Secretary-General for Political Affairs that restated the position of the United States that it takes no position on the question of Taiwan’s sovereignty and specifically rejected the Secretary General’s statement that the organization considers “Taiwan for all purposes to be an integral part of the PRC.” Moreover, a telegram by former U.S. ambassador to the UN Zalmay Khalilzad mentioned that in discussions with the UN Secretary General, “Ban said he realized he had gone too far in his recent public statements, and confirmed that the UN would no longer use the phrase “Taiwan is a part of China.” Australia, Canada, Japan, and New Zealand also consulted with the Secretary General and received the same commitment that the UN would no longer use that phrase.

Ban’s statement exposes a few critical issues. First, given that Resolution 2758 by no means addresses Taiwan’s sovereignty, the UN should not use this as a legal basis to bar Taiwan from participating in its organizations. Second, who has the authority to interpret the UN General Assembly resolutions? If the UN Secretariat, including its chief, moves beyond the boundary of administrative affairs by way of misinterpretation, who is in a position to sanction or correct it?

On a more general level, the treatises of public international law make clear the lack of legally binding effect of General Assembly resolutions. Accordingly to James Crawford and Ian Brownlie, while General Assembly resolutions “may have direct legal effect as an authoritative interpretation and application of the principles of the Charter,” they are normally considered as majority votes of the UN member states that “constitute evidence of the opinions of governments in the widest forum for the expression of [an] opinion” (emphasis in the original). Malcolm Shaw also stresses that “except for certain internal matters, such as the budget, the Assembly cannot bind its members. It is not a legislature in that sense, and its resolutions are purely recommendatory.” Of course, each individual resolution should be read in light of the historical and political context upon adoption, while also making reference to the opinions of member states on the matter. The bottom line is, General Assembly resolutions are not legally binding, but just the majority opinion of the UN member states on a specific matter at a given time.

A related issue is the policy currently maintained by the UN that Taiwanese citizens, namely those holding the passports of ROC (Taiwan), are not allowed to enter the premise of the UN. Is this policy an undue extension and misinterpretation of Resolution 2758? Does this exceed the administrative discretion of the Secretariat? Or does it constitute discrimination as people holding the passports of Kosovo, which is also not a UN member, are allowed to enter the UN? Such issues are beyond the scope of this paper, but call for a closer examination through the lens of international public authority or global administrative law.

Finally, both within the UN system and beyond, Taiwan is referred to as “Taiwan, Province of China.” This is common practice in UN agencies, and even organizations outside the UN family, notably under the International Standardization Organization. According to ISO, “[s]ince Taiwan is not a UN member it does not figure in the UN bulletin on country names. The printed edition of the publication Country and Region Codes for Statistical Use gives the name we use in ISO 3166-1. By adhering to the UN sources the ISO 3166/MA stays politically neutral.” Two more issues surface here. The first relates to the administrative discretion of the UN Secretariat. If Resolution 2758 does not address the sovereignty of Taiwan, is the Secretariat in a position to use the nomenclature of “Taiwan, province of China?” Secondly, is the ISO, an organization outside the UN system, by any means obliged to adhere to the UN practices? Again, UN General Assembly resolutions do not have legally binding power over members states, UN specialized agencies, not to mention organizations outside the UN system.

Road Ahead? Drop ‘Chinese Taipei’ and Debunk the Myth of UN General Assembly Resolution 2758

Due to the misinterpretation and undue expansion of Resolution 2758, Taiwan has been largely excluded from the international community, in particular the UN system. Taiwan, most frequently, participates in international relations under the abnormal name “Chinese Taipei,” which finds it origin from the participation of both Taiwan and China in the International Olympic Committee and its relevant activities. Such nomenclature is followed in Taiwan’s abbreviated title in the World Trade Organization and Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation as separate customs territories. The use of “Chinese Taipei” in various fora has the value of convenience, flexibility, and practicality. Nonetheless, it places Taiwan’s sovereign character at risk as it appears that Taiwan does not see itself as a sovereign state in accepting the name of “Chinese Taipei.” It is thus imperative for Taiwan to rethink its adherence to this nomenclature.

Looking forward, it is essential for Taiwan to make clear that it is a sovereign state distinct from China (or a Chinese state, if translated literally from Chinese), and is not represented by the PRC in the UN. Former President Tsai Ing-wen’s national day speech in 2021 reaffirmed her administration’s commitment that neither the Republic of China, nor the People’s Republic of China, should not be subordinate to the other. The current president Lai Ching-te, in his inauguration address also made clear that:

We have a nation insofar as we have sovereignty. Right in the first chapter of our Constitution, it says that “The sovereignty of the Republic of China shall reside in the whole body of citizens,” and that “Persons possessing the nationality of the Republic of China shall be citizens of the Republic of China.” These two articles tell us clearly: The Republic of China and the People’s Republic of China are not subordinate to each other.

However, the statement that neither side of Taiwan Strait is subordinate to the other does not necessarily lead to defining relations as “state-to-state” relations, although the Tsai and William Lai administrations have regularly reiterated that the ROC (Taiwan) is an independent country with sovereignty rested on its national population of 23 million people. Due attention should also be paid to the reference of Taiwan as “China” by the country’s limited alliance. A tricky case is the Guatemalan president’s recent reference of Taiwan as the “only and true China,” which may fall into the trap of competing for the representation of China (the Chinese state). For this reason, President Lai’s statements must be clearer, which may help to clear the doubts raised by Crawford in his seminal The Creation of States in International Law.

Finally, and most importantly, countries are free to adopt their own versions of the “one China policy” as opposed to the PRC’s self-asserted “one China principle” which finds no legal basis in Resolution 2758. While countries may maintain diplomatic relations with the PRC, it does not lead to the conclusion that they cannot have parallel diplomatic relations with Taiwan or that their official positions consider Taiwan part of Chinese territory or view Taiwan as not sovereign, as statehood and diplomatic relations do not always go side by side. It should be reminded that accommodating the PRC’s preferences and considering Taiwan as part of China risk emboldening China to attack Taiwan and de-legitimizes the intervention of third countries. In this line, it is of paramount importance that third countries clarify that their “one China” policies are conditional on the non-use of force, as enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations.

(Chien-Huei Wu is a research professor in Institute of European and American Studies, Academic Sinica; Ching-Fu Lin is Professor of Law, National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan.)