Later this month, a remarkably fast meteor shower will peak in the moonless night sky – providing ideal lighting conditions for observing shooting stars.

Named after the Orion constellation, the Orionids meteor shower appears to come from there but actually originates elsewhere. When it peaks on October 21st, coinciding with the night of the new moon, there will be no moonlight to interfere, offering stargazers an excellent dark environment.

The Orionids meteor shower may be visible as early as September 26th, albeit in smaller numbers. By November 22nd, they will have completely disappeared.

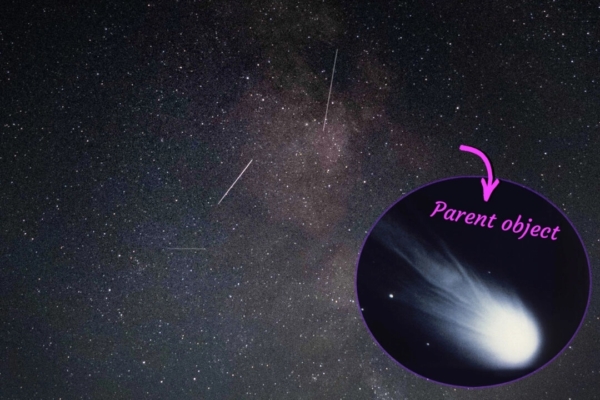

Meteor showers appear almost at the same time every year due to their position in space and Earth crossing through that area on its orbital path around the sun. As these meteors enter Earth’s atmosphere, they burn up and glow due to friction, creating the spectacle of a meteor shower.

The meteors’ origins lie in ancient space debris – composed of rock fragments and frozen gases – remnants left behind by comets orbiting the sun in the form of vast cosmic debris. When our planet, Earth, collides with this debris, meteors are born.

As they burn in the sky, meteors appear as flashing streaks of light. However, they are relatively faint and not as dazzling as fireworks. Meteors travel through space at speeds of several tens of miles per second, usually burning up entirely upon entering the atmosphere.

The Orionids meteor shower, though, moves faster than most meteors because they follow a retrograde orbit – meaning they move in the opposite direction of Earth’s orbit around the sun. They do not gently float in but impact head-on. The Orionids meteors can reach speeds of up to 41 miles per second.

Despite their speed, the Orionids meteors are not known for their brightness. They are dimmer compared to most meteors, but their long trails compensate for the lack of brightness. These trails, known as “persistent trains,” can last for several seconds after the meteor passes, caused by the glowing ionized gas left behind by the meteors.

The name “Orionids” might lead eager stargazers astray. Because they seem to radiate from the Orion constellation, observers might think that’s where to look. The point from which the meteors appear to originate is called the “radiant,” and the radiant for the Orionids meteor shower lies north of Orion’s belt, near the bright reddish star Betelgeuse. When observing meteors, it’s best to wait for the radiant to be high in the sky but avoid staring directly at it to spot the meteors.

Since meteors spread out in all directions from the radiant point, they can appear anywhere above the horizon. It’s best to lie back – on a reclining chair or blanket – to maximize the view of the sky and look around the radiant point for meteors. The best time to watch the Orionids meteor shower is from midnight to dawn.

Under a moonless sky, people can expect to see 10 to 20 Orionids meteors per hour. Fortunately, the new moon falls on October 21st, so moonlight will not interfere with this show.

If one were to trace the paths of these meteors back to the bright star Betelgeuse in Orion, they might mistakenly think they originate from there. However, Betelgeuse is over 500 light-years away from Earth, while the Orionids meteor shower is much closer – orbiting the sun and even directly colliding with Earth, making it impossible for them to come from Orion.

The apparent radiation from Orion is merely a perspective illusion. Just like train tracks seem to converge on the horizon, these meteors also seem to converge at the radiant point. They all move in parallel directions – like train tracks – and follow fixed orbits in space. Their intersection point with Earth remains constant, keeping their radiant point perpetually pointing to Orion, the hunter from Greek mythology, after whom the Orionids are named.

If not from Orion, then where do the Orionids meteors truly originate? The answer is – Comet Halley.

This comet, officially designated as 1P/Halley, is one of the few comets not named after its discoverer but after the first person to predict its return – Edmond Halley. It was first observed as early as 240 AD, over a thousand years before Halley’s time.

Though Comet Halley orbits the sun like a planet, it takes about 76 years to complete one orbital cycle. Whenever it nears the sun, solar radiation causes its icy surface to sublime into gas. The comet then releases material like a steam train, leaving behind a debris stream in its wake. When Earth intersects with Halley’s path each autumn, the Orionids meteor shower occurs.

After skimming past the sun, the comet will venture far away for over seventy years. Its second stream of debris also provides a “return performance” every May – as it is the source of the Eta Aquariids meteor shower as well.

Comet Halley last entered the solar system in 1986. Currently, it is at its furthest point in orbit – near Hydra – and will not return until 2061. However, its “offspring” – the Orionids meteors – continue to show up year after year. They serve as a reminder every October, that the distant parent comet still exists.

The original article titled “Super-Fast Orionid Meteors Will Fall to Earth This Month—but Where Do They Come From?” was published on the English version of The Epoch Times website.