Mercury is the closest planet to the Sun and also the smallest in the solar system. However, according to new research, beneath the surface of this dark gray planet, there may be a layer of diamonds as thick as 18 kilometers (11 miles).

We cannot determine the size of individual diamonds. Bernard Charlier, head of the Department of Geology at the University of Liège in Belgium, stated, “We don’t know how big they are, but diamonds are composed entirely of carbon, so in terms of composition, they should be similar to diamonds on Earth that we are familiar with. They appear to be pure diamonds.”

Charlier is one of the co-authors of this research report. According to him, these diamonds are located about 500 kilometers (310 miles) underground. Although they cannot be mined, these diamonds still have a chance to prove their existence.

Charlier explained, “Some of the surface lavas on Mercury are formed by melting from deep within the mantle. We have reason to believe that this process might, as it does on Earth, bring some diamonds to the surface.”

The research report was published in the June issue of Nature Communications.

These diamonds may have formed around 4.5 billion years ago when Mercury was just coalescing from dust and gas clouds, creating diamonds in high-pressure, high-temperature environments. It is believed that this young planet had a graphite crust, with a molten magma ocean beneath.

Researchers used a device called a hydraulic press, which simulates extreme environments, to conduct experiments mirroring those conditions. This device is commonly used to study material reactions under extreme pressure and is also used in the production of synthetic diamonds.

After melting the samples, scientists observed chemical and mineral changes under an electron microscope, discovering that graphite had transformed into diamond crystals. This enabled them to gain a deeper understanding of the secrets hidden beneath the surface of Mercury.

“We know that there is a significant amount of carbon present in graphite form on the surface of Mercury, but research on the planet’s interior is very limited,” said Yanhao Lin, a scientist at the Beijing Advanced Research Center for High-Pressure Science and Technology, who is also a co-author of the study.

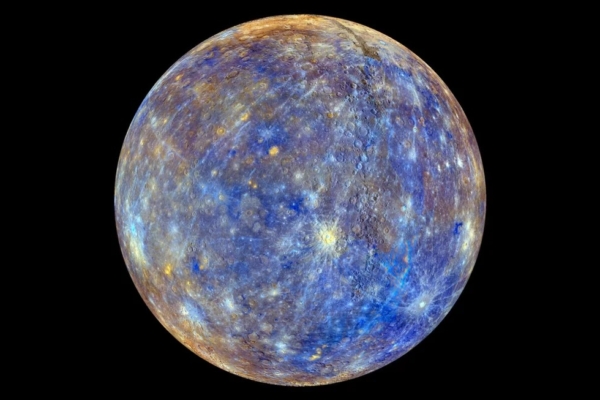

Mercury is the planet closest to the Sun and the smallest in size. However, it is also one of the least explored terrestrial planets in the solar system. According to findings from NASA’s MESSENGER mission, which took place from March 2011 to April 2015, Mercury is rich in carbon elements. The grayish appearance of its surface is due to the widespread presence of graphite, a carbon allotrope. Under specific pressure and temperature conditions, pure carbon can form diamonds. Researchers are interested in whether this process also occurred during the planet’s formation.

According to MESSENGER’s research, sulfur is also present on Mercury, leading to new discoveries about the planet’s internal state when Lin, Charlier, and their colleagues conducted simulation experiments.

“Compared to systems without sulfur, like Earth, Mercury’s magma can fully melt at lower temperatures, which is favorable for diamond stability because diamonds prefer high pressure but lower temperature environments,” Charlier explained. “This is our main finding from the experiments – that the temperature of Mercury’s magma ocean is lower than expected, and based on the reinterpreted geological and geophysical data from MESSENGER, we have learned that its depth is deeper than anticipated.”

Charlier estimated that the thickness of the diamond layer on Mercury is between 15 to 18 kilometers (9.3 to 11.1 miles), but this value may vary as the cooling process of Mercury’s core continues, affecting diamond formation.

According to CNN reports, scientists may soon learn more about the diamonds on Mercury. A mission named “BepiColombo” (consisting of two spacecraft launched in October 2018) is expected to enter Mercury’s orbit in December 2025 after a series of flybys. Led by the European Space Agency and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, this mission will study the planet from orbit, revealing more information about its internal structure and characteristics.