In recent years, as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has advanced its agenda of maintaining its power, it has changed the economic and social structure of China from the era of reform and opening up. More and more Chinese people feel that their dreams of success through hard work are becoming increasingly unattainable. The social class in China has become rigid, and the upward mobility for children from lower-income families has decreased.

张宇, who traveled to the United States in May this year, was a nurse at a top-tier hospital in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. She deeply resonates with this sentiment.

张宇 told Epoch Times that China is now in an era of “connections.” Without good connections, it’s impossible to get a good job.

“I have a friend who works in sports. He said no matter how his son performs, he can definitely get into a top university in China.”

She explained that the friend mentioned that as long as they obtain a national athlete certificate, scoring a few hundred points on the college entrance exam would secure admission to a good university. For instance, if the father is a coach for a provincial soccer or basketball team, he can arrange for his son to participate in a match, get the athlete certificates, and it’s done.

“While an average child studies hard every day, his child plays all day, scores a couple of hundred points, and still can enter a prestigious university.”

张宇 expressed that the government claims fairness and justice every day, emphasizing that education concerns everyone and forms the foundation of a nation. If even this cannot be fair and just, not to mention fairness and justice at a legal level.

Describing the dissemination of good jobs and positions in China as similar to “vertical transmission,” “blood transmission,” and “sexual transmission,” Zhang said that those truly talented individuals often do not have a place. They are left without jobs or income, trailing behind those with influential parents or those who have slept their way up the ladder.

张宇 lamented that present-day China is a society of privilege. Without privilege, one is like an ant easily crushed by others. With privilege, treatment and opportunities are inherently different.

“In our hospital, when the patients overflow, the corridors are full of patients lying everywhere. However, a room is always kept vacant, exclusively for officials or their relatives from the health commission or hospital management to stay in,” she said. Ordinary citizens might end up sleeping in the corridors for over ten or twenty days from admission to discharge, but those with privilege can occupy a room as soon as they arrive, and even get a private room to themselves.

“Not to mention the costs. Ordinary citizens have to pay all their medical expenses as stipulated, but those with connections often get away without paying. That’s just how it is.”

Liu Ao, currently living in the United States and enrolled at North China University of Technology in 2018, shared with Epoch Times that the students with the best academic performance in their dormitories are now the ones faring the worst.

One of his dormmates, who grew up in Beijing with well-connected parents, can earn multiple degrees without much effort, as their parents have arranged jobs for them in prestigious sectors like aerospace or telecommunications. Another friend’s parents have connections in a government agency, securing a job opportunity at China Central Television (CCTV).

Liu Ao noticed that many fellow students from families in the petroleum sector, who once aspired to work elsewhere, are now rushing back into the system.

“We all come from the same system, all educated in the schools for children of oil industry employees,” he said. Recalling their middle school days, they all dreamed about not following in their parents’ footsteps due to the system’s unfavorable conditions.

He explained that the petroleum sector has various constraints and rigid bureaucratic practices. For example, the child of a minor official speaks in an official manner in class, making others uncomfortable. This environment is not preferred by many, who hope to explore other paths rather than return to the petroleum sector. “We all have dreams – some yearn for arts, some wish to start businesses.”

However, these classmates eventually end up returning to the petroleum industry due to failure and changes in mindset. “Once in society, they choose to return to work in the oilfield as arranged by their parents.”

Nonetheless, Liu Ao observed that getting into the system after college has become increasingly challenging. “In the early 2000s, the petroleum sector still hired university graduates, but by the time I entered university, it had become very difficult to return to the industry, facing long waiting lists.”

Some of the schoolmates from specialized schools end up working as laborers at the production sites without formal employment, doing the most laborious tasks. Unable to find work outside, they continue this work until the day they can queue up for a position within the system.

“Many around me are still waiting in line. After all, most people’s parents are not high-ranking officials.”

While their salaries are not very high, deductions for social security and other expenses leave little remaining at the end of the month, but there is a sense of security. “There’s an uncle working at a government agency who, after 40 years of service, receives a retirement pension amounting to tens of thousands every month.”

“I suddenly found myself envying parents who did not attend university, perhaps not even high school, as they could be arranged jobs with better security right from the beginning.”

“Why do we struggle to get a higher education, only to end up in mediocre jobs,” he said. “I feel powerless – what’s the point of going to college? Even pursuing postgraduate studies doesn’t change the situation, and it’s frustrating.”

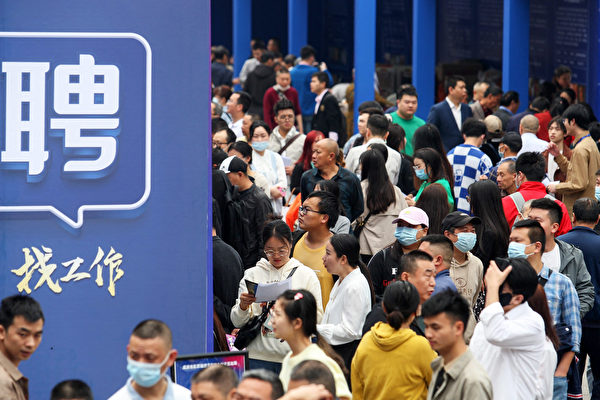

As the authorities crackdown on private enterprises, a sector that injected vitality into the Chinese economy and provided numerous white-collar jobs now shrinks. It’s increasingly difficult to find decent jobs, especially for commoners’ children.

A former project manager at an engineering company in Changsha, Hunan Province, Zhou Heng, told Epoch Times that finding a decent job for university graduates had become challenging as most desirable positions in China were monopolized by CCP officials or their relatives.

He explained that many job postings are merely for show, and even if outsiders apply, no matter how qualified they are, they might end up being sidelined in favor of someone connected. Zhou Heng expressed that the CCP’s system is like inbreeding; all the slightly better and more comfortable job positions are occupied by their own. In certain towns or remote areas, families mingle and provide assistance within their class, securing better jobs for their children.

Zhou Heng pointed out that it is extremely difficult for children of ordinary citizens to enter this circle. Unless they are genuinely talented and lucky, the vast majority of middle-class children struggle. Even if they manage to secure a position in a better organization, they end up doing the most laborious tasks without any prospects for promotion.