On July 15, 2025, the Chinese Communist Party’s “National Internet Identity Authentication” system officially went online, introducing the “NetID Net Number” system, also known as the “Internet ID Card,” to the public. In recent days, anonymous flyers opposing the system have appeared on the streets of Qingdao.

Despite the official announcement of a comprehensive schedule for mandatory implementation of the “Internet Identity Authentication” system, many people are concerned that this unified online identification system will be used for stricter internet control in the future.

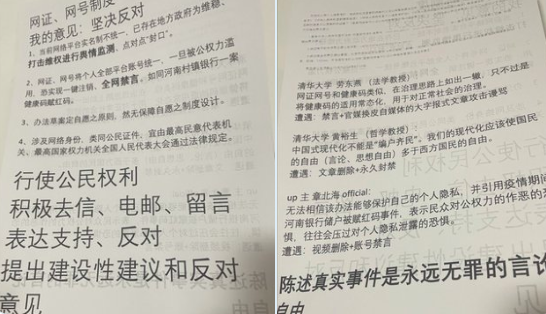

The flyers in Qingdao call on the public to voice their opinions to relevant authorities and be wary of the system potentially evolving into a tool to suppress rights defenders and block dissenting voices. One flyer, the size of an A4 paper, reads, “Once the ‘NetID Net Number’ is established, all online accounts will fall under unified monitoring, making account bans, group bans, and censorship more efficient and convenient.”

Photos of the flyers in Qingdao have circulated on social media platforms, with some netizens commenting, “This is an internet revolution that is not openly discussed. He who remains silent will be boiled. ‘1984’ was not a warning, but a prophecy.”

The Chinese Communist regime introduced the “National Internet Identity Authentication Public Service Management Measures,” jointly issued by six departments including the Ministry of Public Security and the Cyberspace Administration, effective as of July 15. The document stipulates that services on internet platforms require real-name registration or identity verification, with users able to complete the authentication through the “National Internet Identity Authentication” system. Officials claim that this system helps curb the over-collection and misuse of user information, acting as a “bulletproof vest” for personal information.

However, many interviewed individuals do not buy into the official explanation. Mr. Zhou from Nanchang, Jiangxi, expressed that while the system is introduced under the guise of “implementation,” there is an underlying implicit mandatory requirement. He stated that social media platforms, shopping platforms, and government apps will all eventually need to integrate with the NetID Net Number system. Those who don’t comply may face suspension or revocation of their accounts, effectively disappearing from the online space.

Mr. Qian from Huizhou, Guangdong, bluntly stated during the interview that this move by the authorities is aimed at silencing the common people. He sarcastically suggested, “Why not nationalize everyone’s QQ and WeChat IDs, and let the government operate all chat conversations, control friend circles, and determine what can be said.”

Mr. Zeng from Nanjing, Jiangsu, suggested responding to the system’s implementation with “non-cooperation.” He stated, “Stop using WeChat for overtime notifications, stop using DingTalk for clock-ins. Use silence and non-usage to resist these mandatory measures. If everyone stops using these platforms, it won’t be us who can’t endure, but these apps and the companies behind them.”

Many netizens pointed out that the vast majority of Chinese apps already require real-name binding with phone numbers, and the introduction of the NetID Net Number system simply further unifies platform management, facilitating official cross-platform account bans, tracking, and potentially suppressing rights defenders. One comment read, “This is not information protection but data centralization and labeling, locking everyone in a digital cage.”

A respondent from a southern city, Mr. Song, expressed that many of the Chinese Communist government’s regulatory policies often start as “voluntary,” then progress to “suggestions,” and eventually become “mandatory.” He likened this gradual approach to boiling a frog in water, where slight temperature increases go unnoticed until it’s too late.

Observers also noted the unusual low-profile approach to promoting the system’s launch. Since the Communist Party’s official media reported on the “NetID Net Number” policy two weeks prior to its implementation on July 15, there was minimal official promotion or guidance leading up to the launch date.

Some analysts believe this “low-key rollout” is a typical “depoliticization” approach used by the authorities to lower societal awareness, allowing the system to smoothly integrate before gradually increasing enforcement standards and diminishing public dissent.

Currently, critical details such as whether the NetID Net Number system will be universally mandatory, and the unified timetable for platform integration remain unclear. Meanwhile, some overseas observers are concerned that once online identities are tied to real names and all online activities are monitored, the Chinese Communist Party will find it easier to utilize technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data for monitoring speech, creating predictive law enforcement, and behavior scoring mechanisms.

A technology legal researcher who wished to remain anonymous told the media, “This is a typical national-level digital control system. From the efficiency perspective of data integration, it is undoubtedly one of the strictest means in the world, but it is still in the testing phase. At this moment, public reactions are particularly important; otherwise, it could easily become a new censorship tool.”