Scientists have made a groundbreaking discovery of dozens of young planets in a nearby nebula that could potentially challenge humanity’s existing understanding of the universe.

According to a report by BBC, these planets exist in a world that is fundamentally incomprehensible to humans. Unlike Earth in the solar system, these planets do not orbit within the confines of a star’s orbit but instead drift freely in pairs through space. With the assistance of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scientists have found these pairs of planets in the relatively nearby Orion Nebula in the Milky Way galaxy, defying traditional notions of planetary system formation.

Simon Portegies Zwart, an astrophysicist from Leiden University in the Netherlands, expressed disbelief at the existence of these planets, stating that they “should not exist” as they go against current understanding of star and planet formation.

These planets are referred to as Jupiter Mass Binary Objects, or Jumbos, and were discovered by former European Space Agency (ESA) astronomer Mark McCaughrean and Dutch astronomer Samuel Pearson. McCaughrean is currently working at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany.

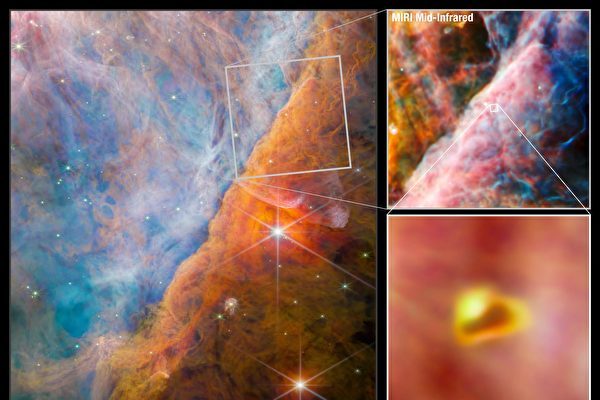

The two Dutch scientists have been using data from the JWST to study the Orion Nebula, located approximately 1,500 light-years from Earth. They were particularly interested in a young star-forming region spanning 10 light-years known as the Trapezium cluster and were astonished to find pairs of drifting Jumbos. This area has a history of only one million years.

According to McCaughrean, “This discovery was completely unexpected.”

The sizes of these celestial bodies vary, ranging from half the mass of Jupiter (the largest planet in the solar system) to 13 times the mass of Jupiter, indicating that they are likely all gas giant planets. Jupiter is approximately 11 times larger than Earth, making it one of the four gas giants orbiting the sun.

The distance between each pair of giant planets ranges from a minimum of 2.8 billion miles (4.5 billion kilometers) — the same as the distance between Neptune and the sun — to nearly 400 times this distance at maximum. In the Orion Nebula, each pair of Jumbos appears as twin points of light, seemingly orbiting each other.

Astronomer Jessie Christiansen from NASA’s Exoplanet Science Institute at the California Institute of Technology said that this discovery has put her exoplanet search team, which discovers planets outside the solar system, in a “crisis” mode because “one of our definitions of exoplanets is ‘planets orbiting other stars.'”

Freely floating planets have been discovered before and are believed to have been ejected from their original star systems due to the gravitational pull of passing stars. However, explaining how these giant celestial bodies ended up in pairs after being ejected from stars they once orbited is challenging.

In response, theoretical astrophysicist Rosalba Perna from Stony Brook University in New York and her colleagues proposed a theory where the two bodies were initially orbiting a star normally. When another star passed by, if they happened to be on the same side, they could have been ejected as pairs from their star system.

Portegies Zwart leans toward a different explanation, suggesting that the formation of giant planets follows the same process as stars, directly collapsing from gas clouds, known as in-situ formation.

“I think in-situ formation is the only method where I don’t encounter theoretical problems,” he said. “It’s the most promising explanation.”

To unravel the mystery, scientists need to conduct further observations of these objects. McCaughrean and Pearson are studying this case — this year, they conducted a more extensive study with JWST, using the telescope to analyze the light of the celestial bodies. Before they release their latest findings, they will search for traces of certain elements in the atmospheres of the giant planets that may hint at their origins.

If they formed around stars, they should contain heavier elements that may exist in the dust disks surrounding stars during planet formation.

Another option is to study the Jumbos with radio telescopes and track their movements in the sky. If these two pairs of stars are moving away from a common star at the same speed, it could support the idea that they were ejected planets. If not, it may imply that the in-situ formation theory is correct.

Astronomer Luis Rodriguez from the National Autonomous University of Mexico has successfully observed radio signals from one of the largest pairs of giant planets. Such radio signals are not surprising. Rodriguez said, “This may be related to the interaction of their magnetic fields.” Perhaps these celestial bodies possess particularly strong magnetic fields due to their young age, resulting in more powerful dynamic effects from the rotating cores.

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, set to be launched by NASA in 2027, can also study giant planets. The telescope will survey the universe to search for exoplanets but can also be used to study objects within the Orion Nebula, potentially discovering even more giant celestial bodies than detected by the JWST.