In a move described as the largest industrial policy initiative in the United States since World War II, the Biden administration has formulated its most significant new industrial policy in decades to help the U.S. maintain an absolute technological edge over communist China. The White House’s chief technology advisor, Arati Prabhakar, a rare semiconductor expert with a defense background, is at the forefront of this effort. Let’s take a closer look at Prabhakar and other technology advisors’ interpretations and perspectives on the Biden administration’s tough stance towards China.

Arati Prabhakar, the current director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and Biden’s chief technology advisor, remarked to The Washington Post, “For decades, our models have been too simplistic. That overly simplified model is letting the market and globalization solve all problems.”

For thirty years, the U.S. has immersed itself in the waters of globalization, believing that a rising tide lifts all boats and that the U.S. would rise highest. However, China’s technological rise has caught the U.S. off guard, leading to a broad reversal in U.S. policy towards China—from appeasement to a more confrontational stance.

Prabhakar, the first White House senior technology official with a defense background since the Cold War, embodies the consensus in Washington behind the tough approach towards China. She previously served as the head of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), overseeing future technology research at the Pentagon. She led the development of an autonomous ship for a secret military research institution.

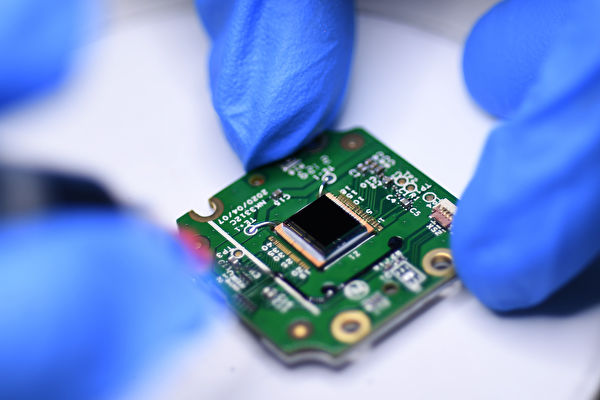

Her earlier expertise in semiconductor research is rare among senior policymakers in the White House, where most predecessors have had backgrounds in biology, meteorology, and other fields. Leveraging her expertise, Prabhakar has helped the Biden administration craft its most extensive new industrial policy in decades to maintain America’s technological edge over communist China, with semiconductors as a core focus.

Gary Hufbauer, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Department of the Treasury and senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, commented, “This is the largest industrial policy move in the U.S. since World War II.”

Born in India and immigrating to the U.S. with her parents at a young age, Prabhakar earned a Ph.D. in Applied Physics from the California Institute of Technology. In the late 1980s, she joined DARPA during the end of the Cold War.

Reflecting on her time at DARPA, Prabhakar noted, “When I was at DARPA, the Soviet Union disintegrated, and I saw a profound shift in our views on national security.”

Following the Soviet Union’s dissolution in 1991, a colleague of hers briefed General Colin Powell, then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, on submarine situations, to which Powell remarked they were no longer concerned with submarines. Washington downsized U.S. military forces, embraced globalization, and believed the uncontestable and unshakable global leadership position of the U.S.

Rob Atkinson, founder of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, recalled, “We were riding high. We were the center of the network and IT economy. China was nothing. … We thought this would go on forever.”

However, the unexpected emergence of communist China as a significant technological competitor to the U.S. has sent a chill reminiscent of the Cold War. President Trump began adjusting U.S. policy towards China, shifting from decades of appeasement to a hardline confrontational stance and launching a trade war with China.

During his 2020 presidential campaign against Trump, Biden harshly criticized Trump’s tough stance on China. Yet, since assuming office in 2021, Biden surprised many by not only retaining but strengthening Trump’s tariffs and export controls on China, albeit with more cautious rhetoric to avoid fostering anti-China (or anti-Chinese) sentiments.

Kevin Wolf, former Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Export Administration responsible for export management, stated that the Biden administration has implemented the strictest technology export controls on communist China in recent years. The policy position is that China has the capability to produce advanced computing systems on its own, posing a national security threat to the U.S.

Jake Sullivan, Biden’s national security advisor, declared in September 2022 that the U.S. must no longer maintain a “relative” technological lead over competitors but must “maintain the largest lead possible.” Shortly after, Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo led the Department of Commerce in initiating a series of technology export controls on China.

Prabhakar was appointed as Biden’s technology advisor in October 2022 at the age of 65. Her office is located in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building adjacent to the White House.

Facing tough challenges, Prabhakar’s team in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy is tasked with accelerating innovation in U.S. military technology, including semiconductors, telecommunications, and quantum computing, while simultaneously restricting research connections between the U.S. and China.

Many of these projects’ completion timelines extend far beyond the four-year presidential term, indicating an ongoing tech competition with China that could last for decades, akin to the Cold War era.

Prabhakar’s team is formulating long-term research and development strategies, guiding research projects on quantum computing and cancer treatment, and striving to persuade multiple institutions to collaborate to allocate more radio frequency spectrum for emerging technologies to realize the leap to 6G technology.

The team is also working to secure commitments from allies to support American 6G wireless network technology over China’s 5G. Deployment of 6G technology is projected to begin around 2030.

Discussing the establishment of a 6G alliance around the U.S. position, Prabhakar stated, “Now is the right time to start uniting everyone.”

In August 2022, President Biden signed the $52 billion Chips and Science Act into law, driving industrial policy in critical technology areas such as chips and telecommunications equipment. These policies have garnered bipartisan support in the U.S.

Telecom expert Ken Zita, who advises the Biden administration on industrial policy, noted that federal industrial planning in the U.S. had been severely outdated for years, transitioning from having “no industrial policy” to having one.

He remarked, “They had to start from scratch, constantly asking, ‘What can we do? Where can we take action?'”

Prabhakar’s team is drafting security guidance for universities nationwide on how to restrict and monitor research relationships with China and other countries perceived as rivals. This task was inherited from the Trump administration.

Prabhakar mentioned that her team is now “very close” to finalizing the rules. After receiving feedback on the rules’ draft from academia last year, concerns were raised about the overly intricate requirements for universities, leading to delays in the final version.

Critics argue that the Biden administration’s export controls on China are more rooted in trade protectionism than national security needs.

Prabhakar disagrees with this view, emphasizing that these controlled policies are part of a thoughtful long-term plan aimed at ensuring America’s competitive advantage.

Former Commerce Department Assistant Secretary Wolf remarked, “When I travel overseas—speaking about Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Switzerland, Germany, Netherlands, UK, these allied countries—almost from country to individual, they don’t really understand what the national security objectives are, and the U.S. government is trying to achieve those objectives through all of these new controls.”