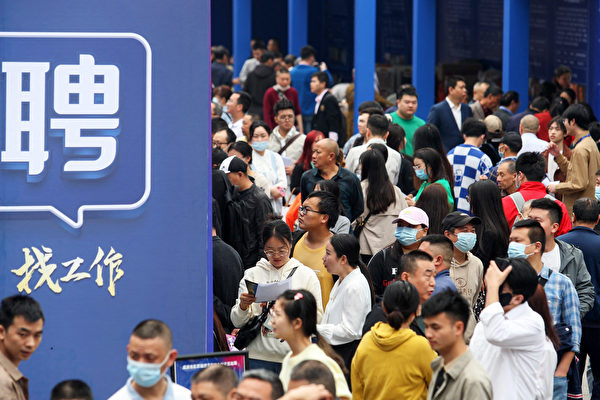

In July, the graduation season in China has once again raised concerns about the employment situation of university students. According to official statistics, in 2025, the number of Chinese university graduates is expected to reach 12.22 million, an increase of 430,000 from 2024, reaching a historic high. The youth unemployment rate in China remains high, with serious devaluation of degrees. Nowadays, a master’s degree is equivalent to a bachelor’s degree in the past, and many university students pursue postgraduate studies just to secure a job.

In 2023, the youth unemployment rate for the 16 to 24 age group, including students, reached a record high of 21.3%, significantly higher than similar indicators in major Western countries. In July 2023, Professor Zhang Dandan of Peking University calculated that the actual youth unemployment rate in China was as high as 46.5%.

After reaching record highs, the Chinese Communist Party officials chose to “cover up” by announcing the suspension of publishing youth unemployment rate data in mid-August 2023. It wasn’t until January 2024 that the data was reissued, but the new unemployment statistics did not include students. Analysts believe that this data contains many “human adjustments” and is difficult to trust.

The Washington Post interviewed several Chinese elite graduates, including Crystal, a graduate of Peking University, whose goal was to enter top technology or financial companies. She participated in case competitions at an American management consulting company Bain & Company during her studies, had internships at four tech companies including TikTok and Xiaohongshu, and graduated in the top 10% of her class in 2023.

However, after graduation, she had only one choice – to pursue another two years of graduate studies to obtain a master’s degree in economics and management before entering the workforce.

Crystal said, “When we graduated, the economic prospects were quite bleak, and now after graduating from undergraduate (university), we can no longer find a job. Students from Peking University who graduated in 2014 could find decent jobs and live comfortably, but we can’t.”

Crystal’s example reflects the plight of Chinese graduates in recent years. Even graduates from top universities find it difficult to secure jobs, let alone the average university students.

The Washington Post pointed out that 54% of Tsinghua University graduates in 2013 pursued postgraduate courses, a figure that rose to 66% in 2022. In 2019, 48% of Peking University graduates pursued master’s or doctoral degrees, which increased to 66% in 2024.

Nancy Qian, an economics professor at Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University in the United States, stated that today, students pursue master’s degrees not to seek higher salaries, but to find employment. Even elite graduates have to “exert all their efforts” to find a job with a very average salary, which “is simply not enough for them to live independently.”

One of China’s largest online recruitment platforms, Zhaopin, analyzed in its 2023 report, stating that “having a graduate degree… only serves as a ticket to entry.” “Whether you can find a good job still depends on your abilities… having a degree is just the minimum requirement for job seekers, not an advantage.”

Qi Mingyao, the founder and CEO of a telecommunications company in Beijing, pointed out, “When I entered university in 1992, 100% of undergraduate students could find jobs after graduation, and they could find good jobs.” “Master’s students today are like undergraduates back then, and today’s undergraduates are like vocational school students back then.”

He mentioned that his company, which had about 60 employees before the epidemic, has now reduced to only about 20 employees. Due to poor operational conditions in recent years, the company has not recruited new staff.

Qi Mingyao stated that if the company were to resume hiring, he would seek graduates with master’s degrees because “we need people to develop software, and graduate students have more professional skills than undergraduate students.”

Nancy Qian noted that since the late 1970s reform and opening up, China has experienced waves of unemployment, and what is surprising about the current employment crisis is that it is hitting the populations that are often considered the safest, namely the elite from prestigious schools.

The young graduates from these prestigious schools are now feeling very frustrated, wondering, “What is the point of all this? Why should we work so hard? Maybe we should just give up.”

Qian pointed out that the next generation of prospective parents “believe that they do not have the financial means to get married and have children.” “When a large number of young people are unemployed, all normal mechanisms for people to meet, socialize, get married, have children, and build families will collapse.”

(This article refers to The Washington Post’s coverage)