The Zhangjiajie Dayong Ancient City, which cost nearly 2.5 billion yuan to build, has incurred losses exceeding 1 billion yuan in the four years since its trial operation began in 2021. Once considered a flagship cultural and tourism project for the city, the ancient city has now become a “hollow scenic area” plagued by financial woes, reflecting the broader issue of unfinished cultural and tourism projects across China.

Recently, a netizen commented on People’s Daily website suggesting strategies for Zhangjiajie’s cultural tourism sector, such as partnering with other attractions for package deals and providing shuttle services to transport tourists to different locations, aiming to improve visitor services and attract more tourists. The response from the Zhangjiajie municipal government to this suggestion has attracted attention.

Zhangjiajie, historically known as Dayong, named the cultural tourism project “Dayong Ancient City,” led by the state-owned Zhangjiajie Tourism Group. Originally intended to set a national example of cultural tourism, the project was expected to generate nearly 500 million yuan in annual revenue with a net profit of close to 200 million yuan.

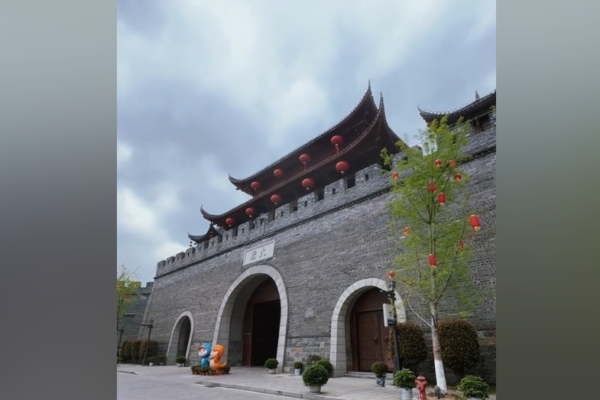

According to the China Urban Planning Society, the Dayong Ancient City project covers approximately 325 acres with a total construction area of around 185,000 square meters. The architectural style combines elements of Ming and Qing dynasties with Tujia ethnic features, featuring facilities such as theaters, temples, and archways. The local government invested about 25 billion yuan in the project, which was approved in March 2016, commenced construction in June 2016, started trial operations in June 2021, and was fully completed in August 2022.

However, the Zhang Tourism Group has never been profitable in its operation, with accumulated losses reaching 1.08 billion yuan over the four years. By the end of 2024, the total assets of the Dayong Ancient City Company amounted to 1.395 billion yuan, total liabilities were 1.697 billion yuan, resulting in a net assets deficit of 302 million yuan. In September 2024, the Dayong Ancient City entered a judicial reorganization process with plans to revitalize assets through debt restructuring. Progress on the restructuring plan was reportedly made by July 2025.

Currently, the initially designed 198 street-side shops in Dayong Ancient City remain closed. With a daily visitor count of fewer than 20 people, the only profitable element in the area is the parking lot.

The Dayong Ancient City is just one of many unfinished projects in China’s cultural tourism sector. The industry began in the late 1980s and 1990s, focusing on historical and cultural heritage tourism managed by the government, with ticket sales as a core revenue source.

After 2000, various regions rushed to develop cultural tourism areas, towns, and themed streets, incorporating them into GDP assessments and investment projects. Due to excessive construction and severe homogenization, fake ancient towns and replica streets became prevalent, leading to criticism of “one town, one style” and “cultural distortion.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, severely impacting the tourism industry with a sharp decrease in visitors, many cultural tourism projects could not operate or were put on hold. According to mainland media “New Travel World,” the top project on the “unfinished list” with a total investment exceeding 95 billion yuan was the Shanshui Wen Garden.

On July 29, 2025, Economic Daily reported that there were over 2,800 artificial scenic areas constructed nationwide, but less than 300 survived to date.

Drawing insights from various perspectives, journalists analyzed three major issues plaguing China’s cultural tourism industry:

From south to north, there is a proliferation of “replica ancient scenic areas” and “cultural towns.” However, the development model of these areas involves government land allocation, real estate development, capital investment speculation, and rent collection, with tourism as a superficial facade but essentially controlled by government-led capital operations.

According to a report on August 3 by “Travel World,” based on industry insider Mr. Xu’s disclosure, the operation of Xu’s cultural tourism project is based on a comprehensive EPCO (Engineering, Procurement, Construction, Operation) bundling model spanning construction, financing, investment attraction, and operation.

Mr. Xu stated that the operating teams engaged in EPCO projects are not knowledgeable about cultural tourism but merely have numerous brands and can write investment brochures, with the most critical element being obtaining government funds for rural revitalization. Through interviews with Mr. Xu, “Travel World” reported that local governments understand the challenges of cultural tourism but have no choice due to the pressure for achievements. Rural revitalization needs to show results, and large ancient towns need to be developed, meaning the fiscal budget must be fully utilized. The so-called EPCO cultural tourism projects are not designed for tourists but as a part of the governance achievements.

According to a report on Sohu, the parent company of Dayong Ancient City is Zhangjiajie Tourism Group Co., Ltd., a locally supervised listed company with the Zhangjiajie City Government’s State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission as the actual controlling entity.

China issues expert Wang He told Epoch Times, “Zhangjiajie was originally a tourist attraction with high foot traffic. The Dayong Ancient City should have had a certain market foundation, but it was a decision made by the government rather than market operations.”

“This is a product of the distorted achievement view under the Communist regime. Local government competition for GDP growth, achievements, and city appearance as the facade have led to a plethora of cultural tourism projects. These projects are political creations rather than market-economic products, with poor economic viability, primarily serving political purposes rather than market demands, resulting in widespread failures.”

The area where the Dayong Ancient City is located previously had authentic historical streets. However, before the project started, these historic districts were heavily demolished and replaced with “replica ancient streets.”

According to reports by the China Urban Planning Society and Xinhua News Agency during the project launch, the Dayong Ancient City was situated at the original site of the Ming and Qing dynasties at the south gate of Zhangjiajie City, “preserving and repairing historical and cultural landscapes such as Sanyuan Palace, Chaotian Gate, ancient city walls, ancient trees, and reconstructing intangible cultural heritage performance venues like Yangxi and ancient music halls, aiming to recreate the ten-scenery landscape of the Dayong City during the Ming and Qing dynasties.”

However, several media reports highlighted the extensive “demolition of the old in favor of the new” during the implementation of the Dayong Ancient City project: old urban areas were razed, many historical buildings were demolished, and besides Sanyuan Palace, other traditional elements such as Nanzhou Wharf, blue-stone streets, and stilted buildings were replaced with replica architecture.

Reports from Tencent News, 36Kr, and Global Travel News described this practice as a typical case of “destroying the authentic and building the fake”: genuine historical districts were not preserved, resulting in highly commercialized and culturally lacking replica attractions. Visitors to such ancient cities often feel like they are “consuming in a movie set” with everything appearing artificial.

Wang He believes, “This is a distortion. Genuine cultural relics can evoke a sense of respect in people. However, the CCP has vigorously destroyed these true cultural relics, establishing a series of fake antiques and fake cultural artifacts. This not only deceives consumers but also deceives the market. Essentially, it’s a reign without regard for order, promoting cultural nihilism.”

Moreover, the Dayong Ancient City lacks planning for living spaces and public areas, leaving it predominantly as a commercial space. Wang He remarked that at this stage, it ultimately “is not an ancient city but a modern commercial district” that should have preserved cultural memories but instead became a cheap “fast-moving consumer goods.” The original residents were “relocated,” their traces of life were erased, and replaced by uniformly dressed “actors” pretending to be ancient people performing.

Changjiang Research Report stated, “Culture has become a performance, and life has turned into a spectacle, intensifying this sense of disconnection.”

Truly attractive ancient towns, like Fenghuang, Pingyao, and Lijiang from some years ago, have a vibrant living atmosphere, embodying “living culture.” Streets filled with elderly residents basking in the sun, the smell of cooking and laundry in the air, and neighbors greeting each other on familiar streets are scenes of reality. These ancient towns are not solely dominated by scenic area management, ticket sales, and commercial stores.

Wang He said, “It’s all about ‘following the money,’ presenting the project superficially as high-end but, in reality, it is a profit scheme and an achievement project. It’s a vast construction spree, a swarm of officials rushing in, with corruption rampant throughout the process.”

Journalists believe that China has an abundance of cultural resources but lacks reverence and planning. Thus, maybe “building fewer replica ancient cities and preserving more old streets” is the truly sustainable path, offering tourists the authentic cultural travel experiences they truly seek.