In China, the supply of rare earth elements may be interrupted at any time due to policy changes, prompting Western companies to adopt the “China+1” or “China+N” strategy, even if it means paying higher premiums. Furthermore, these companies are increasingly turning to Brazil or other regions for mining, often using more environmentally friendly practices and gaining acceptance from local communities.

According to a report by The Wall Street Journal, in a mining pilot plant in Brazil, a technician is training workers to separate metal-rich clay rocks from piles of red soil. These metals are crucial for producing electric cars, smartphones, and missiles, with the destination being the United States rather than China.

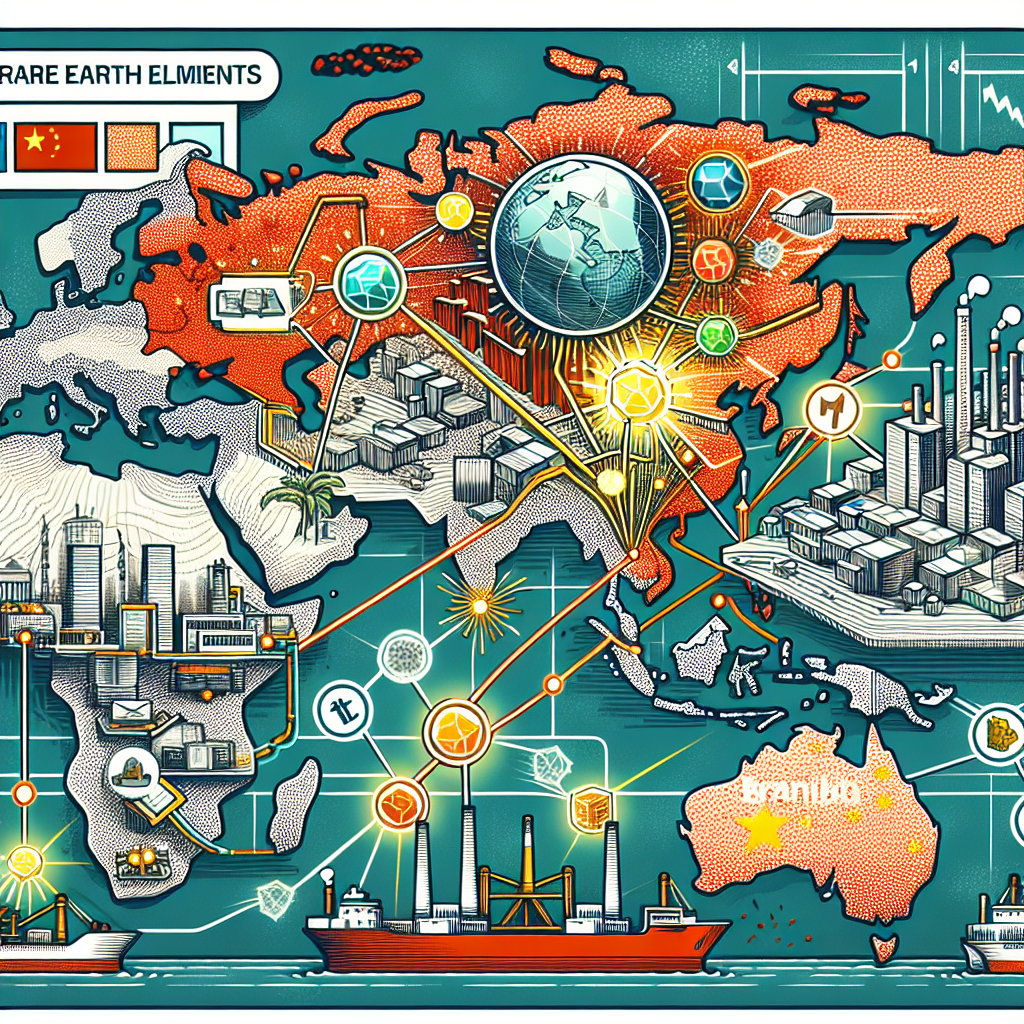

China dominates global rare earth mining and production, accounting for about 70% of mining and 90% of processing. Many countries’ rare earth ores are also shipped to China for refinement, which is a major concern for countries like the United States striving to secure a complete rare earth supply chain.

In April of this year, following the imposition of new tariffs on Chinese goods by the United States, Beijing tightened export restrictions on rare earth materials. In May, with the U.S.-China agreement reached and both sides temporarily lowering tariffs, Beijing resumed rare earth exports to certain companies.

Despite this, in the escalating geopolitical environment between the U.S. and China, Western manufacturers, including Tesla, are intensifying efforts to find alternative sources of rare earths outside of China.

Ramón Barúa, CEO of Canadian company Aclara Resources, stated in an interview with The Wall Street Journal, “We are witnessing a situation where demand is surging like a tsunami.”

Barúa mentioned that the company is mining a rare earth deposit in Brazil and plans to supply raw materials to a processing plant it intends to build in the U.S. The processing plant will separate the rare earth ore into individual elements.

As early as 2024, the German company VAC signed a rare earth supply agreement with Aclara and received $94 million in funding from the Pentagon to build a factory in South Carolina, producing rare earth magnets for customers like General Motors.

According to data from the U.S. Geological Survey, Brazil’s rare earth reserves are estimated at around 21 million tons, ranking second in the world after China.

Brazil also possesses abundant heavy rare earth resources, such as dysprosium and terbium, two silver-white metallic elements crucial for maintaining magnetism in high temperatures, essential for electric vehicles.

In 2020, former U.S. President Trump declared a national emergency to address America’s foreign dependence on key minerals like rare earths. Upon returning to the White House in 2024, he once again prioritized the issue.

Over the past five years, the U.S. has invested hundreds of millions of dollars to rebuild rare earth processing plants and magnet factories that have closed over several decades dominated by China.

Europe is also striving to reduce its reliance on China’s rare earth industry. The goal is to process at least 40% of key raw materials within the EU and ensure that supply from any single external country for designated materials, including rare earths, does not exceed 65% of EU annual consumption.

Previously, due to the higher extraction and processing costs of rare earths in Brazil compared to China (approximately three times as much), Western buyers favored purchasing from China. However, with the potential for supply disruptions in China, Western buyers are now adopting the “China+1” or “China+N” strategy, even if it means paying higher premiums.

On May 16, Australian rare earth company Lynas Rare Earths announced the successful launch of heavy rare earth separation production of dysprosium oxide outside of China, making it the first supplier to achieve commercial heavy rare earth processing.

Additionally, Western companies typically employ more environmentally friendly practices in mining in Brazil or other regions, making it easier to gain acceptance from local communities.

In contrast, Chinese-owned mining operations overseas have faced numerous issues. In February 2025, a large tailings dam collapse occurred at a major Chinese-owned mine in Zambia, releasing about 50 million liters of waste containing concentrated acid, dissolved solids, and heavy metals into a major river, resulting in the deaths of nearby birds and fish almost overnight.

Days later, another small-scale acidic waste leakage occurred at the same site, resulting in the death of a miner who fell into the acidic substance. Authorities also found that the mine continued operations after being instructed to cease, leading to the arrest of two Chinese mine managers.

China’s rare earth extraction method typically involves drilling into clay, then leaching rare earths with an ammonium sulfate solution (a common fertilizer). This process is cost-effective but may contaminate surrounding soil and water sources.

In contrast, Aclara’s mining involves digging clay from approximately 30 meters (about 100 feet) underground and transporting it to a processing plant. Since the clay is near the surface, there is no need for deep excavation, and the residual clay is washed and returned underground without constructing tailings dams.

Rare earth expert Jon Hykawy recently visited Aclara’s pilot plant and mine in Brazil. He told The Wall Street Journal, “The biggest difference between China and Aclara in Brazil is whether they care about environmental protection.”