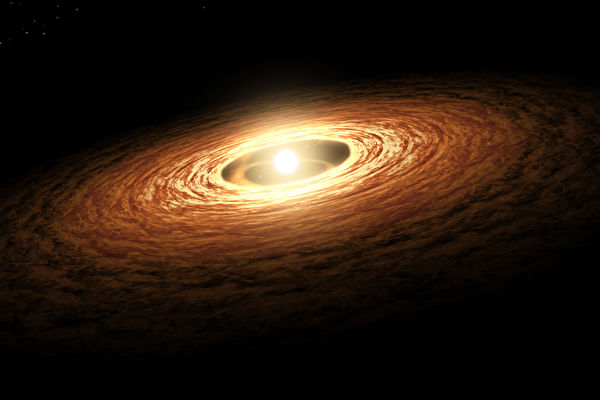

Astronomers have discovered a significant amount of carbon-containing molecules within a disk-shaped structure of gas and dust surrounding a young star. This marks the largest amount of carbon molecules found in such a disk-shaped structure to date and the first detection of ethane outside of the solar system. This discovery suggests the possibility of planet formation around the star.

According to a press release issued by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) on June 6, rocky planets are more likely to form around low-mass stars than gas giants, making rocky planets the most common type of planet around stars in the Milky Way galaxy.

Very little is known about the chemical composition of these worlds, which could either be similar to Earth or vastly different. By studying protoplanetary disks around stars where planets can form, astronomers hope to gain a better understanding of the process of planet formation and the composition of planets once they are formed.

Protoplanetary disks around very low-mass stars are challenging to study as they are smaller and more indistinct compared to disks around higher mass stars. With the assistance of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers are able to study these protoplanetary disks in greater detail.

In a new study, an international team of astronomers observed the protoplanetary disk of the low-mass young star ISO-ChaI 147 using the James Webb Space Telescope.

ISO-ChaI 147 is located approximately 600 light-years from Earth. It is only 1 to 2 million years old and slightly more massive than the Sun by about 10%. The observations revealed 13 different carbon-containing molecules within the protoplanetary disk around this star, the largest amount of carbon molecules found in a protoplanetary disk to date.

These carbon molecules include ethane (C2H6) detected for the first time outside of the solar system, as well as ethylene (C2H4), propyne (C3H4), and methyl radical (CH3).

Lead author of the study, researcher Aditya Arabhavi from the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, noted that these carbon-hydrogen compounds are not only diverse but also abundant. He expressed surprise at seeing these molecules dancing in the cradle of planets, highlighting the unique environment for planet formation.

Due to the abundant carbon molecules in this protoplanetary disk, the solid materials that can form planets may contain very little carbon. As a result, the planets that form in this system may be low in carbon content, similar to Earth.

Another researcher from the University of Groningen, Inga Kamp, pointed out that the composition seen in disks around low-mass stars is vastly different from what is observed around Sun-like stars, where oxygen-containing molecules such as water and carbon dioxide dominate.

Agnés Perin, a researcher from the French National Center for Scientific Research involved in the study, added, “It is incredible that we can detect and quantify molecules we know well on Earth, such as benzene, in an object over 600 light-years away.”

The research team plans to expand their study to a larger sample of protoplanetary disks around low-mass stars to further understand how common or unique carbon-rich planet formation regions like this are.

Thomas Henning, a researcher from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany, emphasized that expanding their research will lead to a better understanding of how these molecules are formed. He mentioned that there are still several unidentified features in the observational data from the James Webb Space Telescope, indicating the need for more spectra to fully decipher the results.