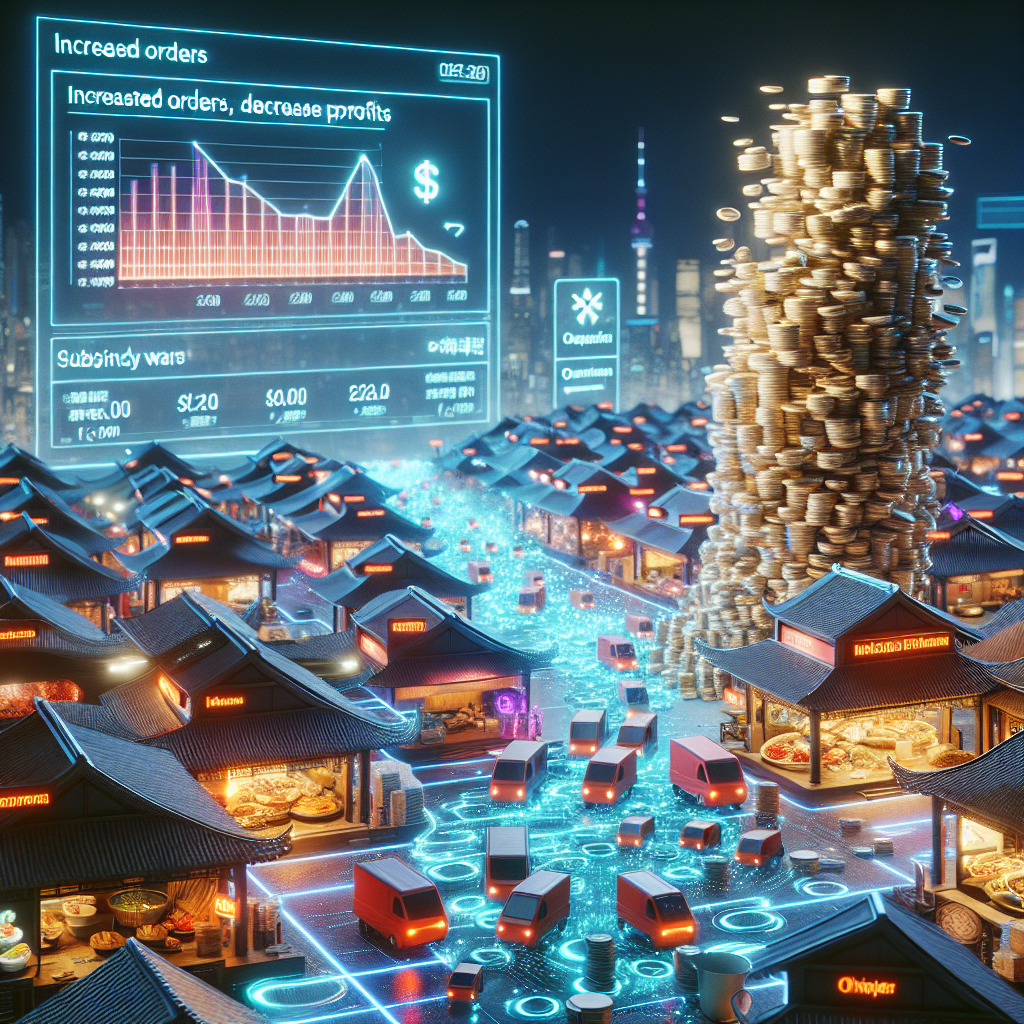

Since the beginning of 2025, intense subsidy wars have erupted among Chinese food delivery and instant e-commerce platforms, stimulating consumer demand and order growth, but leading to a structural crisis of “increased orders, decreased profits” for businesses. Financial reports and academic studies have revealed that behind the subsidy frenzy lies a phenomenon of “false prosperity,” exposing deep-rooted crises in the platforms, businesses, and the entire market structure.

The term “subsidy war” refers to fierce competitive behavior where multiple competitors, such as e-commerce platforms, offer substantial financial subsidies to capture market share or gain competitive advantages.

The latest quarterly financial reports reflect heavy financial pressures on Alibaba, JD.com, and Meituan, the three major e-commerce platforms in China.

On November 25th, Alibaba announced its third-quarter financial report, with adjusted profits plummeting by 72% year-on-year to approximately 10.4 billion RMB, far below market expectations.

Despite a 16% growth in revenue for Alibaba’s Chinese e-commerce business group after consolidating Taobao, Tmall, Ele.me, and Fliggy, sales and marketing expenses surged by 105% year-on-year, signaling high investment but insufficient returns in the food delivery sector.

E-commerce giant JD.com entered the food delivery market in February, sparking a price war with Meituan and Alibaba’s Ele.me. In April, Alibaba launched a local rapid delivery service called “Taobao Dash Purchase” and in July, initiated a 50 billion RMB (approximately 7 billion USD) subsidy program to boost its instant e-commerce business, including food delivery.

JD.com faced similar pressures, with a 14.9% increase in total revenue in the third quarter but a profit decline of over 50%. New businesses, including food delivery, incurred a quarterly loss of 15.736 billion RMB, accumulating a total loss of 31.8 billion RMB in the first three quarters, with continuous capital injection into the food delivery segment.

Meituan released its third-quarter financial report later that week, with a sharp 89% drop in net profit to only 1.493 billion RMB in the previous quarter. Analysts predict a potential loss for Meituan in the third quarter, with a net loss estimated at 13.8 billion RMB.

From 1 RMB milk tea, 0.01 RMB coffee, to Meituan’s “Good Food Group” offering a 6.9 RMB (approximately 0.97 USD) four-dish meal delivered within 27 minutes, major platforms are attracting consumers with low prices and fast delivery. In mid-September, the three major e-commerce platforms even opened pre-orders for the iPhone 17, promising delivery within 30 minutes, ushering in a new stage for instant e-commerce.

However, behind the intense stimulation of consumer demand from this subsidy frenzy, it reveals a deep-rooted crisis in the platform, business, and the entire market structure.

On November 21st, the School of Economics at Fudan University released a research report titled, “Earning Traffic, Losing Profit – How does the subsidy war affect food and beverage businesses?” Based on complete daily transaction data for over 40,000 food and beverage businesses for dine-in and delivery, the report clearly shows that businesses are facing a contradictory situation of “increased order volume but decreased revenue.”

The report indicates that since the intensification of the subsidy war in July, the daily total orders for “delivery + dine-in” for businesses have grown by an average of 7%, but the actual revenue has decreased by 4%. Assuming the profit margin for delivery remains constant, businesses have seen an average total profit decline of 8.9% since July.

The reason behind this is that although delivery orders have increased by nearly 20% on average since July, the actual revenue has also decreased by 20%, resulting in only a 0.5% increase in delivery revenue; dine-in orders and revenue have generally declined by over 10%. As the profit margin for dine-in is higher than delivery, this substitution of dine-in by delivery directly leads to a decrease in total profits for businesses.

Regarding this structural contradiction of “increased orders, decreased profits,” Professor Sun Guoxiang from the Department of International Affairs and Business at Nanhua University in Taiwan told Epoch Times that subsidies only bring “price stimulation, not value addition.”

He pointed out that many orders have low or even negative profit margins, and businesses not only have to comply with platform discounts (such as discounts for reaching a certain amount of consumption) and provide additional subsidies but also incur more promotion costs, ultimately resulting in a situation where “net income remains the same or even lower.”

Sun Guoxiang explained that the addition of delivery orders often only diverts dine-in customers, bringing “channel substitution” instead of channel growth, overall presenting a scenario of “false prosperity.”

He warned that intense platform competition under high subsidies will push the market towards “jungle law,” where the strong become stronger, the weak become weaker, chain brands gain more traffic, and independent stores become more vulnerable. The intensified platform monopoly reduces the bargaining power of businesses, and once subsidies are withdrawn, small stores may face a sudden contraction in orders or even closure.

Furthermore, subsidies causing a decrease in dine-in traffic also spill over to nearby commercial areas. Studies indicate that during periods of intensified competition, online reviews for leisure and entertainment businesses significantly decrease due to a diversion of traffic to food delivery services; the impact on beauty and essential service businesses is comparatively smaller.

Fudan University’s research shows that extensive subsidies put businesses in a dilemma: if they do not participate in subsidies, they will lose competitiveness and customers, but by participating, they have to bear additional costs, further compressing profits. This forces many businesses to adjust their operations strategy in a “passive participation” manner.

Sun Guoxiang reminded that platforms often prefer to allocate traffic and subsidies to chain brands, those with high ratings, high delivery efficiency, and willing to invest in promotion. Once the platform’s monopoly intensifies, it may unilaterally change the rules, leaving businesses with no counteracting power.

Different voices are also heard from the consumer end. A Beijing white-collar worker interviewed said that the high commissions and subsidy structures of platforms make businesses “completely the platform’s laborers.” Under long-term pressure, businesses are unable to invest in product quality but are forced to consider how to reduce costs.

He believes that this not only exposes issues in the entire food supply chain but also makes it more difficult for China’s existing physical economy to recover. “Even though it stimulates consumption, it results in businesses operating at a loss.”

The white-collar worker frankly stated that banks actively promoting consumer loans reflect the urgent need for rescue in the physical economy.

Fudan’s research also warned that “excessive low prices” disrupt the market pricing system, and conventional market mechanisms should ensure the independent pricing autonomy and reasonable profit space for small and medium-sized businesses.