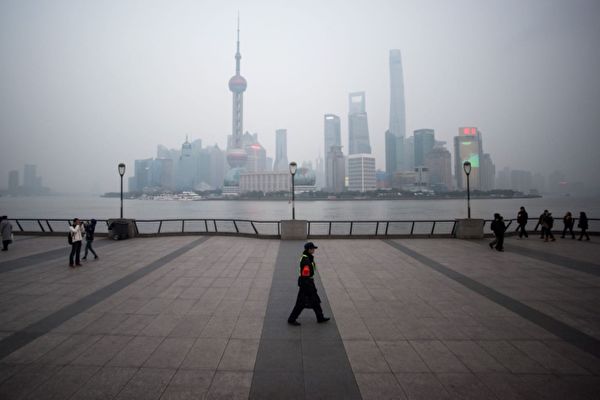

【Epoch Times December 8, 2025 News】Since the end of the pandemic lockdown on December 7, 2022, population outflow, foreign capital withdrawal, and corporate relocation have successively occurred in Shanghai, Beijing, as well as the Yangtze River Delta and the Pearl River Delta regions. The industrial capacity utilization rate on the Chinese mainland has decreased, urban vitality has declined, and resident consumption continues to drop. A resident in Shanghai lamented, “Shanghai feels like a ghost town.”

The emptiness of Shanghai is most apparent. Local residents told reporters on December 8 that three years after the end of the pandemic lockdown, the streets are unusually quiet. Except for Nanjing East Road and Yuyuan with visitors on holidays, most commercial areas have few pedestrians on regular days. Cafés have more empty tables, and the nighttime lights are not as bustling as before.

Ms. Liu, a resident in Pudong across the Huangpu River, expressed that she clearly feels the city’s pace has slowed down: “I used to see foreigners often, but now they are rare. The shopping malls and subways are also quiet.”

The Shimao Binjiang Garden in Pudong is a well-known luxury residential area. Mr. Wang, a homeowner there who used to be in business, shared that the property he bought for over 20 million yuan in 2015 rose to 50 million yuan in 2018 but has now dropped to less than 20 million yuan. He regretted, “If I had known, I should have sold the property as soon as the pandemic lockdown ended. There are many vacant houses now.”

He added that the most noticeable change is among the foreign residents in the community: “There used to be many foreigners living in our community, but now they have almost all left, and foreign companies have also relocated. Shanghai is becoming like a ghost town.”

Official data shows that Shanghai’s total permanent population decreased by more than 150,000 residents between 2024 and 2025; the office market is also under pressure, with a vacancy rate approaching 23% in the first quarter of 2025, much higher than before the pandemic.

In Xuhui District, rental prices for Grade A office buildings have been continuously declining in recent years. Businessman Li Qiang disclosed that rental prices for his three properties in Xuhui have significantly dropped with no takers: “My properties are Grade A office buildings, with rents around 8 yuan per square meter before, now even bargaining for 5 yuan, but still no takers.”

Market data indicates that the rental price for Grade A office buildings in Xuhui District currently ranges from 5.5 to 6.5 yuan per square meter per day, translating to 165 to 195 yuan per month. Industry insiders point out that due to the continuous increase in new supply in areas like Xujiahui, Huaihai Road, and Xuhui riverside, the vacancy rate is rising, and rental prices are being pushed down.

Many business executives believe that the withdrawal and relocation of foreign companies are changing the business landscape of Shanghai.

Li Qiang, who has long cooperated with foreign enterprises, noted that the presence of foreign companies in Shanghai has significantly decreased over the past two years: “Several of my German business friends said their companies have relocated their headquarters to Singapore, and companies from France, South Korea have also left. Even the government did not expect foreign companies to leave so quickly after the pandemic restrictions were lifted.”

Public data also confirms his observations. According to Colliers International’s third-quarter report this year, the vacancy rate for Grade A office buildings in Shanghai has risen to about 21.4%, with average rents down by 3.3% from the previous quarter. Savills’ quarterly statistics also show a continued decline in rental prices and an increase in vacancy rates for Grade A office buildings in Shanghai in the first quarter of 2025. Industry data indicates that Grade A office rents in Shanghai have been declining for more than ten consecutive quarters since 2022, with new supply far exceeding net absorption, leading to a continuous imbalance between supply and demand.

Li Qiang remarked, “I used to have dinner with my foreign enterprise friends on weekends, but many have already left China. Once the company headquarters move, entire floors of office space remain empty.”

In the Yangtze River Delta region, the speed of capacity relocation in Jiangsu and Zhejiang has significantly increased. Suzhou, Kunshan, Wuxi, and other areas continue to see a slowdown in industrial growth, with many foreign electronic companies relocating their assembly lines to Cambodia, Vietnam, and Thailand, while retaining only research, engineering, and administrative functions locally. In Zhejiang, Yiwu, Ningbo, Wenzhou have also moved a large number of production processes of shoes, clothing, hardware, and daily necessities to Southeast Asia to reduce risks and costs.

An executive in a foreign enterprise in Suzhou, Ms. Gu Shen, mentioned to the reporter, “Labor costs are just one factor, the greater pressure comes from customer demand for diversified production bases. The proven production bases in Southeast Asia make them feel more secure.”

Gu Shen indicated that in the manufacturing industry along the coast in China, Nantong is highly concentrated in textiles, Anhui is a center for clothing and small home appliance parts production, and Henan also has a part of the manufacturing chain that is relocating externally: “I heard in recent years, the textile industry in Nantong, clothing and small home appliance parts in Anhui, and some manufacturing in Henan have moved to Cambodia, Vietnam, and Southeast Asia.”

Compared to the Yangtze River Delta region, the Pearl River Delta manufacturing chain is also experiencing a wave of relocation. Dongguan, known as the “world’s factory” for many years, has not seen several manufacturing categories restore their pre-pandemic capacity levels between 2024 and 2025. Many processing and trade companies have shifted their production lines to Boleangdan in Cambodia and Beizhuan in Vietnam. The industrial area’s nighttime illumination rate has decreased, and the labor market has cooled down.

Mr. Gong, a former manager at an electronics factory in Dongguan, stated that after the pandemic lockdown ended, many business people truly realized that China’s economy was rapidly declining, with factory closures and increasing unemployment: “The number of factories closed in the past two years exceeds those of the previous decade combined. The international large-scale enterprises that recently exited were all deeply affected by the shift in the supply chain and found it difficult to continue.”

In recent years, many multinational companies have adjusted their layouts in China, including Dell, Microsoft, Stanley Black & Decker, and some consumer goods and manufacturing companies. Mr. Gong remarked: “They are all either downsizing the workforce, scaling back production, or transferring the supply chain to other regions.” Research institutions have pointed out that foreign operation in China is contracting, with increasing cases of manufacturing and technology companies withdrawing.

In Guangzhou, the downsizing of foreign investment is also accelerating. Japanese automotive, home appliance, and electronics manufacturers are shrinking their market departments in China, and many supply chain companies are adjusting their production layouts in China. Mitsubishi, Honda, and Komatsu announced reductions or exits from some business sectors in China between 2024 and 2025. Signs of contraction are also appearing in the related industrial chains in Shenzhen and Guangdong, with some Japanese-owned automotive parts companies reducing their production and sales scales in China.

On the contrary, the international business atmosphere in Beijing, the capital, has also cooled down. In the first quarter of 2025, the vacancy rate for Grade A office buildings in Beijing reached nearly 12%, with a sharp decrease in the number of foreigners in Sanlitun and Wangjing compared to before the pandemic, causing the international community to be less active.

Mr. Li, a retired civil servant who recently returned to Beijing from Shanghai, introduced, “Beijing is not doing well either. A few days ago, I noticed a decrease in the number of passengers as soon as I got off the plane. There are very few foreigners in Wangjing now. Several foreign enterprises that I am familiar with have their floors empty.”

Mr. Li mentioned that since early 2023, house prices in mainland China have rapidly declined, corporate profits have sharply decreased, and local fiscal self-sufficiency rates have fallen. Some provinces increasingly rely on transfer payments to maintain basic expenditures: “The scale of infrastructure investment in my son’s unit has come to a stop, and they will soon merge with other state-owned enterprises. Who would have thought that the environment after the pandemic lockdown would be so poor.”

Yan Li, an academic researcher in Beijing specializing in global supply chains, pointed out during the interview that what China is facing is not the lingering impact of the pandemic but an accelerated period of structural downturn caused by the centralized system. He believes that the relocation of production capacity, reduced foreign investment, and supply chain reorganization are causing China to gradually lose its central position, and will face even stronger competitive pressure in the future.