80-year-old dissident Dong Hongyi recently sued the Handan City Government and its Social Insurance Administration for suspending and deducting over 70,000 yuan of his pension during his imprisonment, questioning the lack of clear legal basis and alleged violation of higher laws and legislative procedures. This administrative lawsuit, which was recently heard by the Handan City Congtai District Court, has drawn significant attention.

According to court documents provided by Dong Hongyi to The Epoch Times and legal experts, this case not only involves the property rights protection of individual retirees but also touches on a systemic controversy prevalent in China in recent years – whether inmates should have their pensions suspended and whether administrative authorities can limit citizens’ social insurance rights based on departmental normative documents.

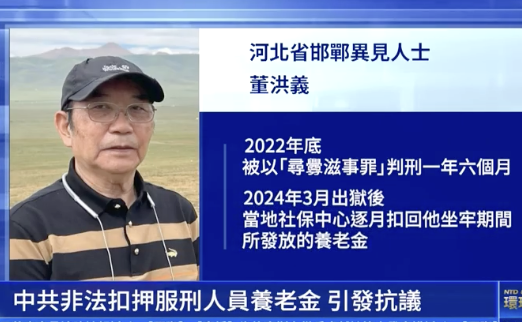

Dong Hongyi was sentenced to one year and six months in prison for “provoking trouble” at the end of 2022 and was released in March 2024 after serving his term. Subsequently, the local social security department began monthly deductions from his pension received during his imprisonment, amounting to a total of 76,482.44 yuan.

Dong Hongyi believes that his pension is personal property formed by lawfully paying social insurance premiums during his employment period, and it should be protected by the Constitution, Labor Law, Social Insurance Law, and Law on the Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly. “Imprisonment” itself is not a legal reason for depriving or restricting pension benefits.

During the court hearing, the defendant, Handan City Government, argued that the suspension of the pension was an “administrative confirmation action” based on the fact of imprisonment, not an administrative penalty, thus the procedural requirements of the Administrative Penalty Law do not apply.

In response, Dong Hongyi argued in court that Article 2 of the Administrative Penalty Law clearly stipulates that any act that “punishes by reducing rights” constitutes an administrative penalty. The suspension and deduction of his pension directly resulted in property rights loss, possessing a clear punitive nature, and categorizing it as administrative confirmation is “logically and legally untenable.”

The core dispute of this case revolves around a reply letter from the State Council’s Labor and Social Security Department concerning the issue of pension benefits of retirees being sentenced after the release of the “44th Document” in 2001. The document states that retirees sentenced to imprisonment or more severe penalties should have their basic pensions suspended during their imprisonment.

Dong Hongyi pointed out that this document is merely a reply letter from the department’s office, not a law, administrative regulation, or a departmental regulation established through lawful authorization. It substantially impairs citizens’ property rights and violates Article 91 of the Legislation Law that prohibits setting norms that diminish citizens’ rights without a legal basis.

Furthermore, the document issued in 2001 has already surpassed 20 years, making it an “expired and ineffective” document according to the law, as the drafting agency has never extended its validity in accordance with the law.

In addition to the 44th Document, in 2012, the Communist Party’s Organization Department and two other departments issued a document numbered “69” in secret. Several insiders revealed that this document serves as a key basis for practical implementation in various regions, but in the administrative defense statement, it was explicitly marked as “not for public release” citing “sensitive issues.”

Legal expert Wang Ming (a pseudonym) analyzed for The Epoch Times, saying that although some local websites claim to have released it, the document itself explicitly states it is confidential and not public. This indicates that from the perspective of legal effectiveness and normative documents, it is an internal document and is invalid for external use. Despite local publication, attempts to legalize it would still fail.

Insider Qin Yi bluntly stated that “non-public documents cannot be enforced as valid legal documents, but in reality, they are enforced.” He pointed out that this “say one thing, do another” governance model has become a systemic issue eroding the foundation of the rule of law and leading to a highly opaque operation of administrative power.

Another insider, Wang Yong, noted that the provisions in the 69th Document are vague, lacking clear interfaces with relevant laws such as the Labor Law and Social Insurance Law, with many parts ambiguously phrased as “handled at discretion,” thus lacking precise standards.

The document also references the “labor education” system, which was abolished in 2013, while the document indicates implementation from September 1, 2012, continuing to reference a soon-to-be abolished system, posing a legal issue concerning its applicability.

After the court hearing on December 16, Dong Hongyi submitted supplemental remarks to the court on December 19, formally requesting a legal and reasonable review of the above-mentioned three administrative documents presented by the defendant Handan City Government – the “reply letter,” the “supplementary explanatory letter,” and the “notice,” and demanded evidence from the government to prove whether these three documents were authorized by the National People’s Congress, the Standing Committee of the People’s Congress, or the State Council.

Citing Articles 12 to 15 of the Legislation Law, Dong Hongyi pointed out that even if there is authorization, matters related to crimes and penalties fall within the clearly prohibited range of authorized legislation, with the authorization period not exceeding five years, and the authorized agency cannot further delegate its authority.

In principle, an excessively long authorization period is tantamount to replacing formal laws, and the prohibition on delegating authority aims to prevent arbitrary expansion of special powers granted to legislative institutions by administrative departments, preventing power abuse or unclear accountability.

Furthermore, from a criminal law perspective, Dong Hongyi argued that the primary and additional penalties listed in Articles 32 to 34 of the Criminal Law do not include provisions for “deprivation or suspension of pensions.” The effective judgment did not declare the deprivation of relevant rights, and the social security department subsequently imposed additional penalties, violating the principles of legality and proportionality in criminal punishments.

In his supplementary opinion, Dong Hongyi also expressed from a humanitarian perspective that suspending the pension put him “in dire straits.” He told The Epoch Times: “Those affected are people in their sixties, seventies, and eighties. Today, I am eighty years old. Having the pension deducted while serving a sentence is inhumane, lacking in humanity.”

He believed that such actions completely contradict the principle of “not deducting pensions” as stipulated in the Law on the Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly and create a stark contrast with the official claims of “governing the country according to law” and “protecting the rights of the elderly.”

Dong Hongyi stated unequivocally that he will continue to pursue litigation: “We will follow through all the way. If we lose the case in the Congtai District Court, we will appeal to the Intermediate Court. If the Intermediate Court fails, we will go to the Higher Court of Hebei Province, then to the Supreme Court of the country. We will persist until the end.”

Former Secretary-General of the “Chinese Human Rights Watch” Xu Qin, who was released over five months ago, was similarly asked to return a pension of 150,000 yuan received during his imprisonment. The local social security bureau cited the “44th Document” to justify their actions.

Legal experts pointed out that the social security department’s cancellation of pension funds, considered their personal property, effectively constitutes a criminal property punishment, indicating that the social security department does not possess such rights and lacks legal basis.

They generally believe that whether it is an administrative enforcement of “suspension” or an administrative measure of “temporary suspension,” as mentioned earlier, due to a lack of substantive legal basis, irrespective of procedural flawlessness, it constitutes illegal or even criminal behavior.

Article 64(2) of the Social Insurance Law of the People’s Republic of China explicitly states that “social insurance funds are earmarked for special purposes, and no organization or individual may embezzle or divert them.”

As of the time of writing, the Congtai District Court has not issued a first-instance judgment. Dong Hongyi has made it clear that regardless of the outcome, he will continue to appeal to the Higher People’s Court of Hebei Province, and even to the Supreme Court, “persisting until the end.”