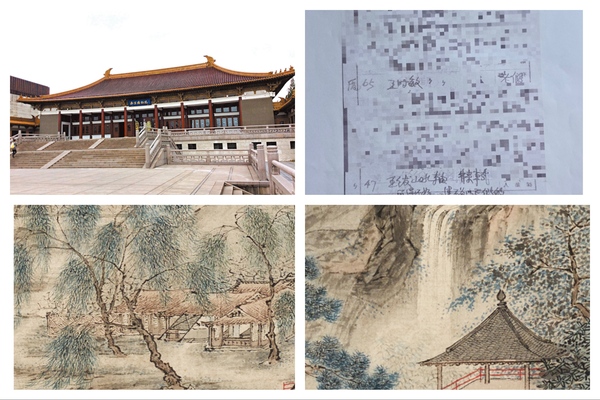

On December 17th, 2025, Chinese media outlet “The Paper” exclusively published an article titled “Why did the Ming Dynasty painting ‘Jiangnan Chun’ by Qiu Ying from the Nanjing Museum appear in the auction market?”, which immediately put the Nanjing Museum in the spotlight. The museum responded on the same day, stating that they will verify the whereabouts of 5 paintings including “Jiangnan Chun”.

The Nanjing Museum issued a statement on December 17, 2025, regarding the media coverage of the Ming Dynasty masterpiece by Qiu Ying in their collection appearing in the auction market, sparking public attention.

Since November 2024, the museum has received court documents twice regarding the “donation contract dispute” of Ms. Pang Shuling and has conducted investigations to verify the claims.

In January 1959, the museum officially received 137 paintings donated by Mr. Pang Zenghe (father of Pang Shuling). The 5 controversial paintings mentioned in the report were appraised as “false” by an expert group consisting of Zhang Heng, Han Shen, and Xie Zhiliu in 1961, and again in 1964 by the expert group composed of Wang Dunhua, Xu Yunqiu, and Xu Xinnong. In the 1990s, the museum disposed of these 5 paintings. The case is currently under review.

The Nanjing Museum will cooperate with the case investigation to verify the whereabouts of the 5 paintings. If any illegal activities are found during the disposal process, they will cooperate with relevant departments to handle the matter in accordance with the law. They also plan to strengthen the regulations on donated items and museum collections.

The Nanjing Museum, a large historical and art museum, is one of China’s national first-level museums, alongside the Beijing Palace Museum and the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

Pang Laichen (1864—1949) was a renowned collector of modern and contemporary China, known for the exquisite quality and completeness of his collection of historical paintings at “Xu Zhai.” In 1959, descendants of Pang Laichen donated a large number of precious ancient paintings to several state-owned cultural heritage institutions, with the Nanjing Museum receiving the most, including the national first-level cultural relics, the Ming Dynasty “Jiangnan Chun” by Qiu Ying.

However, the question of whether the descendants of Pang Laichen donated the artworks or they were forcibly taken by the Chinese Communist Party remains a subject of concern.

Pang Shuling, granddaughter of Pang Laichen, revealed that in 1953, then Director of the National Cultural Relics Bureau, Zheng Zhenduo, wrote a letter to Xu Senyu, Chairman of the Shanghai Cultural Relics Management Committee, listing “Jiangnan Chun” as an essential item for collections. “At that time, the Nanjing Museum requested donations from us. The 137 pieces of cultural relics, including precious artworks from the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, were donated to them free of charge…”

In recent years, Pang Shuling discovered through reports provided by the Nanjing Museum that the national first-level cultural relic, the Ming Dynasty “Jiangnan Chun” by Qiu Ying, donated by the Pang family to the Nanjing Museum was purchased by Lu Ting and Ding Weiwen at the Nanjing Yilanqiao in the 1990s, with the establishment of Nanjing Yilanqiao registered in December 1996.

Following this, the Pang family began writing letters to the Nanjing Museum, hoping to inspect the current status of the 137 pieces of donated treasures from 1959. “This is the effort of our ancestors. As descendants, it is our duty to be concerned and have the right to know if they have been properly preserved,” said Pang Shuling. “The Nanjing Museum has never responded to us and has always ignored me.” This silence has persisted for years.

On October 10, 2024, Pang Shuling officially filed a lawsuit, demanding that the Nanjing Museum fulfill its duty to inform the Pang family about the donated cultural relics.

During the court hearing, the Nanjing Museum questioned Pang Shuling’s lawsuit eligibility, citing that she was not the donor herself. The case ultimately ended with mediation, with the Xuanwu District Court in Nanjing requiring the Nanjing Museum to allow Pang Shuling to inspect all donated relics by June 30, 2025, and explain the whereabouts of missing relics.

However, just before the scheduled inspection date, a dramatic scene unfolded.

“Before we could go and see them, we suddenly learned that in the spring auction catalog of a Beijing auction company in May, the Ming Dynasty artwork ‘Jiangnan Chun’ by Qiu Ying was prominently featured! Starting at 88 million yuan!” said Pang Shuling, expressing the feeling of finally finding something after searching everywhere.

After Pang Shuling reported the incident, the auction company withdrew the item from the auction.

An anonymous art market expert told “The Paper” that the art market was not very prosperous at the moment. The appearance of the Ming Dynasty “Jiangnan Chun” by Qiu Ying in the auction market caused a great stir, with the auction company starting the bidding at 88 million yuan. “The artistic value of this masterpiece is recognized, and with its history, we estimated it would easily reach over a hundred million in the auction. It was wise for the auction company to withdraw it after realizing it originally came from the Nanjing Museum.”

By the end of June 2025, Pang Shuling walked into the storage room of the Nanjing Museum as agreed in the mediation document. Out of the listed 137 pieces, she only saw 132; 5 were unaccounted for.

In addition to the Ming Dynasty “Jiangnan Chun” by Qiu Ying, there were also artworks including the Northern Song Zhao Guangfu’s “Double Horse Painting Scroll,” the Ming Dynasty Wang Fu’s “Song Breeze Xiao Temple Painting Scroll,” the Qing Dynasty Wang Shimin’s “Imitation of Beiyuan Landscape Scroll,” and the Qing Dynasty Tang Yifen’s “Color Landscape Scroll.”

Shortly after the inspection, the Nanjing Museum responded in writing, stating that these 5 paintings were identified as “counterfeit” and have been “removed” from the collection sequence, undergoing “transfer and adjustment” processing.

Pang Shuling said, “My great-grandfather Pang Laichen’s collection was widely recognized during his lifetime. The items donated to the country were carefully selected treasures. Even if there were academic disputes, to decide that they are ‘forgeries’ is a significant matter. Why were the donors not informed? Where is the common appraisal and confirmation process? They handled it without any clear explanation, and even the most valuable piece was sent to an auction. How are we supposed to understand and accept this?”

On November 20, Pang Shuling filed a lawsuit against the Nanjing Museum in the Xuanwu District Court in Nanjing. The core demand of Pang Shuling is for the Nanjing Museum to clarify the exact whereabouts of the Ming Dynasty “Jiangnan Chun” by Qiu Ying and the other four missing ancient paintings that were “transferred and adjusted” at the museum, ultimately for their return.

In an effort to prove the legality of their disposal, the Nanjing Museum submitted two appraisal materials to the court, one being the appraisal opinions record (copy) from 1961 and the inventory appraisal opinions record for paintings in July 1964.

Pang Shuling said, “One of the appraisers listed on the appraisal document, Wang Dunhua and Xu Yunqiu, were actually Nanjing Museum staff. Xu Yunqiu was involved in collecting works, not an expert in painting and calligraphy appraisal!”

The presentation of these two pieces of evidence sparked controversy in court. Pang Shuling recalled that most of the records were heavily redacted, with only scattered mentions of “Qiu Ying’s ‘Jiangnan Chun’ forgery” visible. Specific details on how the experts determined the paintings as “fakes” based on what criteria were not shown in the record, and the Nanjing Museum did not provide further clarification in court.

Due to the Nanjing Museum’s failure to provide substantial evidence on the whereabouts of the artworks, no substantial mediation was reached in court. On December 16, 2025, Pang Shuling signed a “Application for Compulsory Enforcement”, formally requesting the Nanjing Museum to provide detailed information on the whereabouts of the above five items.

It is worth noting that ten years ago, the Nanjing Museum held a “World of Collections: Pontings’s Xu Zhai Ming and Qing Masterpieces Exhibition,” showcasing 200 pieces of Ponting’s collection, ranging from Song Emperor Huizong Zhao Ji to the Southern Song Four Greats and Yuan Four Greats. At that time, the Nanjing Museum highly praised Ponting and his Xu Zhai collection, acknowledging its orderly heritage and rigorous identification.

Wang Qizhi, then Vice Director of the Nanjing Museum, stated during the 2015 “Pontings’s Xu Zhai Ming and Qing Masterpieces Exhibition Symposium” that the Xu Zhai collection at the museum was their most precious collection of paintings and calligraphy.

Comparing this with today, where the Nanjing Museum presented a significant portion of Ponting’s collection as forgeries in court, Pang Shuling finds it unbelievable.

Pang Shuling told “The Paper,” “The key issue is that during the court hearing, the Nanjing Museum did not provide a clear explanation about the specific whereabouts of the Ming Dynasty ‘Jiangnan Chun’ and the other four ancient paintings that were ‘transferred and adjusted.’ How did a painting previously labeled as a ‘forgery,’ the ‘Jiangnan Chun’ by Qiu Ying, show up in a well-known Beijing auction company’s spring auction catalog in 2025? Where did the remaining four paintings end up? These questions remain a mystery in court.”

“If the Nanjing Museum believes that the ancient paintings donated by the Pang family are forgeries, they should have notified the Pang family members immediately, rather than handling it without their knowledge,” said Yin Zhijun, a lawyer from Beijing Gao Si Law Firm, in an interview with “The Paper.” “If they confirm it as a forgery and decide not to keep it, they should return it to the Pang family.”

“The donation from the Pang family spans over half a century, this dispute not only concerns the ownership of several artifacts but also impacts the public’s trust in the system of donating cultural relics,” commented a senior figure in the cultural relics field.

Pang Shuling believes that the lifelong effort and collection of her great-grandfather Pang Laichen should not have ended up at an auction house from the Nanjing Museum. “Moreover, the Nanjing Museum’s assertion that the works are ‘forgeries’ may just be an excuse. What we need to understand is why national treasures collected by the Nanjing Museum ended up in the art market. Is it due to mismanagement? This severely undermines the trust in donations.”

Previously, regarding the Ming Dynasty “Jiangnan Chun” by Qiu Ying from the Nanjing Museum appearing in the auction market, “The Paper” attempted but failed to secure interviews.

At the time of the publication by “The Paper,” the Nanjing Museum’s official website still listed the Pang family donated artworks as their “most precious paintings and calligraphy collection.” However, the Nanjing Museum has yet to provide an explanation about how the Ming Dynasty “Jiangnan Chun” by Qiu Ying from the Pang family donations ended up at the auction, the disappearance of the 4 additional ancient paintings, and the contradictions in their handling.

“The Paper’s” report has stirred widespread attention online.

Netizens expressed their opinions, “On December 17, the Nanjing Museum stated they would ‘verify the whereabouts of the artworks and handle any violations seriously,’ but failed to address the core questions: why they did not inform the donors, failed to prove that the auctioned artwork and the museum collection are not the same, and avoided responsibility for the handling in the 1990s. The essence of the event has surpassed the individual case: how state-owned cultural heritage institutions balance cultural heritage management rights with public supervision has become a severe test for the cultural heritage protection system.”

“This response is full of loopholes. If the artworks were donated by others and deemed fake, why not return them to the donor? An institution like the museum should return the paintings recognized as fake, and provide them with documentation. Even for everyday attendance records, signatures and procedures are required, let alone for invaluable artworks. The absence of processes and written certificates is troubling.”

“It’s strange. The Nanjing Museum did not mention how the identified fake paintings were dealt with. According to the law, if you recognize them as fake and they should not be in the collection, you should return them to the donor. How did they end up in someone else’s hands and even sent to an auction?”

“Regardless of whether the paintings are real or fake, how could the disposed paintings end up at an auction, selling at a high price? A proper investigation is needed, with a clear explanation. They really need to thoroughly investigate the museum’s collection; otherwise, the most precious heritage might be sold off.”

“A Ming Dynasty ‘Jiangnan Chun’ by Qiu Ying, with an estimated value of 88 million yuan, disappeared from the Nanjing Museum collection and reappeared in the auction market, raising questions about the management flaws in state-owned cultural institutions.”

“If they sold a fake, someone might end up in jail. If it’s a forgery, it should be returned. Chinese museums should conduct a comprehensive inventory, re-registering all artifacts.”

“The Paper” has indeed delivered a major news story this time. If the report is accurate, the Nanjing Museum’s longstanding reputation has been tarnished. The Nanjing Museum, one of China’s three major museums, formerly known as the National Central Museum founded in 1933 by Cai Yuanpei and others, was the first museum established in China and the first large comprehensive museum built with national investment.