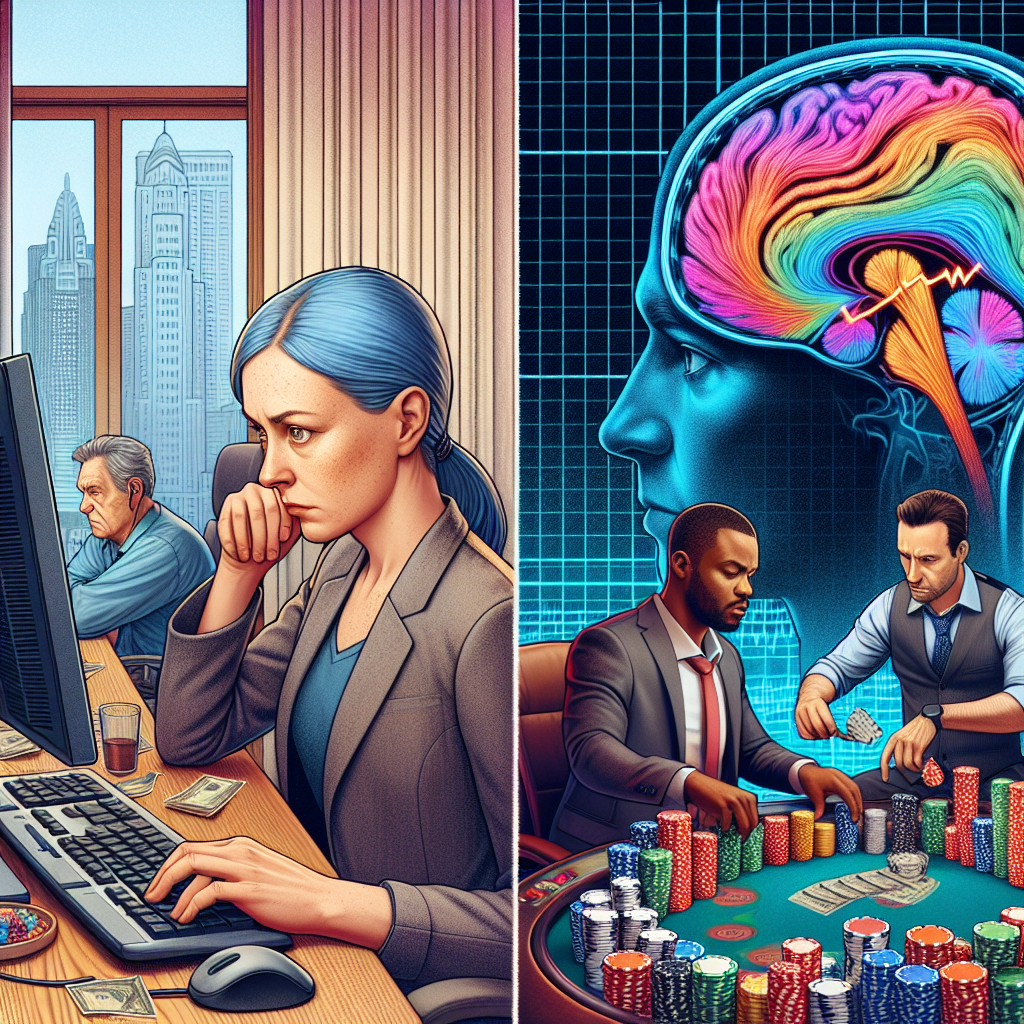

【Epoch Times News, November 17, 2025】When Wall Street traders anxiously stare at the declining curves on their screens, their brain responses are not much different from a gambler’s calmness at a casino table. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies show that during moments of intense market volatility or high-risk decision-making, the amygdala in the brain, which governs fear and anxiety, is activated first, while the prefrontal cortex responsible for rational analysis and long-term planning often reacts later.

This phenomenon is at the core of what “Neuroeconomics” focuses on – when humans make decisions, they are not the “Homo economicus” who calmly calculates risks and rewards, but rather a complex system woven from emotions, neural activities, and memory. Every instance of consumption, investment, or negotiation is actually a struggle between brain emotions and rationality in milliseconds.

Neuroeconomics emerged in the late 1990s to early 2000s as a new interdisciplinary field that integrates neuroscience, psychology, and behavioral economics. It seeks to answer a seemingly simple yet challenging question: when humans make economic decisions, how does the brain evaluate “value,” balance “risk,” and make choices between emotions and rationality?

The rise of this discipline has two backgrounds. First, behavioral economics challenges the assumption of the “economic man,” revealing that human decision-making is often influenced by emotions and psychological biases. Second, breakthroughs in neuroscience technologies allow researchers to directly observe brain activity during decision-making processes through fMRI and electroencephalography (EEG), linking “economic behavior” with “neural mechanisms” for the first time.

New York University scholar Paul Glimcher is considered one of the founding figures. He introduced the concept of “Neurobiology of Value,” proposing that the brain converts subjective value into action signals through specific neural networks, explaining how humans make choices at the neural level.

At the same time, neuroscientist Antonio Damasio in his work “Descartes’ Error” stated: emotions are not the enemy of rationality, but the foundation of rationality. His research on patients with prefrontal lobe damage found that while they could engage in logical reasoning, they couldn’t make practical decisions, revealing the key role of emotions in rational judgment.

Research in neuroeconomics gradually outlines a “decision map” – how different brain regions cooperate in each choice, shaping people’s behavioral patterns.

Prefrontal Cortex: Rational analysis, long-term planning; inhibiting impulses, balancing risk and reward;

Nucleus Accumbens: Dopamine reward center; activated when anticipating profit, driving risky and speculative behavior;

Amygdala: Fear and risk perception; amplifying negative messages, intensifying panic decisions;

Insula: Disgust and loss sensation; triggering strong emotional reactions to losses, prompting avoidance behavior.

Experimental research shows that when people face high-risk options with potential high returns, the nucleus accumbens, the core region in the brain responsible for reward processing, is notably activated. This region is closely associated with dopamine release, where neural activity increases when anticipating rewards, leading individuals to experience excitement and impulsiveness akin to “taking a gamble.”

On the behavioral level, this “anticipatory reward response” often amplifies people’s risk preferences, making investors more inclined to take aggressive actions when faced with uncertain but attractive rewards.

During bull markets or periods of sustained asset price increases, investors’ expectations of future profits alone can activate the brain’s reward system. Several studies in neuroeconomics found that the activity levels of the nucleus accumbens in anticipating monetary returns are positively correlated with individuals’ risk-taking tendencies. Based on this, some neurofinance researchers speculate that, during market uptrends, dopamine release induced by expected profits may enhance investors’ pleasure and motivation, prompting them to continue buying. When this reward loop is collectively amplified at the group level, the market can form a “momentum effect” or even bubble psychology – a collective behavior driven by neural reward mechanisms.

Conversely, when potential losses emerge, the brain’s anterior insula quickly activates, emitting neural signals associated with disgust and withdrawal, prompting individuals to avoid risks. This response forms the physiological basis of “loss aversion” – even when the expected values of two options are the same, people tend to avoid losses.

This result echoes Nobel Prize-winning economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s 1979 “Prospect Theory” – they found that people’s subjective response to losses is about twice as strong as the pleasure from equivalent gains.

Looking at this “decision map,” we see the neurological roots of market frenzy and panic: during asset bubble periods, the activity in the nucleus accumbens is excessively strong, while the amygdala, responsible for vigilance and fear, responds slowly. The result is that the brain’s reward system gains the upper hand, and risk warnings temporarily malfunction – investors collectively fall into a “rational short-circuit.”

Therefore, neuroeconomics not only provides experimental support for behavioral finance, but also expands the term “irrationality” from the psychological level to the neural level.

Neuroeconomics has moved beyond theoretical deductions in the laboratory and quietly infiltrated the fields of financial markets, marketing strategies, and even public policies.

In the investment field, an increasing number of asset management institutions are beginning to introduce technologies such as brainwave and eye-tracking to quantify traders’ emotional fluctuations and decision biases in high-pressure environments. Experiments show that when market prices fluctuate drastically, traders’ left prefrontal lobe brainwave activity significantly changes, indicating that emotional disturbances and misjudgments of risk often occur simultaneously in extreme situations.

At the same time, more experiments demonstrate that meditation training can enhance the prefrontal lobe’s ability to regulate emotions, reduce the amygdala’s overreaction, thereby maintaining decision stability in high-stress environments.

In the marketing field, “Neuromarketing” has become a popular application. A research team at Baylor College of Medicine in the U.S. once revealed the neural mechanisms of brand effects through a blind taste test between Coca-Cola and Pepsi. When participants were unaware of the brand and based their evaluations solely on taste, most preferred Pepsi; but when the brand names were revealed, their preferences immediately shifted to Coca-Cola.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging scans show that brand cues activate the hippocampus associated with emotional memory and the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex related to value judgments, indicating that brand information can alter the brain’s value calculation. In other words, brand operation is not just a sensory experience but also creates a “brand imprint” at the neural level.

In the field of public policy, the combination of neuroeconomics and behavioral economics is influencing institutional design. Taking the U.S. retirement system as an example, the Auto-Enrollment mechanism arises from behavioral economics research on “inertia and status quo bias.” Neuroeconomics research further reveals the neural basis of this “inertial decision-making”: immediate rewards activate the marginal system, while delayed decisions rely on the self-control loop of the prefrontal lobe and basal ganglia. Policy design transforms “non-choice” into “automatic selection,” effectively utilizing the brain’s response mechanism of inertia to increase participation rates, becoming a representative application of neuroeconomics transitioning from the laboratory to public policy.

The emergence of neuroeconomics brings economics back from abstract theoretical curves to a real world filled with warmth and emotions. It reveals that every human choice is not purely based on rational calculations but is the result shaped by memory, emotions, and expectations. The brain is not a “perfect computer” in market models but more like an experiment pulled by dopamine, fear, and hope.

In an era dominated by artificial intelligence, algorithms, and quantitative trading, rationality seems to be redefined as “faster computation, more accurate predictions.” However, neuroeconomics reminds people that true insight may not lie in the data itself but in understanding how humans find order in irrationality – how they maintain judgment and choice amidst anxiety, greed, and uncertainty.

Neuroeconomics does not overturn the rational assumptions of economics but complements it with the other half that was overlooked – that rationality does not exclude emotional thinking but rather maintains judgment under the influence of emotions.