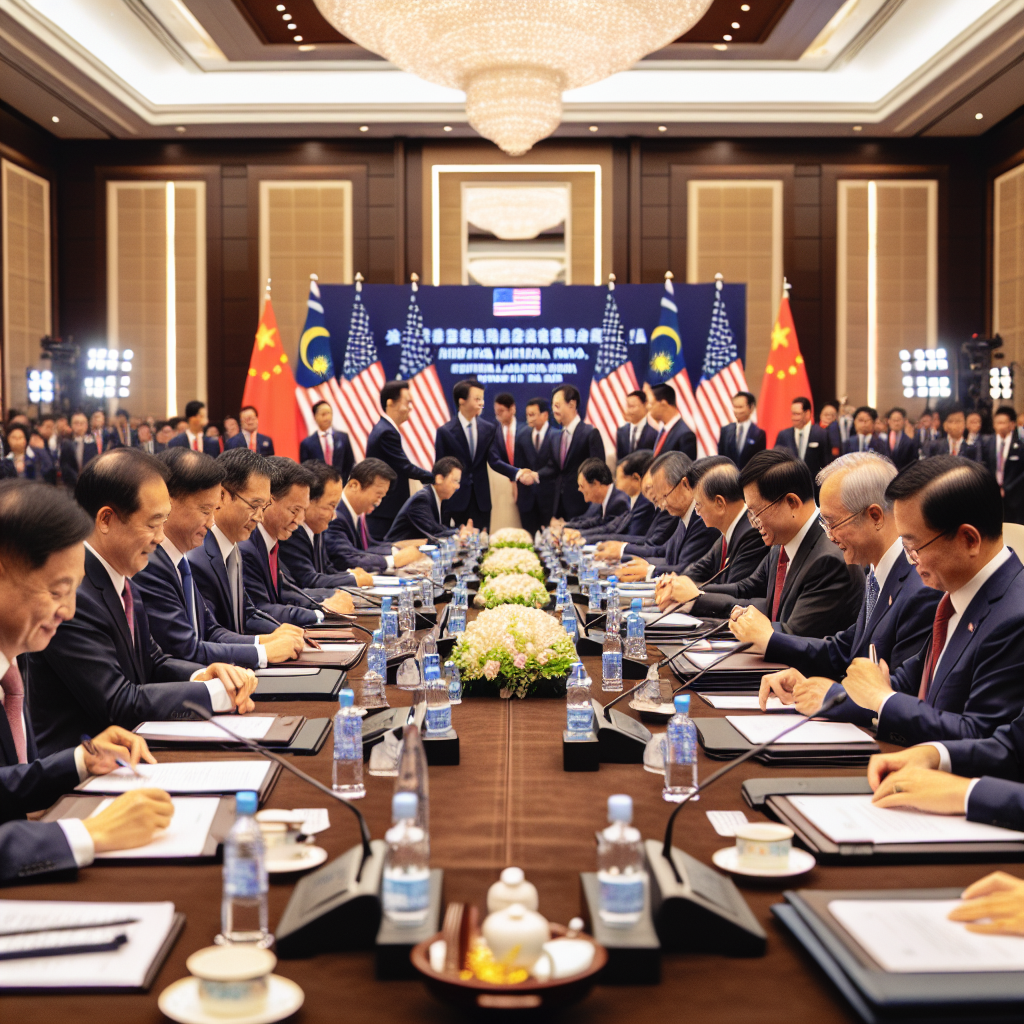

On October 26, the US-China economic and trade team wrapped up a two-day trade negotiation in Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia. The two sides reached a framework trade agreement, awaiting finalization during the meeting between US President Trump and Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping on October 30. However, analysts believe that due to the structural confrontation between the US and China, any agreements reached are unlikely to be long-lasting.

After the US-China trade negotiations, Robert Lighthizer stated that “I think we’ve put together a very successful (trade agreement) framework for the discussion of our two leaders on Thursday (October 30).” The framework agreement will prevent the US from imposing 100% tariffs on Chinese goods, while China will postpone implementing rare earth export controls and increase purchases of US soybeans.

Chinese trade representative Li Chenggang stated that both sides reached “preliminary consensus” on several significant economic and trade issues, with the next step being to go through their respective domestic approval processes.

The White House announced that Trump and Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping will meet on October 30 in South Korea, although Beijing has not yet publicly confirmed this arrangement. Trump last week stated that the agreement must be fair.

American University of Saint Thomas international research lecturer Yip Yaoyuan told Dajiyuan that China’s domestic economy is struggling, as Trump’s proposal of 100% tariffs would lead to the collapse of China’s internal market if no negotiations are made and no concessions are offered. Xi Jinping will have to make concessions, but they may be only superficial.

Despite seeming to have reached a framework agreement, it is not guaranteed that any agreements between the US and China will be long-lasting. China has a history of backtracking on agreements, as seen in the US-China trade deal during Trump’s first term where China did not comply with the terms. Rare earths and soybeans have been used as bargaining chips by China repeatedly.

Economic scholar Davy Jun Huang in the US told Dajiyuan that any framework-style trade agreements between the US and China at present are only temporary and not institutional arrangements. He believes that the systematic differences in politics, ideologies, legal systems, and industrial strategies between the US and China make the agreements fragile in terms of implementation and verification, especially given the high level of uncertainty in both countries’ domestic political cycles. Therefore, a framework agreement is not the final consensus.

Huang pointed out that the US and China have shifted from mutual dependence and mutual profit in trade to pursuing their own interests. The long-term strategic competition from Beijing will continue to assert itself in the coming five years. The tensions have not been fundamentally resolved but merely shifted from short-term to long-term issues.

“Therefore, the current relaxation could quickly reverse in the next round of friction.”

Since joining the WTO, China has been viewed by the West as the biggest rule breaker. In April of this year, the Trump administration imposed high tariffs on China, highlighting that the trade issues with China go beyond tariffs, and China needs to fundamentally adjust its economic structure to rebalance its trade relationship with the US.

Yip Yaoyuan stated that China always says one thing and does another, a decades-old pattern, especially when it comes to unfavorable matters that China completely ignores. The current agreement mainly focuses on two aspects: lifting rare earth export controls and requiring the sale of TikTok. However, the key point remains China’s market openness and fair trade. China is likely to continue playing a waiting game, dragging its feet without fulfilling its promises.

He believes that under these circumstances, many things may not be resolved no matter how they are negotiated.

Yip Yaoyuan added that the current trade negotiations essentially have no concrete results. China promises more but fails to deliver, even if they propose some terms acceptable to the US, they ultimately do not uphold their end of the deal.

The structural confrontation between the US and China has made their mutual dependence a vulnerability. Trade between the US and China, once considered a cornerstone of stabilizing bilateral relations, has now become a bargaining chip for mutual sanctions.

Yip Yaoyuan observes that the US-China competition is not ordinary, but a struggle for great power hegemony and a zero-sum game. In this scenario, there is a lack of trust between the US and China. When both sides have this mindset, long-term, predictable cooperation between the two is becoming increasingly unlikely.

In the ongoing US-China trade war, China believes it has found the fatal weakness of the US and mimics Trump’s extreme pressure tactics, but all these methods have major flaws.

Beijing can pressure US companies through antitrust investigations, restrictions on Hollywood movies, and blacklisting some US exporters. However, if the pressure becomes too strong, foreign investment crucial for China’s employment and technological development will evaporate.

Additionally, China can use rare earths as a bargaining chip, but excessive pressure may encourage other countries to follow suit, subsidizing mining and processing and taking countermeasures.

Most importantly, Beijing has forgotten that it is an export-oriented economy. Excessive use of sanctions by China will backfire.

Huang mentioned that while rare earths can be an effective tool for retaliatory measures in the short term, continued overuse will incentivize the global transition of alternative supply chains. China will be labeled an unreliable supplier.

He stated that excessive pressure on the US will accelerate the shifting of foreign trade and supply chains, eliminating China’s status as the world’s sole supplier. This will lead to a decline in future profits in manufacturing and further outflow of capital and technology invested in China.

Recently, Chinese state media and officials have not hidden their promotion of so-called institutional advantages. The People’s Daily claimed that the Chinese Communist Party has “a blueprint that is painted to the end” and operates throughout the nation like chess pieces, contrasting it to the “myopic and flip-flopping” macro policies of some countries (such as the US).

Global Times published an editorial stating, “In today’s international situation, the frequent changes in policies of some big countries have cast a shadow of ‘unpredictability’ over world peace and development.”

Yip Yaoyuan pointed out that China’s so-called institutional advantage lies in its strong government control over the economy, opposing the capitalist market through a planned economy approach to develop its economy. He believes that this superiority in the system is merely a self-deception and irrational happiness. China possesses fundamental conditions for economic success: a large population, good education, and abundant resources which many other countries lack. However, without a fully open market, efficiency cannot be achieved; its lack of democratic supervision has led to severe corruption.

Yip Yaoyuan stated that China’s claimed institutional superiority is based on the assumption that the Chinese have never seen how China could become better under a more legal and free system. If China had transitioned directly to a democratic system in the wake of the Square Movement in 1989, it would undoubtedly be better off than it is now.

He remarked that democracy is not necessarily inefficient as claimed by the Chinese Communist Party. Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea are all democratic systems with high efficiency. Due to the lack of freedom in China, most of China’s top talents have departed. The truly talented and capable individuals are unlikely to stay in China.

In the US-China trade war, another propaganda strategy of China is the belief that the Chinese can endure hardship, while Americans cannot.

However, the Chinese middle class is becoming increasingly disillusioned, especially the younger generation who view hardship as futile. Many young people are either indulgent or passive, relying on their parents for support. The current societal conditions in China are vastly different from the 1980s and 90s when people still held hope for China’s improvement post-Cultural Revolution. Today, no one believes the Communist Party can reform itself, as seen in the wave of people quitting the Party, the Youth League, and the Young Pioneers.

Huang stated that the long-term narrative of the Chinese people’s resilience to hardship and the story that they can eat grass for three years, used to counter persistent conflict and capital unafraid of death, overlooks the expectations of the middle and working class on the economy as well as their personal interests.

Yip Yaoyuan mentioned that the legitimacy of the Chinese regime is somewhat based on public confidence in China’s economic growth. If the whole economy collapses and people cannot afford basic necessities, it will to some extent lead to a revolutionary sentiment.

He emphasized that revolutions are often unpredictable according to political science research, but this does not mean that significant economic failures will not create threats to the Communist Party from the public or even from officials within the Party who fear that the current system may lead to mutual destruction. The sheer size of the Communist Party organization means that not everyone believes Xi’s path is correct.

Huang added that to effect political change in Beijing, strong intervention by Western countries or foreign entities can be effective, citing examples from Cambodia and Myanmar where external interference prompted decisive actions from the local authorities.

This article covers the recent outcomes and the ongoing challenges in the US-China trade negotiations, shedding light on the complex dynamics between the two economic powerhouses and the implications for the global economy.