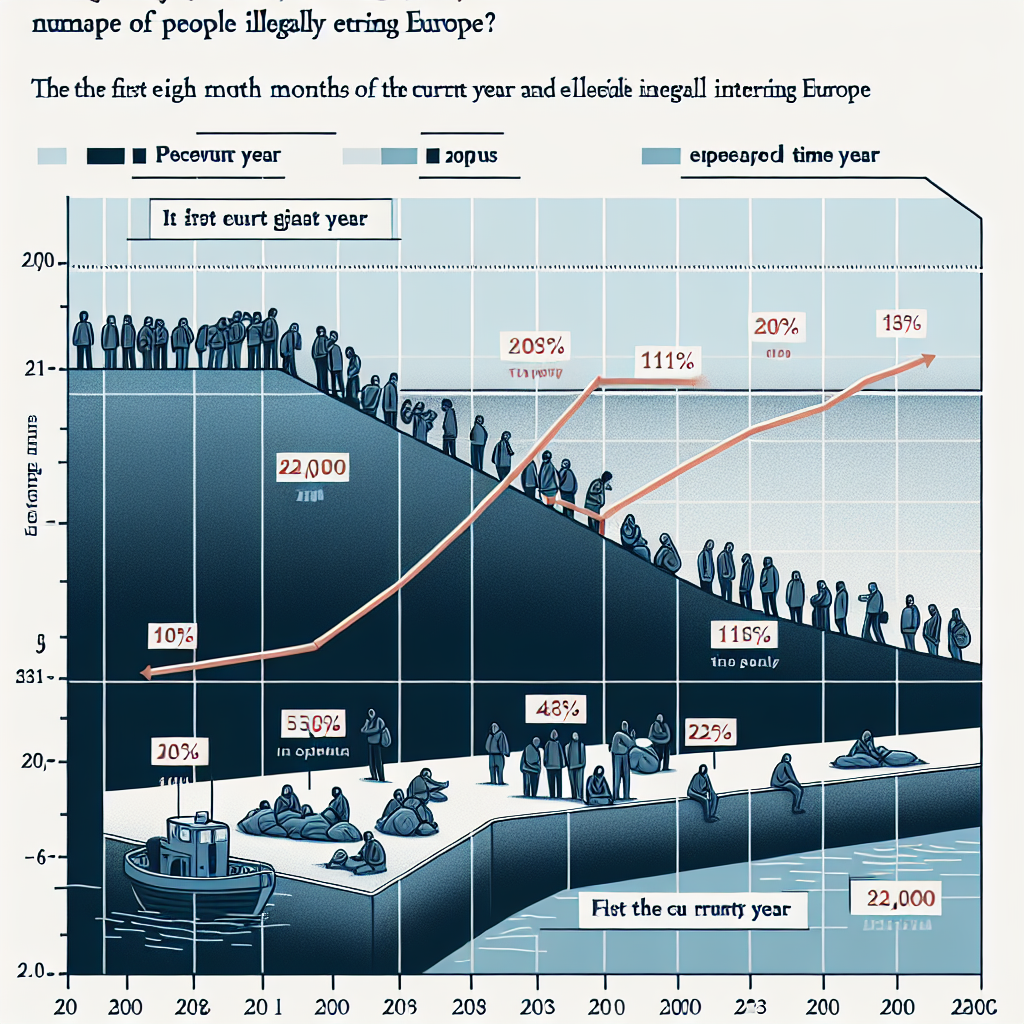

According to the latest data released by the European Union, 112,000 people illegally entered Europe in the first eight months of this year, a 21% decrease compared to the same period last year. Compared to the same period in 2023, the decrease is as high as 52%, when 231,000 people entered Europe through sea routes or border crossings. The decrease in new illegal immigrants is mainly due to the EU’s efforts to implement stricter policies to intercept illegal immigration.

In recent years, the majority of illegal immigrants entering the EU have mainly used three key routes. The first is known as the Central Mediterranean route, which mainly departs from Tunisia and Libya in North Africa, heading to Italy and Malta. The second is the Eastern Mediterranean route, mainly through sea routes from Turkey to Cyprus and Greece, including overland crossings through Greece and Bulgaria. The third is the West African route, where ships sail from countries like Mauritania and Morocco into the Atlantic Ocean, heading to the Spanish territories in the Canary Islands.

The illegal immigration crisis in Europe began in the mid-2010s, triggered by conflicts such as the Syrian civil war, leading to the largest wave of illegal immigration in Europe since World War II. In 2015, over a million people arrived in EU countries. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of illegal immigrants decreased, but from 2020 to 2023, it rapidly increased each year, reaching 380,000 people in 2023.

The main strategy adopted by the EU and its member states is to sign agreements with countries the immigrants pass through, enabling the interception and repatriation of illegal immigrants before they set foot on European soil and file for asylum.

As part of the agreement, the transit countries receive substantial aid and investment. Egypt has been promised 7.4 billion euros (8.1 billion US dollars); Tunisia receives 1 billion euros. The EU or its member states also provide training and funding for the coast guards, border officials, and police forces of these countries.

With such agreements gradually expanding to North and West African regions, their effectiveness is increasingly evident. In 2024, the year after the EU signed an agreement with Tunisia, crossings on the Central Mediterranean route dropped by 58%. Last year, an agreement between the EU and Mauritania reduced immigrant flow on the West African route by 52%.

The EU Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) now uses drones to patrol and monitor the airspace over Libya and Tunisia, immediately alerting local authorities upon detecting ships.

According to data from the non-profit investigative news organization Lighthouse Reports, Frontex has provided over 2,000 pieces of information on the locations of migrant boats to Libyan authorities in the three years leading up to 2024.

As the EU continues to sign agreements with more countries, violent abuses against illegal immigrants are increasingly being pushed further away from the European coast. The Tunisian government has been accused of abandoning thousands of detained migrants in desert areas bordering Algeria, while Mauritania has been accused of pushing illegal immigrants into Mali and Senegal.

In some cases, the Libyan coast guard hired by the EU is essentially a militia organization. Human rights groups have pointed out that some illegal immigrants detained or repatriated to Libya have suffered abuse, rape, or slavery. Malta has been accused of assisting deadly Libyan militias in driving boats out of its territorial waters.

Human rights organizations accuse the EU’s plan of being too harsh, relying on authoritarian regimes using violent means to deter illegal immigration, weakening oversight of abuses, and even obstructing rescue operations.

In August, the Libyan coast guard fired at a search and rescue vessel belonging to an organization while it was searching for a distressed boat.

The International Organization for Migration of the United Nations has reported that at least 456 migrants have died in shipwrecks in the Central Mediterranean this year, with over 420 individuals reported missing. Due to the closure of shorter routes like Western Sahara to the Canary Islands, many migrants are forced to take longer and more dangerous routes through Senegal or Gambia.

As the EU heavily relies on cooperation from foreign governments to block illegal immigration, it may find itself in a vulnerable position. Turkey and Morocco have begun to leverage their control over migrant flows to pressure the EU, demanding more funding or easing criticism of their foreign policies.

To address this, many European countries are taking more measures to prevent illegal immigration. Italy once tried to outsource asylum application processing to Albania, but the plan was rejected by the EU’s highest court. Greece has threatened to incarcerate rejected asylum seekers who refuse to leave.

Some argue that Europe should focus more on addressing the root causes of migration, such as eliminating poverty or conflicts. However, the willingness of Western countries to support nation-building or peacekeeping operations in countries like Afghanistan and Libya has significantly diminished after failed interventions.

(Adapted from The Economist)