Entering Manhattan’s Chinatown, the bustling streets are as lively as ever. Amidst the hustle and bustle, there stands a building with a profound sense of history, quietly witnessing the rise and fall of this community – the 116-year-old New York Chinese School. Since its establishment in 1909, this school has always carried the hopes of the community and the inheritance of culture. Regardless of the changing times, it has always been able to find a new position in the challenges it faces, completing one perfect transformation after another.

Principal Wang expressed to Epoch Times, “The mission of the New York Chinese School is to serve the children of the community, operate sustainably, and integrate with the mainstream, striving to pass on the Chinese language and culture.” Her words are not just a promise, but also a belief.

According to historical records, the New York Chinese School was born in 1909, during a time when Chinese people in America faced difficulties and discrimination. At that time, a special envoy from the Qing Dynasty’s Education Ministry, Liang Qinggui, went to the United States and proposed the idea of establishing schools overseas to continue Chinese culture. This idea received support from Chen Huanzhang, the chairman of the New York Chinese Public Association at that time. Chen Huanzhang keenly realized that only through education could the next generation of overseas Chinese establish themselves in America while not forgetting their roots.

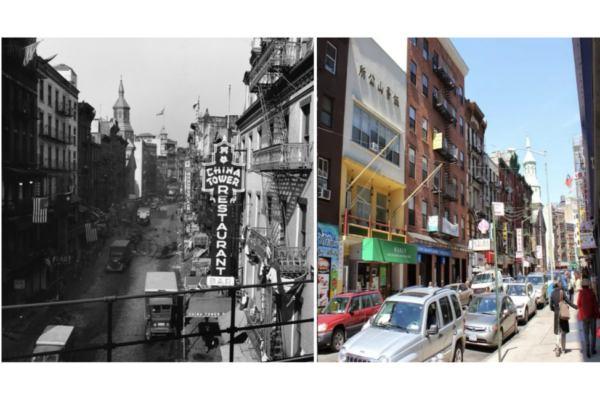

Thus, the Chinese School was born in a Catholic church on Mott Street. At the beginning of its founding, the school had only twenty students, but this small classroom ignited the hopes of the entire Chinese community. Over the years, the number of students increased annually, and the school moved multiple times until it purchased Public School 108 on 64 Mott Street in 1929 as its permanent location, providing the Chinese school with a relatively stable “home.”

For early Chinese immigrants, the Chinese School was not just a place for children to learn Chinese; it was also a spiritual stronghold for the community. Here, compatriots placed their longing for their homeland and found a strength to “preserve tradition even in a foreign land.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, a large number of new immigrants flooded into New York, and Chinatown experienced a peak in development. During this period, the Chinese School also entered its most glorious golden age, with over a thousand students enrolled and weekend courses attracting as many as two thousand students. The hallways of the school resounded with Chinese recitations, lion dance drumming, creating an atmosphere resembling a “miniature Chinese cultural city.”

During that era, there were few Chinese language schools, and many families traveled long distances from Brooklyn, Queens, and even New Jersey and Long Island for classes. For Chinese parents, providing their children with Chinese language and cultural education was a guarantee of their “roots.”

As a result, the Chinese School became the “second home” for many immigrant families. Many graduates went on to become doctors, lawyers, teachers, and elite professionals in various fields. Some returned to the community to serve as principals or teachers, carrying on the cultural heritage. The achievements of these alumni are not only a source of pride for the school but also a testimony to the profound impact of the school’s education.

In March 1943, during the most difficult period of World War II, Madame Soong Mei-ling visited the Chinese School in New York’s Chinatown as part of her diplomatic visit to the United States. The school was located at the heart of Chinatown at that time, serving as a cultural landmark in the hearts of overseas Chinese.

On that day, a banner reading “All overseas Chinese welcome Madame Chiang’s Assembly” was hung in front of the school building, with the bright blue sky and white sun flag waving on the street. Police maintained order, reporters and crowds gathered, and the scene was lively.

Madame Soong Mei-ling entered the school building, greeted teachers and students warmly, praised the Chinese School for holding steadfast in providing education in difficult circumstances, and nurturing the cultural heritage of overseas Chinese children. This historical moment became a highlight in the development history of the Chinese School and deeply engraved in the collective memory of the entire Chinese community.

In addition to language teaching, the Chinese School early on recognized that “culture is the best bridge.” Therefore, in its curriculum, it not only focused on traditional Chinese characters and literary classics but also offered courses in calligraphy, traditional painting, dance, music, lion dance, and Chinese opera. These contents allowed children to immerse themselves in the vast and profound Chinese culture while learning the language.

More importantly, these courses gradually attracted non-Chinese students to participate. The Chinese New Year lion dance, Mid-Autumn Festival calligraphy competitions, Confucius ceremonies…through the school’s activities, Chinese culture expanded beyond the Chinese community and reached a broader American society.

The school’s percussion band participated in national cultural celebrations, winning numerous awards, allowing more people to experience the Eastern rhythms and aesthetics firsthand.

Principal Wang Xianyun stated, “We hope that students not only learn the language but also understand the culture behind the language and bring this tradition to the world stage.”

Against the backdrop of America’s diverse culture, the Chinese School is no longer just a “Chinese language tutoring class” but an important bridge for cultural exchange between China and the United States.

However, as we entered the 21st century, the Chinese School faced new challenges. With New York City public schools increasingly offering Chinese-English bilingual programs, coupled with the rise of tutoring centers in the community, student sources gradually became dispersed. Additionally, the impact of the pandemic, increased economic pressures on families, changes in social and behavioral patterns, regular schools providing Chinese courses, population migration from Chinatown, among other related factors, led to a drastic drop in the number of Chinese School students to just over four hundred, a far cry from its golden age.

Faced with adversity, the Chinese School chose to transform once again. The school actively expanded online courses to break through geographical limitations and attract a wider student community; while strengthening connections with alumni and the community, raising resources, and continuing to fulfill the responsibility of serving the children of the community, striving to pass on the Chinese language and culture.

What is even more commendable is that, regardless of external changes, the Chinese School has always adhered to the belief that the “cultural spark cannot be extinguished.” The Sixty Association and former directors, alumni generously donated, former chairmen Wu Ruixian and Zeng Weikang (now a consultant to the Chinese Public Association), even donating all their salaries, establishing graduation encouragement funds with their forty-year intimate friend Wonton Company founder, subsidizing tuition fees, continuously supporting Chinese school students.

This “from the community, for the community” entrepreneurial spirit is what enables the Chinese School to operate sustainably, continuing the core values of a hundred years.

Today, the New York Chinese School is located in the Chinatown Building at 62 Mott Street. This five-story building houses 22 classrooms, a dance studio, a piano room, an indoor sports field, and a grand hall that can accommodate 450 people, making it one of the largest Chinese schools on the East Coast.

It is not just a school but a vivid chapter in the “history of Chinese immigrants.” From its humble beginnings with twenty students in 1909 to the golden age with thousands of students; from self-financing by compatriots to being officially recognized by the New York State Department of Education in 1967 as the accredited Absolute Charter School educational institution; from traditional classrooms to modern online classes… at every stage, the Chinese School has kept pace with the times.

Here, children learn the language, understand the culture, and shape their values; here, the community gathers strength, safeguards tradition, and builds a future together.

Over 116 years, the New York Chinese School, through its perfect transformations time and again, has exemplified what it means to be “a hundred-year-old school, forever youthful.” It will continue to safeguard this cultural spark, allowing Chinese culture to take root and flourish on American soil, blossoming even more brilliantly.