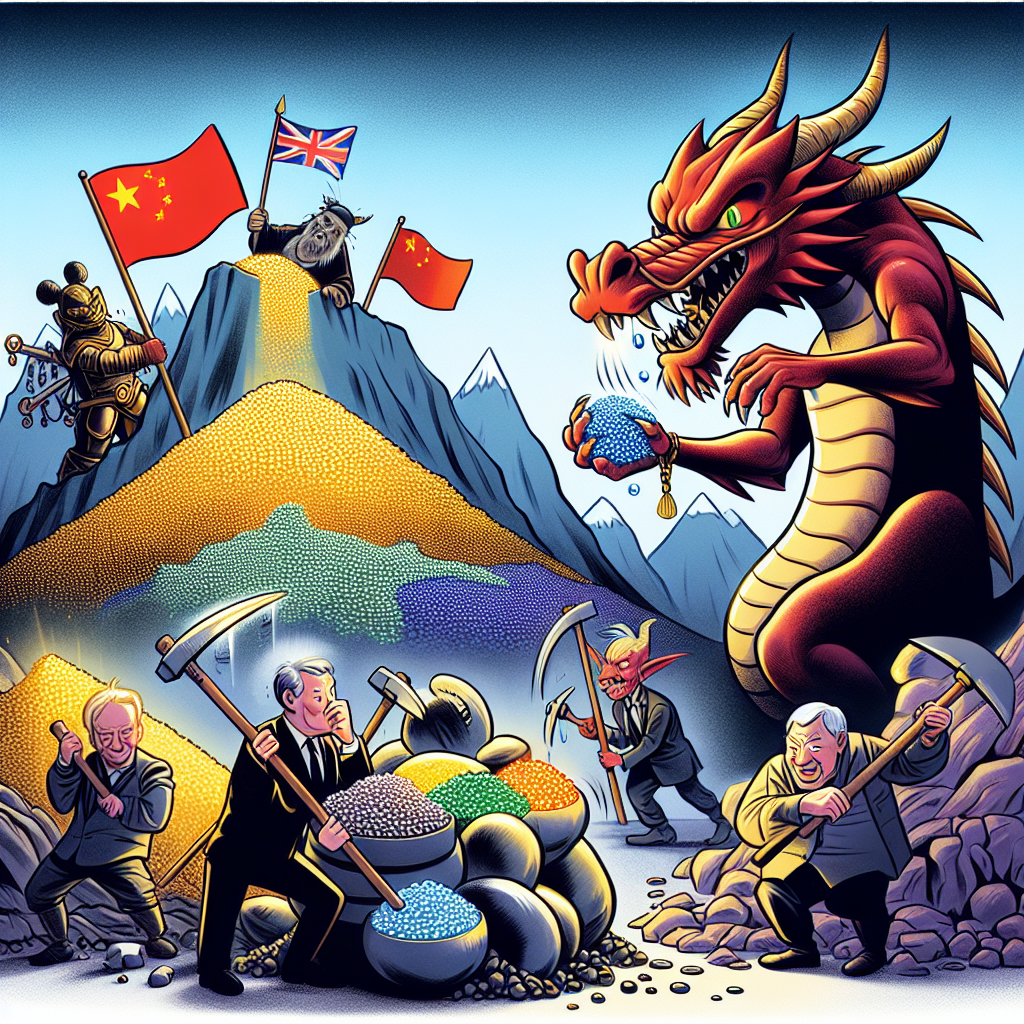

Beijing is using rare earth elements as an economic leverage, but Western countries are actively working to reduce their dependence on China and produce their own rare earth elements. The more the Chinese Communist Party tries to monopolize the market, the more other countries are seeking ways to break free.

Since April this year, China has implemented export controls on rare earth elements, putting global manufacturers in an emergency state. Ford once had to halt production at its Chicago plant for a week due to a shortage of rare earth elements.

Although Beijing later agreed to resume the export of rare earth minerals and magnets to the United States, concerns about supply chain disruptions persist.

Currently, Western countries have realized the serious threat of China’s resource monopoly and are beginning to try to break free from reliance on Beijing.

According to The Economist, experts from the Washington think tank, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), state that the United States is making efforts across the government to reduce its reliance on Chinese rare earth elements.

The Mountain Pass mine in California has been in operation since 2018, producing 47,000 tons of light rare earth oxide last year, with a goal to increase production to 60,000 tons by 2030. The U.S. Department of Defense has pledged to guarantee a minimum price for its production, higher than the levels before China restricted exports.

In Australia, Lynas operates the Mount Weld rare earth mine in Western Australia. With the support of the U.S. and Japanese governments, Lynas began producing heavy rare earth elements in Malaysia in May, becoming the first commercial entity outside of China to do so.

Lynas announced that its new plant in Malaysia has started producing dysprosium oxide, marking the first time the company has provided a product to customers that did not come from China. In June, Lynas is set to begin producing another rare earth element, terbium. Dysprosium and terbium are two highly sought-after rare earth elements.

In order to weaken China’s dominant position in the rare earth market, the United States has also agreed to sign a $258 million contract with Lynas to build a new processing plant in Texas.

The Australian government has also decided to provide a loan of $1.65 billion to Iluka Resources to construct a rare earth refining plant, hoping to break the long-standing Chinese monopoly.

Iluka has been mining zircon and titanium dioxide for paint manufacture for decades. The by-products of these minerals happen to include dysprosium and terbium.

Although it will take two more years to construct and launch the refining plant, Dan McGrath, the executive of Iluka Resources, pointed out that “this refining plant, along with Iluka’s investment in the rare earth industry, provides another option outside of China.”

The European Union has announced its support for rare earth projects in Malawi and South Africa in Africa, with hundreds of other projects planned globally; however, most of these plans are expected to launch in several years, according to The Economist.

Currently, there are 17 metals known as “rare earth elements,” with most of them not actually rare but rather widely spread around the world, just in limited mineable quantities.

They are called “rare metals” because they are difficult to separate individually, requiring over a hundred processing stages and a large amount of strong acid treatment, making the process complex. Additionally, some rare earth ores contain radioactive elements, improper treatment of which could lead to radiation pollution.

In the 1990s, Europe, particularly France, had a significant rare earth industry footprint. Today, over half of the world’s rare earth extraction and nearly 90% of refining operations are concentrated in China.