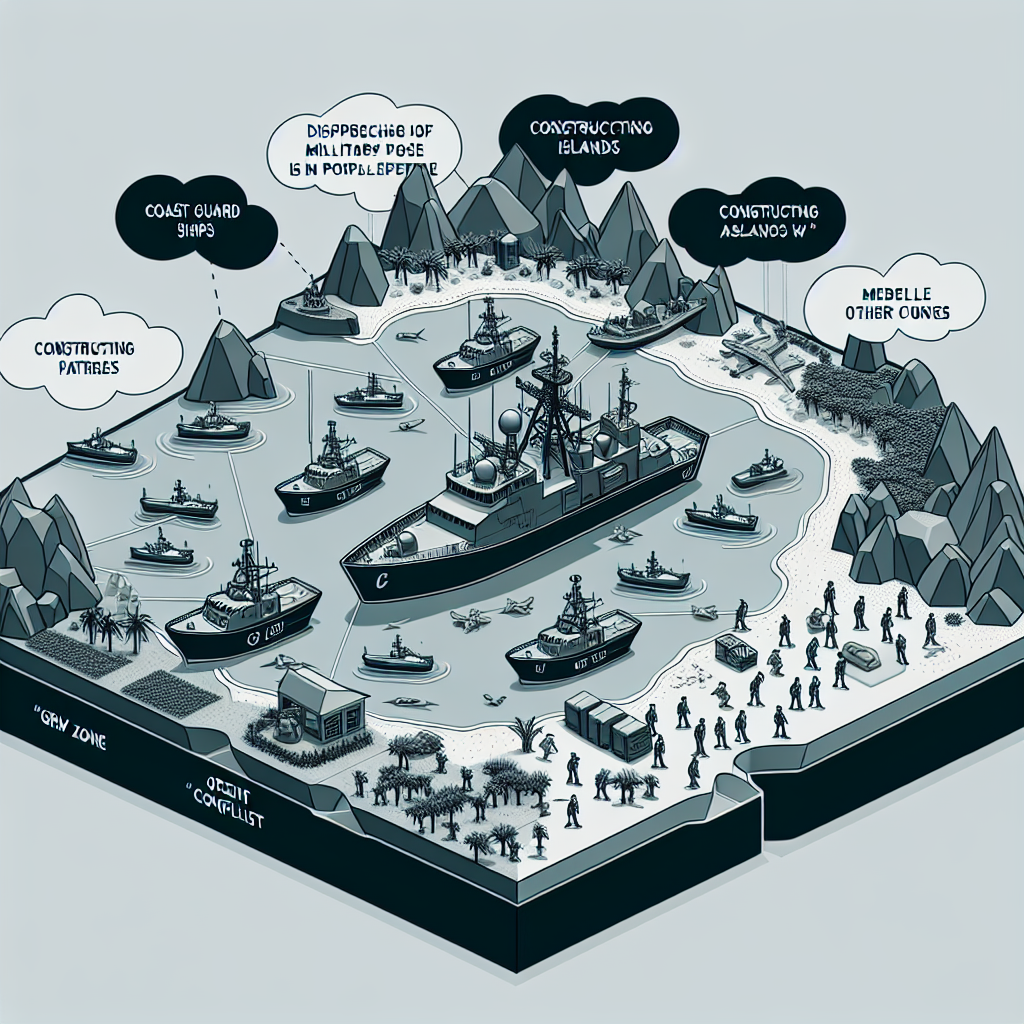

In the past decade, the Chinese Communist regime has been using the “gray zone” strategy in the South China Sea region, which does not cross the threshold of war. This strategy includes “non-military” provocations by coast guard ships, military patrols, island building, and interference with other countries’ oil and gas exploration, in an attempt to intimidate and threaten neighboring countries and alter the regional status quo. However, since 2021, Beijing’s actions in the South China Sea have been constantly frustrated, and this “gray zone” strategy is no longer effective.

In 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague ruled under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) that Beijing’s “nine-dash line” claim in the South China Sea has no legal basis and found China’s activities within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone to be in violation of international law.

China has refused to accept the ruling and continues to strengthen its military and coast guard presence in the South China Sea, conducting control and intimidation operations, especially targeting disputed areas like Ren’ai Shoal and Huangyan Island.

However, these threats and intimidations have recently proven ineffective.

Admiral Steve Koehler, the commander of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Fleet, noted in a speech at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington on June 17, that “China’s pressure did not work. It did not force Southeast Asian claimants to acquiesce or give up their sovereign rights.”

Koehler cited Beijing’s harassment and violent behavior towards Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, and particularly the Philippines over the past year, but in each instance, Southeast Asian countries refused to back down.

According to the U.S. military journal “War on the Rocks,” at the end of 2012, China took action to quickly occupy the long-held Philippines-controlled Scarborough Shoal. In 2013, then Chinese leader emphasized the goal of becoming a maritime power. These two events were seen as a turning point in Beijing’s South China Sea strategy: the Chinese regime became more aggressive in seeking control of the region.

However, China’s control in the South China Sea has not progressed, with setbacks in some areas. Now, Southeast Asian countries are willing to take risks in confronting China in strategically important or economically valuable locations. They have found that in the face of Beijing’s pressure in the gray zone, they can indeed hold their ground.

China’s gray zone strategy has faced repeated setbacks, but so far Beijing is unwilling to escalate to the use of lethal force. Chinese commanders have been instructed to avoid using military force but are increasingly employing dangerous “non-lethal” tactics against Southeast Asian countries, such as ramming, high-pressure water cannons, blinding lasers, and sound wave devices. If these tactics fail, China may temporarily de-escalate the situation in one area, only to restart the same pattern elsewhere shortly after.

Oil and gas exploration is a key example of how Southeast Asian countries have pushed back against Chinese pressure in recent years.

In the second half of 2021, Indonesia conducted exploration in the Tuna oil and gas area in the southern part of the South China Sea, prompting China to dispatch coast guard vessels to disrupt Indonesia’s activities. Jakarta responded by sending coast guard and naval ships to protect the exploration operation. After a standoff lasting three months, Indonesia completed drilling as planned.

In October 2024, Indonesia initiated a new round of drilling in a nearby area, with China deploying coast guard vessels while Indonesia dispatched an escort fleet. The drilling was completed on schedule.

In 2021, Vietnam also increased its resistance, approving drilling in the Nam Con Son field near Vanguard Bank, which supplies a significant amount of electricity to Ho Chi Minh City. Chinese coast guard ships harassed the area, and Vietnam sent naval vessels to escort, allowing the operation to proceed as planned.

Chinese coast guard vessels now patrol Vanguard Bank almost daily, monitoring ongoing extraction activities in Nam Con Son and Tuna oil and gas zones. However, China has gained nothing from these efforts.

Malaysia has the largest and most profitable offshore oil and gas industry in the South China Sea. Since late 2013, Chinese coast guard vessels have been continually harassing operations near Luconia Shoals.

While China successfully disrupted Malaysia’s drilling on the continental shelf in 2020, Malaysia’s state-run oil company, Petronas, has been actively expanding in the Kasawari Gas Field. Despite China’s daily patrols and diplomatic pressure through letters, Malaysia resisted and drilled a record 25 offshore wells in 2023 and another 15 in 2024.

The Philippines had accommodated Chinese requests for many years, but since President Marcos took office in July 2022, the country has taken a firmer stance, strengthening naval and coast guard patrols in disputed waters, and responding openly to harassment incidents.

This shift in posture has led to more frequent clashes, interceptions, water cannon usage, and laser-based confrontations between China and the Philippines. Yet, the Philippines has not backed down.

From February 2023 to August 2024, Chinese coast guard and militia attempted to blockade Second Thomas Shoal. The Philippine landing ship, BRP Sierra Madre, was stationed there and deemed in need of repairs. When the Philippines began transporting materials for repair, China used the situation as a pretext to block the area. By December 2023, the number of Chinese vessels in the vicinity increased to around 50, and the tactics became more aggressive.

This escalated into monthly physical clashes at Second Thomas Shoal, sometimes involving several Chinese vessels coordinating against Philippine military and civilian ships. The Chinese coast guard used high-pressure water cannons from multiple directions, causing windows to break, crew members to be injured (including a senior officer), and engines to be damaged. China also employed lasers and sound wave devices, temporarily blinding and disorienting the Philippine crew. However, the Philippines successfully completed their resupply missions each month.

In June 2024, this gray zone tactic reached a new height. The Philippine Navy used rigid-hulled inflatable boats to circumvent China’s blockade and resupply the Sierra Madre. Chinese coast guard vessels deployed inflatable boats to ram Philippine ships, even resorting to threats with knives and other weapons, resulting in a Philippine sailor having their fingers severed between the two vessels.

After this incident, China realized that its “non-lethal” gray zone strategy had reached its limit. If it triggered the U.S.-Philippine Mutual Defense Treaty, the United States would intervene in the conflict, leading to uncontrollable consequences. Subsequently, China and the Philippines reached a temporary agreement, easing tensions at Second Thomas Shoal. The Philippines completed its repair mission, achieving its goal, while Beijing gained nothing.

China’s actions at Second Thomas Shoal instead accelerated the reorganization of the U.S.-Philippine alliance. This standoff also led to a more active involvement of the Philippines in regional security structures. In July 2023, Manila and Tokyo signed the Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) to conduct joint military training and exercises. Subsequently, the Philippines also completed similar agreements with New Zealand and Canada in early 2025, with an agreement with France pending.

Currently, a new trilateral security alliance (U.S.-Japan-Philippines) has formed, and the U.S., Australia, Japan, and the Philippines have formed an Indo-Pacific Four-Corner Security Alliance Squad. Diplomatically, Manila, through its own experiences of Chinese coercion, successfully convinced 28 countries, including the United States, to publicly call on Beijing to adhere to the 2016 Hague arbitration ruling and abandon its unlawful maritime claims.

Furthermore, starting on August 4, India and the Philippines held joint naval exercises in the South China Sea for the first time, causing consternation in China. Unlike previous maritime activities such as joint navigation, transit exercises, and maritime partnership exercises, this Indian and Philippine naval cooperation activity aimed to enhance interoperability between the forces and demonstrate support for the Philippines during conflicts with China.