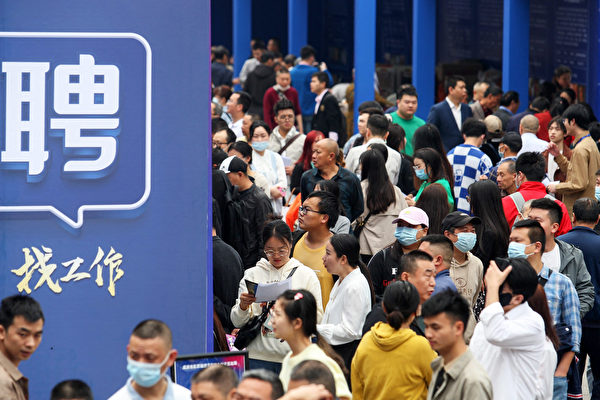

In recent years, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has frequently emphasized the concept of “employment stability” since General Secretary Xi Jinping’s first term, but the expanding army of unemployed nationwide has demonstrated the unstable nature of employment in China. Prolonged unemployment, intense competition, and enormous survival pressure have led to millions of unemployed individuals experiencing anxiety, low self-esteem, depression, and other psychological issues. A recent independent documentary titled “Graduation, Unemployment” truthfully captured these challenges. The film was quickly banned online, becoming a stark testament to the severe employment situation in China.

The concept of “employment stability” began to be frequently mentioned after the global financial crisis in 2008, and under Xi Jinping’s leadership, particularly as China’s economy faced challenges of transformation and structural adjustment, its strategic importance significantly increased. On July 31, 2018, the CCP Central Politburo meeting officially designated “employment stability” as the top priority among the “six stabilizations.” Since then, “employment stability” has become a fixed and crucial policy objective in CCP high-level meetings and government work reports.

However, the frequent enhancement of policies has only served to highlight the complexity of the problem. On July 9th this year, the State Council of the CCP announced 19 additional measures to stabilize employment, covering areas such as expanding enterprise employment loans, subsidizing companies to create new positions, and intensifying the implementation of “work-for-relief” programs, among seven other aspects.

For example, authorities have expanded support for special loans for stabilizing and increasing employment, significantly raised the unemployment insurance return rate: the return rate for small and medium-sized enterprises has been raised to a maximum of 90% from not exceeding 60%, and for large enterprises, it has been raised to a maximum of 50% from not exceeding 30%. Furthermore, companies and organizations that employ registered unemployed youth aged 16 to 24 will receive a one-time expansion subsidy of up to 1,500 yuan per person.

The government has also expanded the large-scale “work-for-relief” program. Official media reported that the National Development and Reform Commission of the CCP recently allocated an additional 10 billion yuan to support 1,975 small and medium-sized infrastructure projects in 26 provinces and cities, claiming to help stabilize employment and increase income for 310,000 key individuals.

As of the end of June, the National Development and Reform Commission, along with the Ministry of Finance, had allocated a total of 29.5 billion yuan in central investment for the “work-for-relief” program in 2025, supporting nearly 6,000 projects and expecting to create jobs for over 700,000 disadvantaged individuals, with labor compensation exceeding 11 billion yuan.

Officially, these policies are said to help ease the burden on businesses. However, in the economic winter, whether these subsidies provide a drop in the bucket or a timely help for struggling businesses remains unknown.

Many analysts and market estimates suggest that the actual number of unemployed people in China could reach tens of millions. While these temporary measures may provide temporary relief, they are only a short-term respite rather than a long-term solution. The official urban unemployment rate maintains a relatively low level, but its statistical limitations (not including the vast hidden unemployment in rural areas) do not accurately reflect the severity of actual unemployment.

In recent years, the number of university graduates in China has continued to increase, from 11.58 million in 2023 to a record high of 11.87 million in 2024, with an estimated 12.22 million in 2025. The enormous supply versus limited demand has created a significant contradiction, earning 2025 the mocking title of the “most tragic university graduation season in history,” where graduation certificates have become the “first proof of unemployment” for many.

The recently banned documentary “Graduation, Unemployment” depicts the harsh realities faced by individuals like Ning Shan, a master’s graduate from a prestigious university, who finds herself a victim of the employment crisis. Ning Shan studied civil engineering during the peak of China’s real estate industry. However, by the time she graduated with her master’s degree in 2022, the real estate sector had plunged into a deep recession, leaving even established professionals jobless and newcomers like her with no ground to stand on.

“Why did I choose to study civil engineering in the first place? Have I gone mad?” she laments, as she found herself immediately facing challenges — becoming a typical example of “skill mismatch” as described by some economists. When the skills she acquired are no longer in demand, her efforts over seven years of education (including the master’s program) and the 300,000 yuan investment in her education seemed futile.

Confidently opening job search apps, she discovered that the depreciation of qualifications far surpassed her expectations: even basic positions such as registration officer and audit assistant required a master’s degree at a minimum, yet offered salaries ranging only from 4,000 to 6,000 yuan. Even without any expenses, it would take her six years just to barely cover the cost of her master’s education.

For ordinary undergraduates or college students, the choices are even more limited. Worn down by reality, many are forced to enter the electronic market to sell cell phones or shift careers to real estate or car sales. With millions of graduates joining the job market every year, there is a significant number compelled by life pressures to become delivery workers or run food deliveries.

In the face of desperation where she couldn’t secure a job and even affording meals became an issue, unemployed civil engineering master’s graduate Ning Shan resorted to live streaming. In a self-deprecating manner, she dubbed it as “earning instant noodle money through live streaming” — “just one day of live streaming could afford me noodles for that day.”

Lacking experience in live streaming and a disdain for what she considered as “selling herself,” her income remained meager over the following months. She cut down her expenses to the bare minimum: no social activities, no food deliveries, relying solely on online platform coupons for daily necessities. Even then, she could barely manage to sustain her basic living.

With millions of fresh graduates pouring into the job market each year, the degree of struggle and the story of individuals like Ning Shan, a master’s graduate resorting to “earning noodle money through live streaming”, reflect the depths of social challenges faced by this generation.

The employment challenges aren’t limited to recent graduates but also extend to many middle-aged career elites who find themselves plummeting from the heights of success into the abyss of difficulties and transitions.

Take Chen Tao, a philosophy master’s graduate from a top-tier university, for example. He had held senior writing positions for publications like “China Newsweek” and was enticed with a high-paying job as a senior journalist at “Southern Weekend,” later working as a senior writer for Luo Yonghao’s studio. Living in a luxurious environment in Beijing, he enjoyed a rewarding career. However, in his middle-age, he faced the harsh reality of unemployment and had to resort to delivering food. After 15 years in Beijing, he couldn’t even muster 100 yuan.

On March 26, 2023, after multiple failed job attempts, Chen Tao posted a self-narrated video on social media, confessing, “I give up, I’m a food delivery guy, a philosophy master’s graduate from Sichuan University, a former senior journalist at ‘Southern Weekend’… unemployed for over half a year…” This video quickly went viral on Weibo, with “38-year-old philosophy master’s graduate delivering food” becoming a hot topic, drawing countless netizens’ attention and empathy.

In the course of over a year of unemployment, Chen Tao tried various jobs, including filming wildlife conservation videos in Tibet as a director, setting up a fruit stall in Chengdu, and even selling fruits while lecturing on the “Tao Te Ching,” albeit for just half a month. Additionally, he consistently shared philosophy knowledge and professional insights on social platforms.

At the beginning of 2024, after caring for his sick mother, he applied for a journalism teacher position at a private university in Xi’an and joined successfully. Looking back at his tumultuous journey over the past year, he admitted to earning less than a hundred thousand yuan in total, most of which was spent, with barely any savings.

The story of Xiaoqiang in the documentary “Graduation, Unemployment” depicts the structural contradictions in Chinese employment. Xiaoqiang graduated from a vocational nursing program at a school in Chongqing. He had believed that the aging population would bring significant job opportunities in the elderly care field, yet he couldn’t find joy in the reality he faced at his graduation ceremony in 2023.

“What can we do with our major?” he complained about the low industry salaries (internships paying only 1,500 to 2,000 yuan, with regular salaries capping at just over 3,000 yuan), alongside the expectation of being on call for 24 hours and working night shifts. Coming from a less affluent background, he eventually had to reluctantly put on a delivery vest and become a food delivery worker.

Reports from organizations like Zhaopin Recruitment confirm this helplessness: in recent years, university employment rates have been decreasing, with many graduates forced to reduce their salary expectations. Many signed employees received lower monthly wages than expected and had to resort to so-called “flexible employment” options like delivery, ride-hailing services, and live streaming, showcasing the escalating structural unemployment and employment pressure in China.

In the mountainous region of Ningxia, the experiences of college graduate Ma Cunjun reveal an even deeper sense of powerlessness at the grassroots level. After graduating from high school, he hoped to leave his hometown but due to a lack of background and education, he could only enter the lowest threshold factory assembly line. After just a few months, he was told upon returning home for the Chinese New Year that they “didn’t need him anymore.” From then on, his life consisted of scrolling through his phone to find daily gig work and tending to corn fields.

At the age of 20, he tried moving to the city, spending all his money in vain attempts, eventually seeking refuge with his elder brother Ma Youhu, who had a higher level of education. However, facing repeated rejections in job hunting himself, Ma Youhu, as a college graduate, was also turned down after a brief interview. He remarked, “It’s hard for those with bachelor’s degrees to find jobs, let alone someone like me with only a college degree. I have to accept reality.”

For individuals like Ma Youhu, who possess specialized skills but continually struggle to secure jobs, do the temporary, low-paid jobs provided by the government’s “work-for-relief” programs truly offer a long-term solution for their livelihood and career development? While these policies may provide immediate relief for some, for tens of millions facing structural unemployment, it’s merely a temporary reprieve, not a sustainable solution.

In conclusion, the documentary “Graduation, Unemployment” aptly states: “This is a suffocating era, where fresh graduates are locked out of job opportunities before they even have a chance to knock on the employment door.” This statement precisely captures the difficulties faced by the current Chinese youth — trapped amid historical circumstances and bearing the brunt of structural unemployment. Their anxiety is not empty but born out of harsh realities, and their silence is not acquiescence but borne out of deep powerlessness.

The film points out that as “graduating into unemployment” shifts from a warning to a norm, and even highly-educated elites struggle with middle-age unemployment, every systemic issue in education, employment, and the economy is uniquely reflected in their experiences. With the CCP government continually stressing “employment stability” and intensifying policy measures, the enormous pressure for social stability and the escalating difficulties faced by the population become increasingly apparent. While these policies may offer short-term relief for some groups, without addressing the underlying economic structural issues, boosting confidence in the private sector, and revitalizing market dynamics, the battle for “employment stability” may continue to replay in the cold numbers and struggles of countless individuals, lacking a sustainable solution.

“What the unemployed truly need is a fair starting point, but this point seems insurmountably distant.”