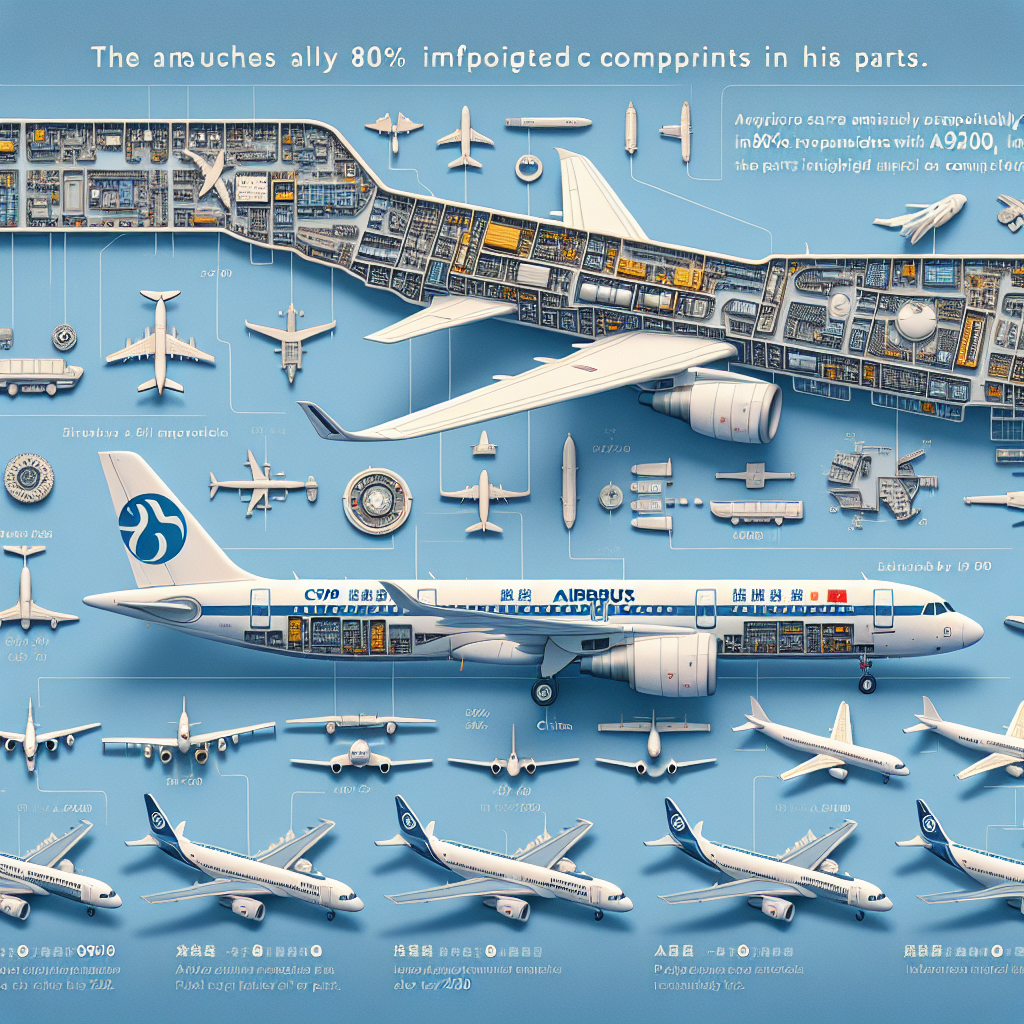

China’s C919 passenger aircraft not only relies on imported components for 80% of its parts but also shares many parameters with the Airbus A320. According to former Airbus executives and senior officials in the French intelligence community, a particular Airbus A320 purchased by China after 2000 has no flying or maintenance records, making it a “ghost plane.”

It is widely believed in the industry that this “missing” A320 was dismantled and used in the replication of the C919. China utilizes reverse engineering to replicate Western technology, extending beyond the aerospace industry to fields such as communication equipment, electric cars, and high-speed rail.

A recent report in the French economic magazine “Capital” revealed that in the early 2000s, China purchased two A320 aircraft, with one mysteriously disappearing without being registered for operation. It is speculated that this aircraft was dismantled for reverse engineering, leading to the creation of the “replicated aircraft” C919.

Public data indicates that the C919 and A320 have nearly identical fuselage lengths, heights, empty weights (excluding fuel and passenger weight), and maximum takeoff weights.

Patrick Devaux, former Vice President of Economics and Research at Airbus, expressed concerns about the missing A320, stating that overnight it became a “ghost plane” and implying that China might be replicating every component of the aircraft.

Furthermore, several other sources corroborate this report.

In January of this year, the former head of economic intelligence at the French Directorate General for External Security (DGSE), Alan Juillet, revealed in a documentary aired on French public broadcaster M6 that one of the two A320 aircraft sold to China in the early 21st century disappeared from radar without ever flying.

Reports from airliners.net in April 2007 and “Air & Cosmos” magazine also indicated the mysterious disappearance of an A320 aircraft delivered to China, with no records showing that it was handed over to a Chinese airline or that maintenance records were returned to Airbus.

At the Paris Air Show in June, Patrick Devaux told the English edition of The Epoch Times, “When the C919 appeared, we immediately thought, this is an A320,” emphasizing the unexpected nature of China potentially dismantling and replicating the aircraft.

According to “Capital,” Airbus has refrained from publicly condemning the issue due to concerns regarding potential commercial retaliation, particularly since Airbus has plans to establish a large A320 assembly plant in Tianjin, China, and had already sold over a hundred planes to China.

The report by M6 mentioned that Airbus continues to deny this fact. Devaux indicated, “China is a huge market, and we need to maintain good relations.”

The C919 and A320 are both single-aisle narrow-body aircraft, with the C919 slightly larger than the A320 but overall similar in size.

The C919 standard model has a length of about 38.9 meters, a wingspan of about 35.8 meters, and a height of about 11.95 meters. The A320neo standard model has a length of about 37.57 meters, a wingspan of about 34.1 meters, and a height of about 11.76 meters.

Additionally, they are comparable in terms of maximum takeoff weight, empty weight, and passenger capacity.

For the C919 standard model: maximum takeoff weight of 75.1 tons, empty weight of 45.7 tons, standard passenger capacity of 158-168 people, and an enhanced model that can accommodate up to 190 people.

For the A320neo standard model: maximum takeoff weight of 72.5 tons, empty weight of 42.6 tons, and passenger capacity ranging from 158 to 192 people.

The C919 aircraft is touted as a flagship product of Chinese high technology but still heavily relies on Western technology. According to reports from GIFAS (French Aerospace Industries Association), approximately 80% of the C919 components are sourced from American or European suppliers, including the LEAP engine developed jointly by the Safran Group from France and General Electric from the United States. This engine is primarily used in Airbus A320neo, Boeing 737 MAX, and the Chinese C919.

Director of the Institute for National Defense Strategy and Resources at the Taiwan Institute for National Defense and Security Studies, Su Ziyun, stated to The Epoch Times, “The Chinese Communist Party is adept at reverse engineering, but there are key technologies that cannot be copied. Copying the core of a chip or an engine is beyond their capabilities. Chinese netizens jokingly say that Communist China’s airplanes all have heart diseases, which is quite insightful.”

In April of this year, Florian Guillermet, Director of the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), told the French magazine “L’Usine Nouvelle” that China’s single-aisle aircraft manufacturer COMAC’s C919 will need to wait 3 to 6 years to obtain EASA certification, requiring verification tests on aircraft design and certain components along with test flights. Additionally, COMAC has not yet applied for certification with the United States Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

While developing aviation engines in China is a long-term endeavor, the Communist Party excels in stealing technology from large Western corporations. In 2022, a U.S. court sentenced Chinese intelligence officer Xu Yanjun to 20 years in prison for attempting to steal commercial secrets from General Electric Aviation and the Safran Group, both of which supply vital systems for the C919.

China’s replication of Western technology extends beyond the aviation industry. Telecom giants like Huawei and ZTE initially developed by copying Western patents but faced sanctions from the U.S. and EU for intellectual property infringements.

Automotive giants BYD, Chery, and Geely directly borrowed designs for their first-generation models from the West, particularly mimicking Tesla in the electric vehicle sector, implementing similar strategies in software and battery systems.

China’s J-20 fighter jet has long been compared to the U.S. F-22 Raptor, with noticeable similarities in stealth coatings and radar technology.

China’s high-speed rail industry initially obtained technology from companies like Kawasaki Heavy Industries from Japan, Alstom from France, and Bombardier from Canada through technology exchange, assembling and producing them domestically, eventually surpassing these companies’ products.

According to “Capital,” if the C919 obtains EASA certification, it will pose a challenge to the EU similar to Chinese electric vehicles, disrupting the Airbus dominance. Just as Chinese electric vehicles compete on price and are expanding market share in Europe, Chinese aircraft could potentially undermine Airbus’s stronghold.