On May 20, 2025, the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics issued a rare notification, naming Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and seven other provinces and cities, as well as three major state council departments including the Ministry of Science and Technology, for the issue of falsifying statistics. This has sparked heated discussions among the public.

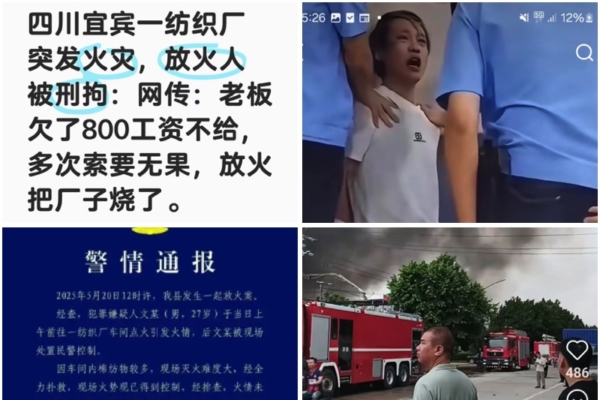

Simultaneously, a 27-year-old worker in Yibin, Sichuan set fire to his employer’s textile factory after failing to receive 800 yuan in unpaid wages, causing economic losses amounting to tens of millions. Similar incidents are not isolated cases. In December 2024, violent protests erupted in places like Jiaxing, Shandong, Guigang, and Chenzhou due to wage arrears, resulting in workers setting factories on fire or engaging in clashes with riot police.

These events collectively point to a deeper problem: the flaws in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) system, combined with economic pressures, have led to the rapid escalation of labor disputes and a crisis of trust in Chinese society, plunging it into a serious institutional dilemma.

The notification issued by the National Bureau of Statistics on May 20th directly accuses economically developed provinces like Jiangsu and Zhejiang, as well as state council departments of engaging in hidden falsification, statistical intervention, and falsification of enterprise data. Jiangsu, in particular, was prominently featured in this report. Previously, Jiangsu claimed that its GDP reached 13.7 trillion yuan in 2024, with a growth rate of 5.8%, sparking a debate on whether it was surpassing Guangdong.

Falsifying statistics in China is not a new phenomenon, from the era of Mao Zedong’s “high yields per unit area” to the post-reform era of “officials creating numbers, and numbers creating officials,” data falsification under the CCP system has always been a systemic “performance.” Former Premier Li Keqiang openly expressed his disbelief in the GDP numbers reported by various provinces, and he even created his own observational method known as the “Keqiang Index” to better understand China’s economic reality.

Unlike other forms of crackdown under the CCP, such as bribery, political cliques, or double-dealing, “statistical falsification” has never been a significant focus for cleaning up in the party. The high-profile disclosure of data falsification in this notification is considered unusual by outsiders, particularly because of its targeting of economically prominent coastal areas, leading to speculation about the political motivations behind this notification.

The Youtube channel “LT Vision” believes that the provinces in China have been ordered to falsify data, which cannot simply be attributed to local officials trying to advance their careers by fabricating achievements. Instead, it is seen as falsification personally directed and orchestrated by CCP leader Xi Jinping. Xi demands a 5% annual GDP growth rate, which needs to be distributed among various provinces, especially economic powerhouses like Jiangsu and Zhejiang, in order to fulfill the tasks assigned by the Party Central.

According to “LT,” while the CCP’s economic data falsification used to involve some “shame,” such as adjusting the base figures of the previous year, now Xi’s regime has escalated to a level where even with terrible structural data, the end result is presented as positive, ensuring that the GDP figures exceed 5%.

Such bold and blatant falsification aims to temporarily shield the Chinese people from acknowledging the country’s economic decline, maintaining belief in the miraculous growth narrative to sustain people’s trust in the CCP and secure its authoritarian stability. Once the public realizes that China is entering a period of low to moderate growth, coupled with an aging population and rising unemployment rates, doubts about the CCP’s absolute rule will arise, even within the party itself, challenging Xi’s leadership, which is his worst fear.

Chinese expert Wang He pointed out to Epoch Times that the audits and inspection reports of the CCP are essentially political tools, which require unified deployments by the Central Propaganda Department in terms of content publication, reporting strength, and whether it becomes a media focus. This nationwide coverage of data falsification suggests high-level directives, with these measures seemingly enhancing statistical governance on the surface but actually indicating a fundamental restructuring of the party’s power system, potentially signaling internal power struggles within the CCP.

Jiangsu and Zhejiang are crucial bases for the “Xi faction,” with Li Qiang previously serving as the Party Secretary of Jiangsu Province and Zhejiang Governor, and Xi himself having been the Party Secretary of Zhejiang.

Wang He questioned whether the central authorities selecting certain provinces as examples, particularly targeting the strongholds of the Xi faction like Jiangsu and Zhejiang, might indicate a challenge to Xi’s political standing, showing signs of his power being challenged.

The false economic growth covers up issues such as unemployment and weak consumption, misleading policy-making and exacerbating the societal trust crisis. The cost of beautifying local economic data is the concealment of the real struggles faced by lower-tier laborers. When the lies of fabricated data collide with the reality of despair, a massive fire becomes the only way to communicate.

On May 20, 2025, a 27-year-old worker in Jin Yu Textile Factory in Yibin, Sichuan, named Wen, set fire to the factory after failing to receive 800 yuan in wages, causing a fire that lasted 37 hours and led to millions in losses. This event reflects the desperation of grassroots laborers in seeking their rights. According to circulating information on the internet, Wen had attempted to claim his wages through legal means but was met with excuses from the factory. Faced with family poverty and ailing relatives, Wen resorted to extreme measures after his efforts to recover his wages failed.

Even though Wen has been detained and faces charges of arson, public opinion on social media has expressed more sympathy towards him, calling him “Brother 800.” Netizens commented, “800 yuan may be trivial to the boss but could be life-saving for a worker.”

Behind these violent wage-related incidents lies a severe lack of channels for labor rights protection. On one hand, enterprise unions often appointed by employers fail to represent workers’ interests, making it difficult for workers to assert their rights, thus escalating labor disputes. On the other hand, local governments often view wage claims as “malicious” acts, leading them to use force to suppress them, further intensifying the labor-management conflicts.

In December 2024, similar events erupted across multiple regions in China: workers at packaging factory JUMPAC in Pinghu, Jiaxing, Zhejiang set fire to the factory due to wage arrears deemed as “malicious claim for wages.” In Shandong, workers set fire to the QiDong HaiTong cold chain warehouse under construction by LANRun Group for withholding their wages. In Guangxi, hundreds of migrant workers in Zhongshan County, Hezhou, rioted over unpaid wages, confronting riot police with iron bars, resulting in some police officers being chased away. In Hunan, farmers in Guitang County, Chenzhou clashed with riot police over wage claims, with protesting citizens wielding iron bars attacking the police and causing them to flee.

These incidents indicate that wage arrears leading to violent protests have evolved from individual actions to collective conflicts, reflecting the intensification of labor disputes and the accumulation of societal resentment.

Scholar Tang Gang from Sichuan, speaking to Radio Free Asia, pointed out that under the pressure of economic downturn, social relations in Chinese society are shifting from a traditional society of “resolvable, inclusive, and coexisting conflicts” to a “harsh fight society with irreconcilable and intolerant struggles.” This marks over a decade of social transformation with one person claiming credit.

This “one person” mentioned by Tang Gang is believed to allude to CCP leader Xi Jinping. This thread can be traced as follows: Xi Jinping demands a 5% GDP growth rate – the collusion between local governments and companies to fabricate data – companies relieving financial pressures by withholding wages – workers bearing the brunt of the conflict, igniting the fuse of violent protests among the working class.

False data conceals economic realities, local authorities disregard labor rights for political achievements, leaving grassroots workers with no recourse, ultimately resorting to violence in expressing their desperation, leading China into a vicious cycle of institutional crisis. Despite the CCP’s current emphasis on “statistical rectification,” which targets data falsification, it increasingly appears as a tool for power games without addressing the root issues within the system.

The sympathy from netizens towards “Brother 800” and the approval of violence reflect society’s anger against injustice and disappointment with the system. This fire not only destroyed the factory but also ignited the profound crisis that urgently needs to be resolved in Chinese society.

As a Guangxi netizen named “Phantom” observed, “This fire has pierced the abscess of labor-management conflicts and revealed a heavy question… When 800 yuan becomes the final straw that crushes humanity, should we reflect on whether there is a ‘bridge of empathy’ missing between the boss’s ‘justified’ attitude and the worker’s ‘no way out’ dilemma?”

Wang He told Epoch Times that the fundamental contradiction between the political structure and economic mechanisms under the CCP’s authoritarian system has pushed Chinese society into a severe “institutional crisis.”

On one hand, the CCP’s governance logic centers around stability maintenance, prioritizing “social stability” over the rule of law, fairness, and justice, resulting in an imbalanced power system. In such a system, data falsification is not just a tool for promotions through “officials creating numbers, and numbers creating officials,” but also a political task from top to bottom, weakening the real feedback mechanism between the market and policies, leading to China’s economic decision-making drifting further away from reality.

On the other hand, the institutional channels that were supposed to alleviate societal conflicts, such as unions, courts, media, and People’s Congress representatives, have become mere decorations under the CCP’s authoritarian system, losing their function of balancing capital and protecting labor rights. Labor-management conflicts cannot be resolved through institutionalized channels, eventually erupting in violence and extremism.

Wang He pointed out that even more distressing is that when the state machinery faces social conflict, it always chooses to protect the interests of the privileged, even deploying police forces to suppress workers’ rights protection, eroding public confidence in “social justice” entirely. Chinese society is losing the most basic trust – not only in government data but also in the rule of law, fairness, and the prospects for the future collectively leading to a sense of despair.

Without systemic reconstruction and political power constraints, this institutional crisis in Chinese society will continue to deteriorate, possibly erupting into a larger-scale social crisis at a critical junction.