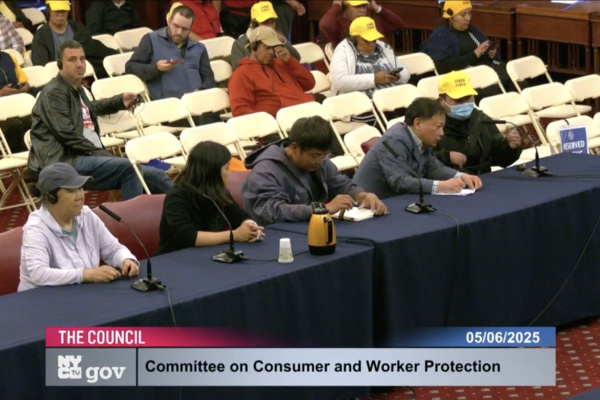

On Tuesday, May 6, the New York City Council’s Committee on Consumer Affairs and Worker Protection held a supervisory hearing to review and discuss the enforcement status and permit system for street vendors. Many Chinese vendors from Flushing attended the hearing to testify in support of reforms to the permit system.

Since 1979, the number of permits for non-food vendors has been capped at 853, and the Mobile Food Vendor (MFV) permits for food vendors have been frozen, causing over 10,000 people to wait in line. Many unlicensed vendors are forced to rent permits at high prices illegally, leading to a thriving underground market.

To address the bottleneck in issuing permits, the City Council passed Local Law 18 in 2021, requiring the city to issue 445 new food vending permits annually starting from 2022 for ten years and establishing the “Street Vendor Enforcement Office.” This unit was integrated into the Department of Health in 2023, but due to administrative inefficiencies and poor coordination, the permit issuance progress has severely lagged behind, sparking strong dissatisfaction among vendors and council members.

In addition to reviewing the implementation of Local Law 18, this hearing also discussed four vendor policy reform bills: Nos. 408, 431, 1164, and 1251. Proposal No. 408, introduced by public advocate Jumaane Williams, advocates for the establishment of a dedicated unit under the Small Business Services to provide vendors with education, training, and compliance guidance to “end the criminalization of street vendors as much as possible.”

Proposal No. 431, put forth by Council Member Pierina Sanchez, plans to gradually increase the number of mobile food and general vending permits from 2025 to 2029, ultimately eliminating the cap. The Independent Budget Office (IBO) estimates that this policy could generate up to $59 million in annual tax revenue for the city.

During the hearing, the Department of Sanitation (DSNY) responded to questions about confiscated property from unlicensed vendors, listing three main seizure situations: (1) unlicensed operating mobile food carts; (2) selling goods without a permit; (3) being deemed as “abandoned property,” such as when no one claims the items on-site or when enforcement officers find no one present.

The DSNY noted that vendors receive redemption notices after confiscation, with the first two days waiving storage fees and subsequent daily charges of $16. Failure to redeem within 90 days will result in automatic forfeiture, with items being donated, composted, or disposed of. Non-perishable food items are donated to food banks, while other goods are given to non-profit organizations. As of the end of April, only 16% of properties had been redeemed, with 46% being processed or discarded.

The IBO stated that even with the complete removal of the vendor permit cap, the vendor numbers are unlikely to experience explosive growth, as engaging in vending is closely tied to individual socioeconomic conditions rather than just policy changes. If 10% of the waitlist (approximately 2,000 people) were issued permits, the city could see an increase in tax revenue of $5.9 million annually. If all permits were issued, tax revenue could reach $59 million.

The average annual profits for vendors are approximately $35,000 for general merchandise vendors and $46,000 for food vendors. Legalization can help avoid steep fines and property confiscation, significantly impacting individuals. However, there are still barriers to legalization, such as clearing past fines and adhering to current regulations on spacing and hygiene requirements.

Representatives from various Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) and supermarkets expressed opposition, with Evan Sweet, Community Operations Director of the Meatpacking Business Improvement District, pointing out that vendors block fire hydrants and store entrances, highlighting the inadequate current enforcement and urging comprehensive planning to address the lack of enforcement capabilities. He emphasized that simply expanding permit numbers would further complicate the situation for street vendors and lead to worse outcomes in New York City.

Barbara Blair, President of the Midtown Fashion District Alliance, stated that the current ticketing system is ineffective, and vendors disregard fines, with the number of summonses being so high they could “cover the entire living room wall as wallpaper.” She criticized the city for overly focusing on permit quantity while neglecting actual enforcement and the chaos in public spaces, advocating for regulations that only allow vendors to operate at the edge of sidewalks. She stressed that spatial planning and enforcement should be prioritized in legislation.

Nelson Eusebio, Government Relations Director for the National Supermarket Association, argued that New York City’s current unrestricted vending system has severe flaws, leading to overcrowded sidewalks, unregulated vendors, and inconsistent enforcement, creating unfair competition between licensed vendors and physical businesses. He called for the establishment of a fair and enforceable system to prevent vendors from encroaching on supermarket spaces and shifting legal responsibilities.

An expert warned that lifting the limit on street vending could have disastrous consequences, potentially overcrowding popular areas, squeezing sidewalks, and local businesses. He questioned why the city has not first tested the no-cap policy in individual busy commercial areas and pointed out that most supporters are unwilling to experiment with this high-risk approach in their own districts. Additionally, he criticized the city for its double standards toward vendors – strict penalties for truck drivers idling, yet allowing thousands of vendors to use noisy, polluting gas generators in close proximity to pedestrians all day, significantly impacting the environment and cityscape.

Several Chinese vendors from Flushing spoke, expressing their willingness to operate legally but highlighting the government’s failure to provide practical channels for obtaining permits, leading vendors into the dilemma of forced illegal operation.

Vendor Helen Fang suggested implementing a clear process similar to a driver’s license system, establishing a “permit issuance, violation, revocation” process to enable law-abiding vendors to operate legally and punish violators, freeing up spots for compliant waitlisted vendors.

Among the Chinese vendors who testified, some emphasized that vending is their sole means of livelihood, while others pointed out that they sell affordable and convenient goods, meeting the post-work consumption needs of laborers and bringing tangible convenience to city life. Some vendors questioned whether law enforcement actions were primarily based on store reports, leading to concerns of bias in favor of businesses and squeezing out competition for vendors. They also raised issues of frequent police crackdowns, multiple fines in a single day, theft of goods, and confiscation. Furthermore, some vendors criticized instances where ex-military personnel rented out licenses at high prices for profit, displacing genuine vendors seeking legal operation.

Many vendors stressed the economic vitality street vending brings to Flushing, attracting crowds and boosting local businesses, emphasizing that vendors are an indispensable part of the community. They believe that vendors are crucial for a diverse urban economy and vulnerable groups and call for the government to establish legal spaces for them to survive and thrive.