In the depths of the Pala Mountains in northern San Diego County, California, lies a mineral network with countless treasures, interwoven with a history that is both awe-inspiring and poignant.

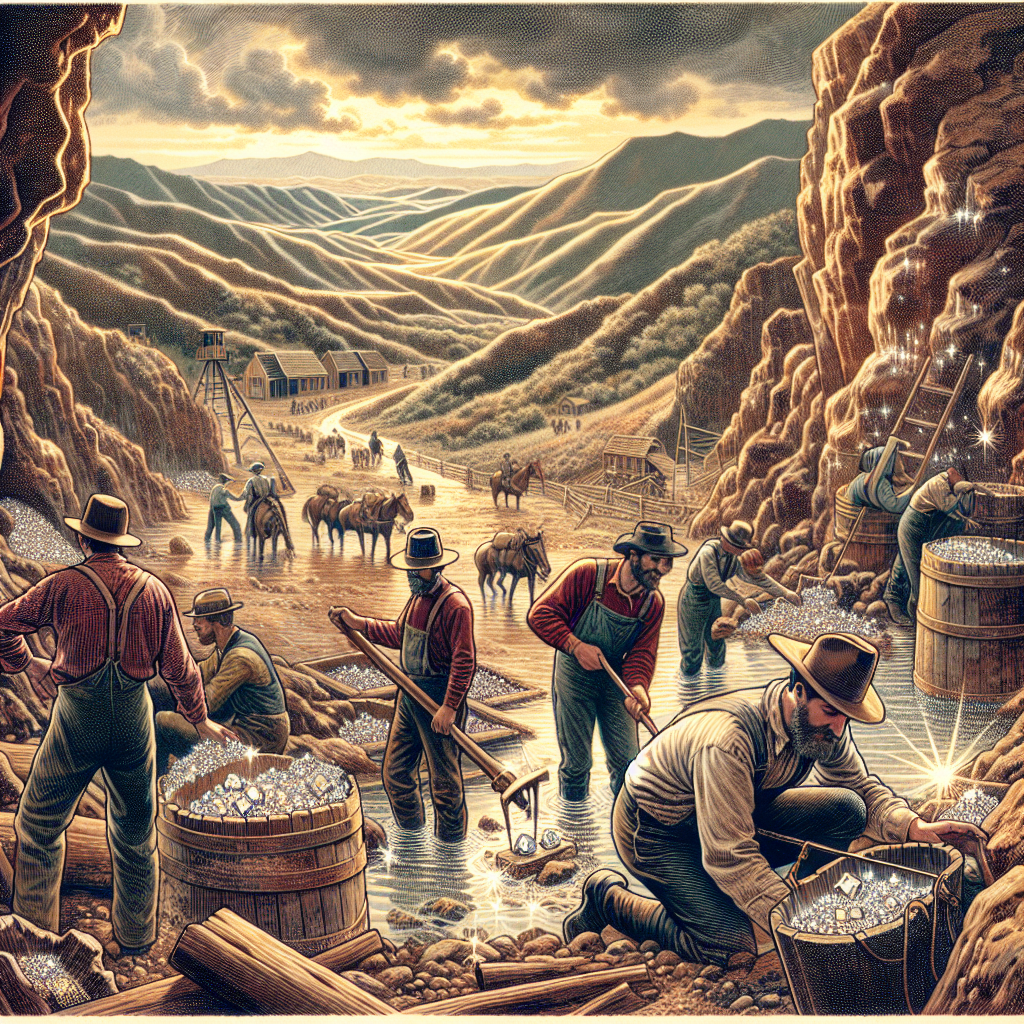

Over a hundred years ago, the “gem fever” that swept through the Pala region was much smaller in scale compared to the California Gold Rush of 1849, but it was equally rich and legendary in its own right.

According to a book published by Tiffany gemologist George Frederick Kunz in 1905, tourmaline was first discovered in 1872 on Thomas Mountain in Riverside County.

Tourmaline exhibits a rich and dazzling array of colors, often mistaken for precious gemstones like rubies, emeralds, or jade due to its intricate beauty and versatility.

Interestingly, it was Chinese laborers working in the mines who discovered the pink tourmaline. Their find captured the attention of Empress Dowager Cixi of the Qing Dynasty, who developed a deep fondness for the pink gemstone, forging a lasting connection with the mine.

Deep within the Stewart Mine in Pala, illuminated by headlamps, gem cutter and educator Blue Sheppard, along with his wife, gemologist Shannon Sheppard, are bringing this glorious history back to life within the purplish-pink gem-lined tunnels.

Sheppard describes the intersecting mine tunnel walls as being hailed by experts in the gem world as “one of the most beautiful mine tunnels in the world.” He acquired the mine in 1989 and began extracting gems the following year.

After the Gold Rush peaked in 1852, many Forty-Niners migrated south to San Diego County. While they didn’t find much gold, their quest for treasure yielded unexpected riches – strange purple rocks and pink and green crystals found in their gold pans.

Chinese laborers, who were extensively employed in constructing railroads and docks during the late 19th century, also played a significant role in mining lithium mica, primarily valued for its industrial application in lubricants during the peak of the Industrial Revolution.

With a surge of Chinese laborers arriving in California during that time, several were employed at the Pala mine specifically tasked with mining lithium ore.

During their work, some laborers stumbled upon brightly colored pink crystals. With the company’s permission, these workers ventured beyond the main lithium vein after laboring 10 to 12 hours a day, hoping for a fruitful outcome.

Samples of the pink stones, known as “long pink jade,” were sent back to China by some of these laborers. The news quickly reached the Qing Imperial Palace, piquing Empress Dowager Cixi’s interest in the pink tourmalines, leading to emissaries being dispatched to procure vast amounts of the pink gemstones from the Pala mines to bring back to China.

By the early 1890s, China had become the largest buyer of tourmaline, to the extent that the collapse of the Qing government in 1912 led to the collapse of the tourmaline trade.

However, the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 forced many Chinese laborers to leave the Pala region. The act, signed by US President Chester A. Arthur, aimed to exclude Chinese immigrants from American society.

Reflecting on that period, Sheppard remarked, “The Chinese laborers suffered persecution, and their commercial, mining rights, and property records were completely erased. It was a terrible catastrophe.”

Before their forced departure, Chinese laborers at the Pala mines deliberately sealed off the mine tunnels where they had dug up the pink tourmalines.

The Chinese Exclusion Act wasn’t repealed until 1943 during World War II, as part of efforts to secure China as an ally against Japan. In 2011 and 2012, the US Senate and House of Representatives unanimously condemned the act.

In 1970, the new owners of Stewart Mine decided to excavate tourmaline on the other side of the mountain. By then, the legend of the “Chinese tunnels” had almost become mythical, with Sheppard stating, “like Bigfoot or UFOs, many people no longer believed it truly existed.”

However, as miners blasted through rocks, they unexpectedly pierced the Chinese tunnels. Sheppard mused, “It was a gift from above.”

As the miners advanced along the tunnel, they stumbled upon a breathtaking treasure trove – naming it the “Bridal Chamber” because “it’s where the Earth delivers its treasures.”

Sheppard recalled how miners carefully continued to excavate beyond the “Bridal Chamber,” eventually entering a massive chamber filled with tourmaline.

The tourmaline veins in this area can stretch up to three feet wide, with gem pockets every five to ten feet containing countless tourmalines, morganites, lithium micas, and quartz crystals.

“Value of some gem pockets can reach up to half a million dollars, packed with tourmaline crystals in staggering quantities,” Sheppard said. “The discovery was world-shaking.”

He estimated that 30% to 95% of gem pockets in different parts of the mining area remain unexplored.

Tourmaline boasts a spectrum of colors richer than all other gemstones combined, attributed to its ability to absorb metals like iron, tin, chromium, manganese, creating unique color variations.

The word “tourmaline” originates from the Sinhala word “turmali,” meaning mixed colors or mixed stones, hence its nickname “rainbow gemstone.”

Unlike diamonds, rubies, emeralds that can be synthesized in laboratories, all tourmaline gemstones in the market are natural.

Sheppard, the founder of Gems of Pala, operated a gem shop and offered “visitor digging experiences” in the mining area for over 30 years. In recent years, he has shifted focus to online sales of gemstone bags and various gemstones.

He expressed, “In my 36 years at this mine, I’ve experienced countless stories. My love for this land is a serendipitous harmony and a deep-seated destiny buried deep in the earth. My only wish is that this passion continues, for future generations to cherish the gifts of tourmaline and lithium ores, precious offerings from nature.” #