In the past, astronomers and scientists believed that Mars was simply a planet with scarce water resources, covered with red sand and rocks. However, physicists in the United States analyzing data from the InSight spacecraft exploring Mars have discovered that there may be more water beneath the surface of Mars than previously thought.

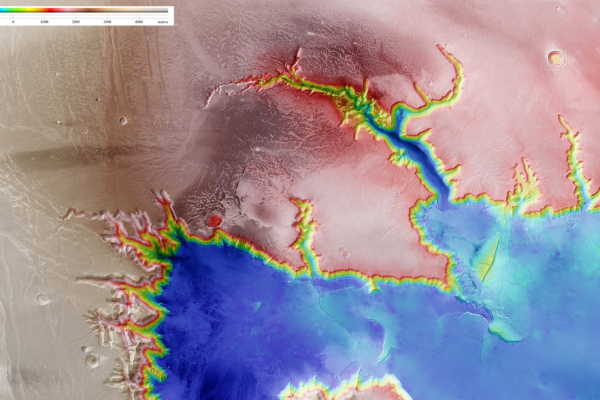

Based on evidence left on Mars, scientists have determined that Mars was once a wet environment with rivers, lakes, and oceans. But after Mars lost its atmosphere, it may have lost the ability to sustain liquid water, with the water potentially merging with minerals, being sealed deep underground in the form of ice or liquid, or even escaping into space.

However, scientists have yet to provide definitive evidence that all this water has turned into ice caps at the Martian poles. Some scientists suggest that the possibility of water being stored beneath the Martian surface or within its crust is greater, but this hypothesis lacks concrete proof.

Various countries have sent probes and landers to Mars multiple times to understand where the water on Mars has gone. This time, a research team from the University of California, Berkeley, and UC San Diego analyzed data collected by NASA’s InSight mission on Mars from 2018 to 2022.

Their analysis led them to believe that there may be a significant amount of water about 10 to 20 kilometers below the surface of Mars. However, they emphasize that drilling for underground water samples on Mars would pose significant challenges with current human technology.

The research findings were published on August 12 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, providing a detailed introduction and analysis of the study.

When InSight conducted exploration on Mars, it encountered earthquakes of around magnitude 5, meteor impacts, and rumblings from volcanic regions. These seismic activities helped InSight detect substances below the surface of Mars.

Seismic waves generated during earthquakes pass through rock, minerals, and cavities, producing different wavelength signals that allowed the InSight lander to gather a wealth of data related to the subsurface. Physicists analyzed this data to understand the internal structure of Mars and address questions about Mars’ geology and the whereabouts of ancient Martian oceans.

The UC Berkeley research team concluded that the material in the middle of Mars’ crust is largely composed of thin fissure basalts, filled with liquid water. The calculated amount of water is equivalent to a crust thickness of 1 to 2 kilometers on Mars, suggesting that Mars’ water content may be much larger than previously predicted ancient Martian oceans.

The experiment team stated that the existing data not only helps understand whether Martian crust contains significant water but also provides insights into the mineral composition of Mars’ crust.

UC Berkeley’s Professor of Earth and Planetary Science, Michael Manga, remarked that the mission far exceeded their expectations. He stated that by examining all the seismic data collected by InSight, they calculated the thickness of the crust, depth of the core, core composition, and even the temperature inside the core.

Assistant Professor of Planetary Science at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Vashan Wright, emphasized the importance of understanding Mars’ water cycle for grasping the evolution of Mars’ climate, surface, and interior. This knowledge is crucial to pinpointing the water on Mars and estimating its quantity.

Professor Manga added, “When we confirm the existence of a massive reservoir of liquid water on Mars, it provides us with a useful window into understanding the climate that may have existed then or could still exist.”

He continued, “Water is a vital necessity for known life, as seen in deep mines and ocean floors on Earth. We do not understand why this underground reservoir on Mars is not a habitable environment. While we have yet to find any evidence of life on Mars, at least we know it is a potential place to sustain life.”

The related research work was supported by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, the National Science Foundation, and the U.S. Office of Naval Research.