Nanjing Museum Controversy Over Ming Dynasty Painting “Spring in Jiangnan” Reignited

The whereabouts of the Ming Dynasty famous painting “Spring in Jiangnan” have once again sparked a debate about the loss of cultural relics at the Nanjing Museum. As historical records and various memories are pieced together, the event not only points to the identification and disposal procedures but also reveals a context spanning several decades: from the former director’s “dedicated protection” leading to wrongful death, privileged intervention in cultural relic management, to institutional flaws and distorted values, the prevalence of a “money-worship” culture reflects deep-rooted rifts within the Chinese cultural and museum system, and even within the CCP regime.

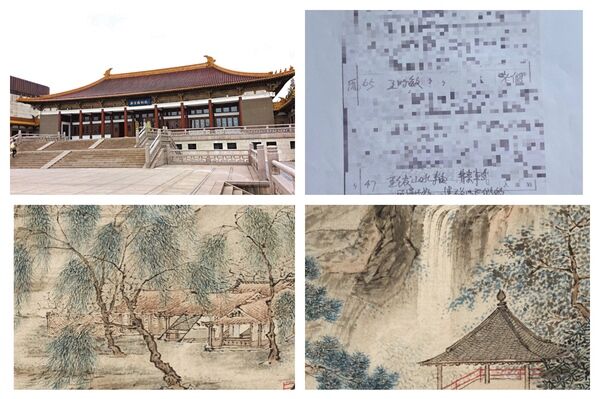

At the end of 2025, a suspected Ming Dynasty masterpiece by Qiu Ying, “Spring in Jiangnan,” appeared on the auction market, estimated to be worth about 88 million Chinese yuan. What garnered significant public attention and was repeatedly mentioned was the late former museum director, Yao Qian. This brought back to light an old case spanning several decades.

According to a post by the blog “Learn from History” on Tencent, Yao Qian entered the Nanjing Museum in 1954 and rose to the position of director. He was a professionally recognized leader in the cultural and museum sector for being knowledgeable and responsible. However, on November 8, 1984, under immense mental pressure, Yao Qian hanged himself in his office and passed away at the age of 58.

In 1985, after an investigation by relevant departments found accusations of “plagiarizing academic achievements” and “abusing power for personal gain” against him to be unfounded, he was exonerated, and an apology was published on the front page of the Guangming Daily.

Yao Qian (1926-1984), originally named Yao Xianchang, was a senior scholar in the cultural and museum sector. The blogger “Volcano Poems” described him as someone who treated the storage rooms at the museum as a battleground for thirty years, firmly believing in the principle of “preserving cultural artifacts with his life.”

Jiang Pinchao, a writer in the National Library of the United States, stated in an interview with Epoch Times that Yao Qian represented the conscience and backbone of intellectuals at that time, possessing the fervor to sacrifice his life in order to safeguard national cultural heritage.

He admitted that such conscientious intellectuals are becoming increasingly rare in contemporary times where the prevalent “money-driven” culture prevails.

The origins of the “Spring in Jiangnan” at the Nanjing Museum can be traced back to 1959. Documents show that in that year, the Pang family donated 137 calligraphy and paintings to the Nanjing Museum, including Qiu Ying’s “Spring in Jiangnan.”

However, decades later, descendants of the Pang family discovered that five paintings from the donation list had appeared in the auction market. One of them purportedly fetched over 80 million yuan. Upon inquiry by the family, the official response they received was that after “two expert appraisals,” the batch of paintings was determined to be forgeries and were disposed of according to the law due to lacking “preservation value.” As for the buyer, the internal circulation list only noted “customer.”

Member of the China Writers Association Wu Xuehua pointed out in a commentary article that this kind of operation constitutes a “perfect loop”: “If you are authentic, you are valuable; to turn you into money, one must first prove you are fake. Once deemed fake, I can then sell you legitimately.”

He bluntly stated that the so-called “distinguishing the real from the fake” has in some contexts transformed into a well-established “whitewashing mechanism”: experts sign off, processes comply, the item disappears, only to reappear at auctions after a few years.

The deep-rooted background of the “Yao Qian incident” had already emerged in the 1980s. Chinese Red Studies scholar Feng Qiyong (1924-2017) documented in his oral autobiography “Life Amidst Winds and Rain” a chapter titled “The Yao Qian Incident,” revealing that some “veteran comrades” in Jiangsu province habitually borrowed valuable calligraphy and paintings from the Nanjing Museum, with “borrowing without returning” even becoming common practice.

The article stated that according to the regulations, museum collections should not be lent to private individuals, but due to the borrowers’ identities as provincial committee leaders, Yao Qian “had no choice but to lend.” However, he was very meticulous, meticulously logging each borrowed cultural item and repeatedly chasing them up upon the expiration of the loan period. The failure to recover the items eventually led to discontent.

Yao Qian then fell into a trap, first anonymously reported for “issues with his lifestyle,” but no evidence was found, then accused of “plagiarizing academic achievements” and the criticism escalated in the media; on August 26 and 27, 1984, the Guangming Daily published several pieces directly criticizing him, causing enormous public pressure; finally, on November 8, 1984, Yao Qian hanged himself; and in 1985, he was exonerated and apologized to.

Jiang Pinchao analyzed that this exposed a fatal flaw in the system: professionals lack protection mechanisms and the authorization to reject power intervention; when faced with threats from “larger bureaucrats” and “interest groups,” once they uphold their principles, they may face media defamation, professional suppression, and even endanger their personal safety.

“Today, not many people would sacrifice their lives like Yao Qian,” he said, “It’s not the same era anymore.” Without protection mechanisms, professionals would face senseless sacrifices. “Who would be willing to give up their lives to protect the so-called national property?” he asked.

At a macro level, such events are closely linked to the overall social atmosphere. Many commentators see this as a key background for understanding the loss of cultural relics.

Wu Xuehua pointed out: “Back then, Yao Qian was forced to die because he wanted to ‘retrieve things’; now people are busy ‘sending things out’ to get rich.”

Jiang Pinchao further analyzed that this reversal is closely intertwined with the power structure of the CCP. He stated that these high-ranking officials wield excessive power, and cultural relics like “Spring in Jiangnan” are worth “nearly a hundred million” once auctioned, posing great temptations. Within the CCP system, officials are worried that “if they lose their position, they can’t be greedy anymore,” so “everyone is greedy.”

“In the past, intellectuals still had the backbone to serve the country and the people,” he said. “From Jiang Zemin to Xi Jinping, where are they for the common people? It’s all about money. They climb up with this mindset, how can they govern the country well? When those on top are corrupt, the whole ethos deteriorates.”

Human Rights Lawyer Alliance leader Wu Shaoping approached the issue from a historical institutional perspective. He told Epoch Times that the CCP verbally claims to protect cultural relics according to the law, but the actual operations have never changed: during the Cultural Revolution, open looting occurred, and now various means are used to “steal.” Once cultural relics are integrated into the “state-owned” system, the authority to appraise and dispose is highly centralized in the hands of power structures. In the absence of judicial independence and press freedom, things that are true can be called false, and those that are false can be declared true.

He illustrated with a real case from his hometown: An ancient temple built during the Tang Dynasty rumored to contain buried gold was sought out and the monks kidnapped for digging using metal detectors in the early 1990s; although the looters were caught, the ultimate fate of “a box of cultural relics” remains unknown, and the case reached a “dead end.”

In his view, these “dead ends” are the consequence of a malfunctioning power oversight. He questioned the official monopoly and manipulation of the “appraisal rights,” stating, “Everything is decided by them”; once cultural relics are declared “state-owned assets,” they might ultimately fall into the hands of “the most powerful individuals.”

He said that in cases like the “Spring in Jiangnan,” the path of “appraisal as fake-disposal-selling to an anonymous buyer” appears more feasible against the backdrop of societal norms and power structures.

Jiang Pinchao’s conclusion was clear: this is not just a question of individual morality but a “systemic issue.” Without changing the system, the loss of cultural relics “cannot be stopped”; even if the director is replaced, the next one may commit the same scandalous acts in different ways—today declaring it a forgery and selling it, tomorrow under a different pretext.

“It’s just a matter of degree, not a qualitative change,” he emphasized.

The history of the Nanjing Museum also serves as a testament to the “systemic issues” of the CCP. According to the blogger “Listening to the Heart Hall” on NetEase, the first museum director, Ceng Zhaoyun, devoted her life to the cultural and archaeological field. She was the great-granddaughter of Zeng Guofan and tragically ended her life by jumping from the Linggu Tower in Nanjing on December 22, 1964, at the age of 55, leaving a note saying, “Today’s jump has nothing to do with the driver”; the second director, Yao Qian, died an unwarranted death on November 8, 1984, at the age of 58, and was exonerated in August 1985.

Spanning twenty years, both lives ended in the political environment, mental stress, and corruption of power structures under the CCP regime.

Commentators generally agree that a painting like “Spring in Jiangnan” donated to the Nanjing Museum in 1959, the tragedies of the two directors in 1964 and 1984, the “fake disposal” in the 1990s, and its reappearance in 2025 ultimately point not to market and appraisal issues but the irreversible systemic dilemmas within the CCP system.